An interesting podcast about Claude Shannon that doesn’t talk about Nyquist.

Category: Digital Audio

Loudspeaker Crossovers: Part 16

This posting is just wrapping up the series. No more plots… I promise.

Of course, this entire series has focused the “greatest hits” of the crossover club which is a limited number of crossover types. There are many other options that I haven’t talked about, but my point was not to explain how to choose and design a crossover for a loudspeaker for the DIY’er. It was to

- give a primer on some of the things to consider when implementing a crossover

- instil instinctive suspicion and doubt when you read an advertisement (or a comment on the Internet) that says something like “this loudspeaker is good (or bad) because it has THIS kind of crossover.”

There are plenty of things that I didn’t (and won’t) talk about, such as:

- Crossovers for loudspeakers with more than two outputs

- Other crossover designs. For example, as a start, search for:

- Malcom Hawksford Asymmetrical Crossover

- Malcom Hawksford discussion of stochastic crossovers associated with DMLs

- Linkwitz’s page on crossover design

- “Constant-Voltage Crossover Network Design” by Richard Small

On thing that I intentionally avoided was crossover designs that use filters with extremely high orders, sometimes called “brick wall” crossovers. On paper, they avoid the possible issues with a signal in a given frequency band coming from two sources (e.g. a woofer and a tweeter), so if you ONLY consider them from this perspective, they’re a good idea. However, in my opinion, this is outweighed by the facts that you will probably get a discontinuity in the power response (unless the two drivers have identical three-dimensional radiation patterns at the crossover frequency) AND you will probably have a complete mess in the time domain. Bonkers-order filters aren’t free. (If you clicked on the link to Linkwitz’s page, above and just taken a quick glance, then you’ve probably read the statement at the top of the page that says “The sum of acoustic lowpass and highpass outputs must have allpass behavior without high Q peaks in the group delay.” One way to look at the group delay of a filter is to look at the slope of the phase response. If you make a crossover with really high-order filters, then one of the artefacts will be a high slope in the phase response around the crossover frequency.)

One other thing that I have not mentioned is the incorrect naming that is often associated with crossovers and filters in general. Many people say “FIR Filter” (Finite Impulse Response) when they actually mean “Linear phase filter”. It’s important to remember that you can’t have a linear phase filter without an FIR filter implementation, but certainly not all FIR filters are linear phase. (Weirdly, a linear phase filter does, in fact, have an infinite impulse response, both forwards and backwards in time… But that’s a description of the filter’s response and not how it would be implemented in a DSP-based signal flow.) This incorrect usage drives me nuts. (Then again, many things like this do. For example, I get annoyed when HR people draw a triangle on a whiteboard and call it a pyramid. You never know what’s going to set me off on a pedantic rant about nomenclature.)

The other thing that I didn’t talk about was another way to look at a Butterworth two-way crossover, in which you see it as lacking a component in the s-domain (using Laplace analysis), which is the reason its sum has an allpass characteristic. If you add the missing component (for example, using a third loudspeaker driver), then the allpass behaviour disappears. This is the concept behind Bang & OIufsen’s “Uni-phase” series of loudspeakers in the 1970s and 1980s. If you want to learn more about this, I’ve already written about it here, and Erik Bækgaard’s original paper from 1977 describing the idea more fully can be found here.

Finally, hopefully, you won’t come away from all of this with a conclusion that one crossover is the winner. A crossover is just one component in a long series- and parallel-chain of components that make up a loudspeaker. Changing any of the other components may require making a different decision about another. And, in order to make that decision, you can’t just consider the on-axis response (unless you live alone in an anechoic chamber (or outdoors…). You also need to think about things like

- the off-axis responses

- the power response

- the phase response

- the time response

and maybe also - the implications on latency

- your required signal processing power (e.g. in MIPS)

- maybe some other stuff if you have checked all those boxes.

On the other hand, after all this, you should also know that you can’t just implement a crossover ignoring everything else in the chain, and think that it’ll just work. It won’t.

Loudspeaker Crossovers: Part 15

This will be another short one.

Part 14 showed the power responses of a theoretical loudspeaker made with two point-sources using a linear-phase crossover using the method that I explained in Part 7.

In Part 11, I showed the power responses when the loudspeaker is made with real drivers in a real enclosure.

This posting shows the same as Part 11, except that I’ve implemented the crossover (at 1 kHz) using linear phase filters (again, with a really long window to avoid any discussion) instead of minimum phase filters.

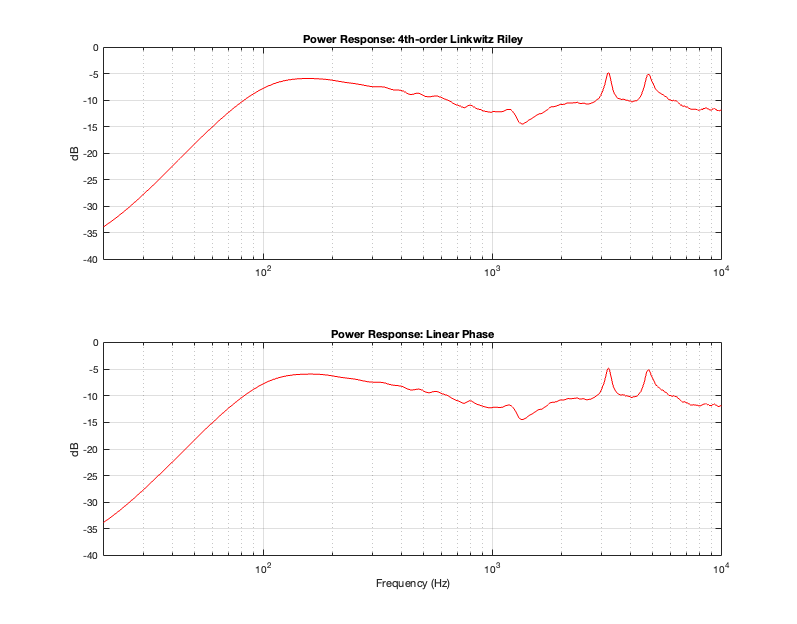

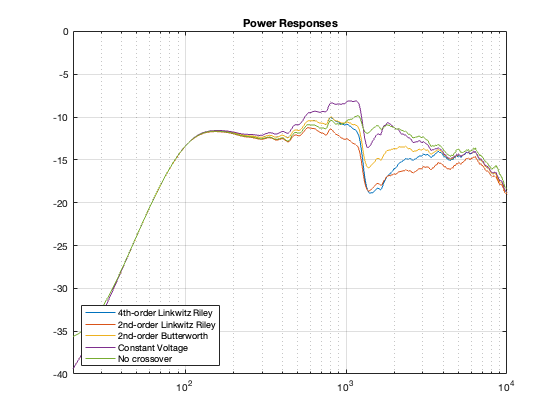

Figure 15.1 shows the real-world power responses of an actual two-way loudspeaker using two crossover strategies. (The top plot was already shown in Part 11.)

Based on the conclusions from Part 14, it should not come as a surprise that a linear phase crossover will result in the same power response as a 4th-order Linkwitz Riley crossover. The only reason I’m showing this here is to prove that the earlier conclusion based on a theoretical simulation holds true in real life.

One important conclusion to make at this point is to realise that a loudspeaker that is implemented with a 4th-order Linkwitz Riley crossover and the same loudspeaker implemented with a linear phase crossover will have identical magnitude responses (in any direction – not just on-axis) and identical power responses. However, they will have different phase responses (in any chosen direction) and different temporal responses (aka impulse responses).

Loudspeaker Crossovers: Part 14

This will be a short one.

In Part 7, I showed the power responses of three loudspeakers made with point-source (and therefore perfectly omnidirectional at all frequencies, which also means that they have the same response in all direction) drivers.

In that posting, I calculated the power response for a loudspeaker made of two loudspeaker drivers, floating in space, with the assumption that both drivers are point-sources, and that they do not live in an enclosure that has any acoustical effects. I also calculated the responses for 3 different distances between the drivers, which were chosen as a function of the crossover frequency’s wavelength.

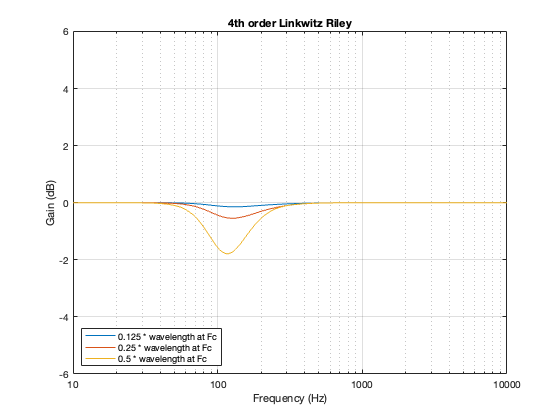

One of the crossover types whose power responses that I showed was the 4th-order Linkwitz Riley. The plots that I showed back then for that crossover type is reproduced here in Figure 14.1.

As I said, the details of how I calculated these power responses is detailed in Part 7.

I calculated the power responses for a similar loudspeaker, using a linear phase crossover (with a really long window to avoid any discussion about this…) and with the same crossover frequency of 100 Hz and the same distances between the “drivers”. These power responses are shown below in Figure 14.2.

If you look at Figures 14.1 and 14.2 you could be forgiven for thinking that they look VERY similar. In fact, they’re essentially identical. This is because the 0º difference in phase caused by the linear phase crossover is the same as a 360º difference in phase caused by the 4th order Linkwitz Riley.

In other words, the message of this posting is that the power responses of a loudspeaker that has been implemented with a 4th order Linkwitz Riley crossover and the same loudspeaker with a linear phase crossover will have the same power responses, assuming that all other aspects of the loudspeaker are the same.

Loudspeaker Crossovers: Part 13

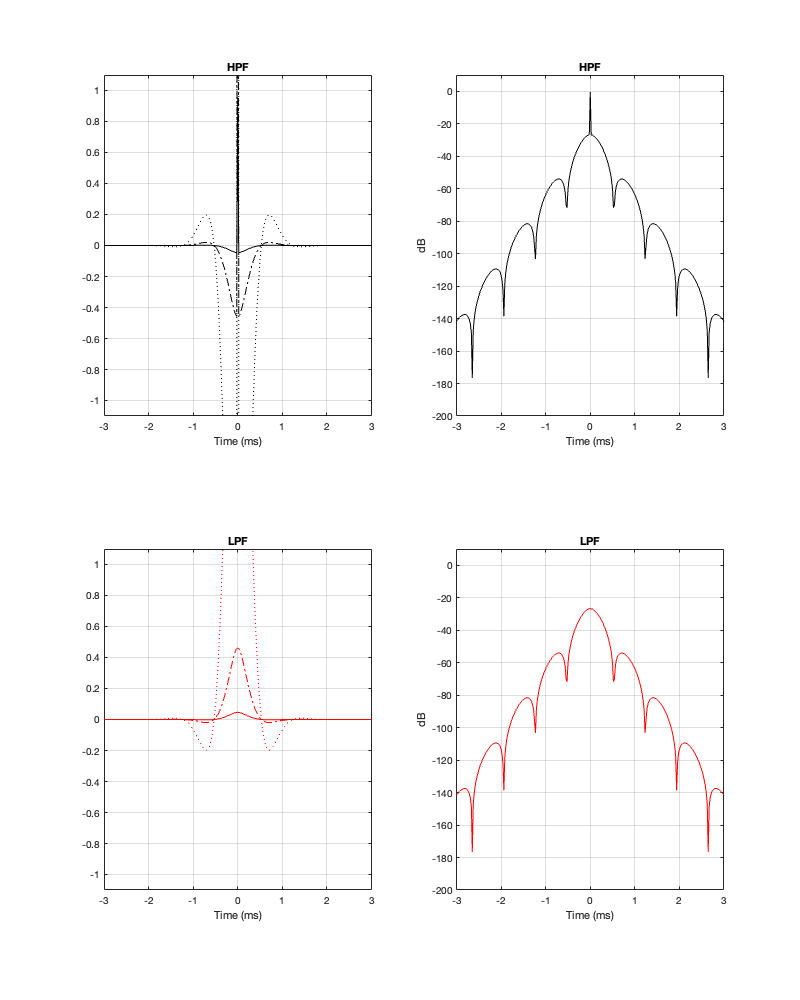

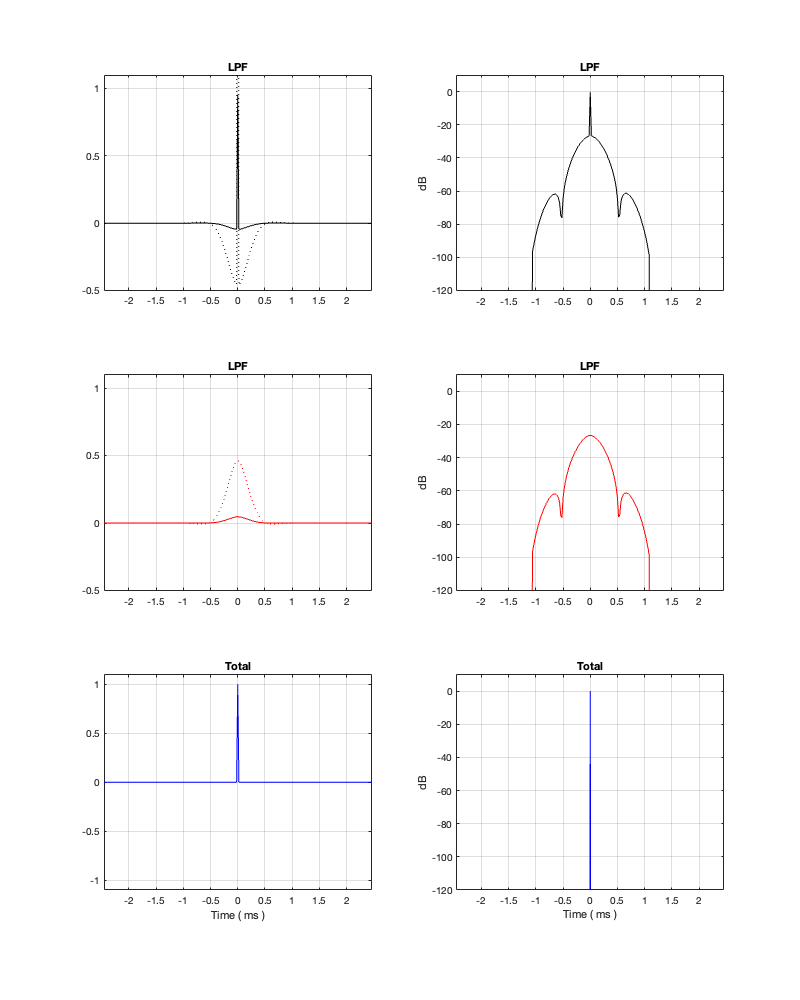

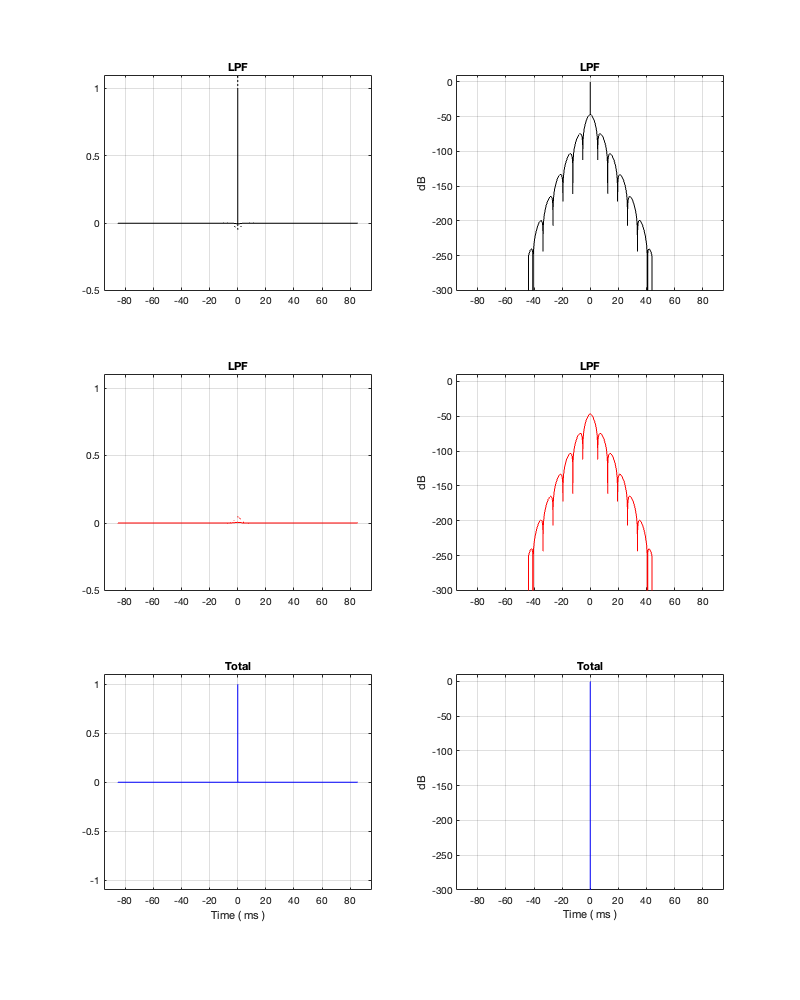

In the previous posting, I showed the frequency responses and impulse responses of the outputs of a crossover based on a linear phase filter strategy. One thing that can be seen in the impulse response plots in Figure 12.5 is that it never reaches a value of 0. It rings both backwards and forwards in time forever. However, this is not practical, since we don’t want to wait until the end of time to hear the output of our loudspeaker.

So, normally, we have to make a pragmatic choice about how long we’re willing to wait for the crossover filter’s to deliver an output. There are various ways to make this decision, but ultimately, we’re trying to balance the “error” in the responses of the crossover’s outputs with how long an input/output latency we’re willing to put up with. (We might also need to think about computational issues like how many calculations have to be done when you use a REALLY long filter, but I’m going to pretend that this is not an issue for this posting.)

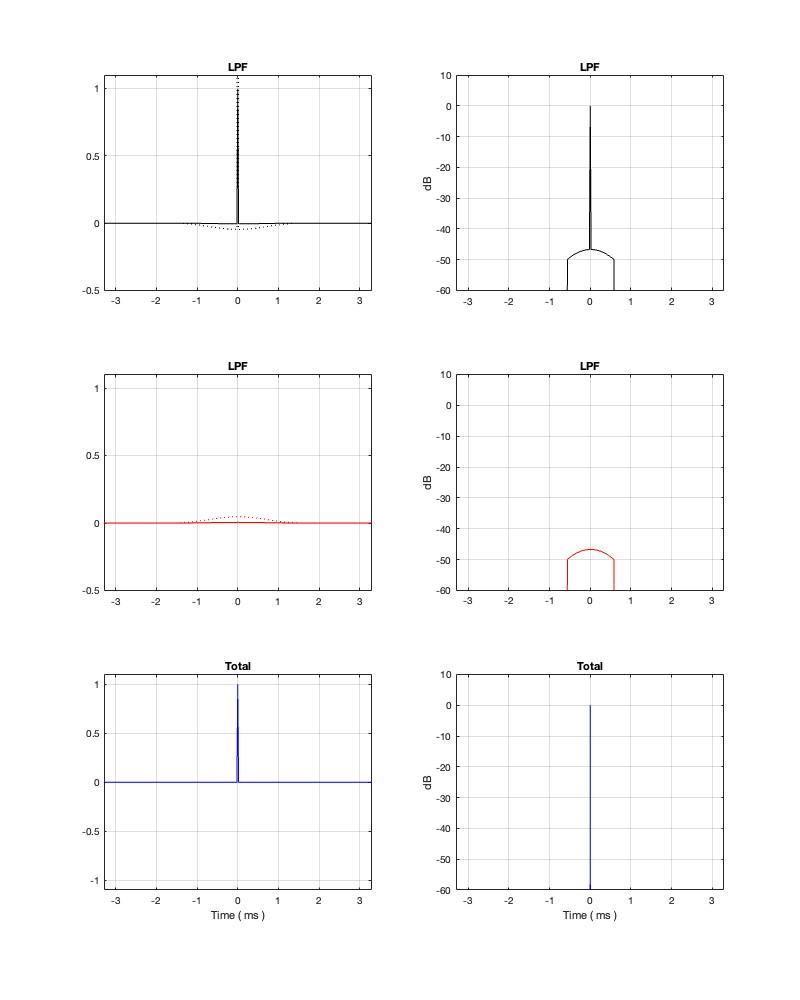

It’s difficult to see from a linear plot of the impulse responses of the two filters, but the peak is in the middle, at Time = 0 ms. Extending outwards, both backwards and forwards in time, the impulse responses oscillates back and forth across the 0-amplitude line. This oscillation is easier to see when it’s plotted in decibels, but then you can’t see whether the linear value is positive or negative. So, it helps to look at both to get an idea of what’s happening.

One thing that might not be immediately obvious is that, apart from the big spike at Time = 0 ms on the high-pass filter response, the outputs of the two filters are identical in amplitude, but opposite in polarity. In other words, they are symmetrical. This makes sense when you consider that, by adding them together, the total result is a single spike at Time = 0 and an amplitude of 0 at all other times. In other other words, the outputs of the two filters “cancel each other out” at all times except Time = 0.

This is a little weird if you think of it as the tweeter cancelling the woofer – but you consider that it’s doing it in time, at very low levels, then it might make more intuitive sense.

What happens if you don’t want to wait too long to get the output? In other words, if we shorten the impulse response around the central spike? This is a technique that is called “windowing” where you slice a window of time out of the middle of the impulse response and use only that.

There are a number of ways to do this. We could just say “everything up to 1 ms before the spike and everything after 1 ms after the spike, we just convert to silence”. This is the simplest way to do it, but it’s also the dumbest.

A smarter way is to look at the impulse response shown above, and fade into the spike and then fade back out again. Then you just decide on the shape of the fade and its length. It could be a straight line, or it could be something fancy.

I’ve written a lot about windowing in another posting a long time ago. If you want to learn about this topic, you could start there, or any book or website that talks about time-domain processing and analysis of audio signals. I won’t explain windowing in this posting. It’ll just get too long…

For all of the analyses below I did the following:

- Choose a crossover frequency

- Implement the crossover using linear phase filters

- Decide on a threshold in level (in dB below the spike at the input) to find out how long a window in time I’m going to use

- Apply a Hann window to the filters’ impulse responses with the length that I found above

- Show the magnitude and phase responses of the individual outputs as well as the summed total

Another way to do this would be to just decide on the length of the windowing (and find out the threshold of the level, below which you’re cutting the signal) and see what happens. Either way, you get a deviation in the response, you’re just setting a different parameter.

Fc = 1 kHz

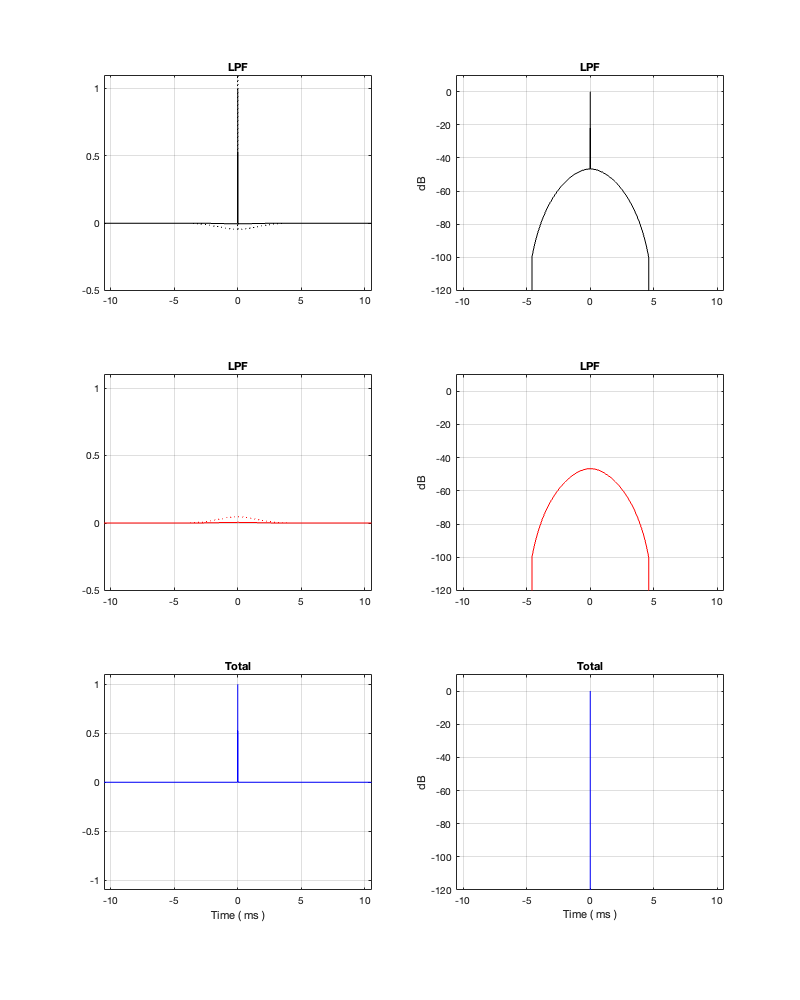

Let’s start with a crossover frequency of 1 kHz. If I say that I want to extend the impulse response very far down in level, I’ll wind up getting a very accurate filter response (in other words, I’ll get what I expect), but it’ll have a long input/output latency (which is half of the total windowing time).

Minimum Latency = 5.44 ms

Hopefully, comparing the plot in Figure 13.1 and 13.2 helps to clarify the explanation above. Essentially, the plots in those two figures show the same thing. However, you can see in Figure 13.2 that I’ve cut off the impulse response once it drops below -250 dB.

The effect of doing this windowing can be seen in Figure 13.3 where you can see that the roll-off for the tweeter doesn’t keep going down in level as you drop in frequency. This is because the lower the frequency you want to filter, the longer the filter’s impulse response has to be.

Notice, however, that, despite the fact that the two magnitude responses in the top of Figure 13.3 aren’t exactly what you’re expect, the responses of the summed total are what you’d expect. This will become a familiar theme as we continue.

If we raise the threshold, we’ll shorten the impulse response, which means that we shorten the latency, and we deviate from the expected responses.

Minimum Latency = 1.23 ms

Notice in Figure 13.5 that, although the two crossover outputs have very different magnitude responses from 13.3, the total sum still works. Intuitively, this actually makes sense when you look at the impulse responses, since they still cancel each other – they’re just identical but opposite (except for the spike in the tweeter).

Of course, since the filter is now shorter in time, we get a lot more low-frequency output from the tweeter.

Minimum Latency = 0.46 ms

Notice in Figures 13.6 and 13.7 that, with a threshold of -50 dB, our latency can be under 0.5 ms. However, we will be expecting a lot of level out of the tweeter at low frequencies, which might be unhealthy for it if we turn up the volume.

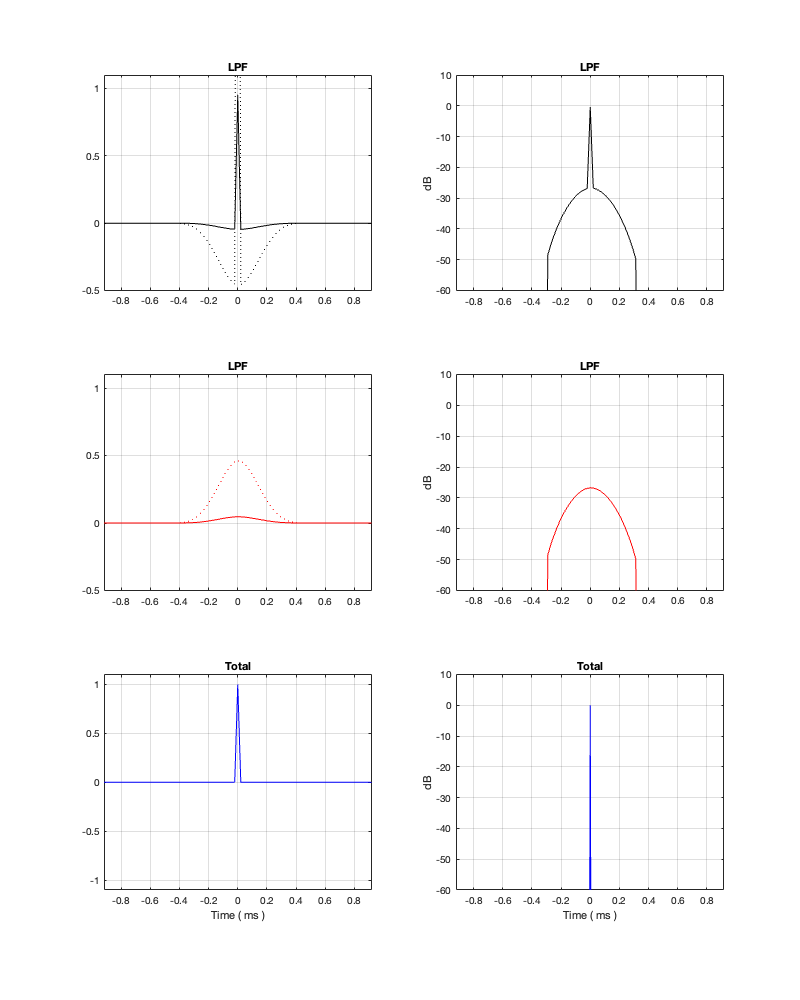

Fc = 100 Hz

Now let’s repeat the process with a 100 Hz crossover to see what happens.

Minimum Latency = 47.58 ms

Notice that, in order to implement a threshold of -250 dB, we need at least about 47 ms of latency, which is probably outside acceptable limits for lip synch with video. It’s certainly far too long to be used in a loudspeaker for live sound, since you’ll hear and echo-echo all the time-time.

Minimum Latency = 5.27 ms

Notice that, by changing to a threshold of -100 dB, we’ve dropped our latency requirement significantly – down to just over 5 ms. However, don’t trust everything you see there. This crossover probably won’t behave nicely… If we change the threshold to -50 dB, you can see where we’re headed, and why I am highly suspicious of the -100 dB filters…

Minimum Latency = 1.65 ms

Obviously, that filter isn’t going to give you what you want – although it’ll give it to you quickly… (Editorial comment: It’s like current AI: it’s the fastest way to get the wrong answer…)

Wrapping up for now

Like I said above, regardless of how much I shorten these impulse responses, the responses of the summed outputs look good. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the crossover will work well, as should be evident by looking at the responses of the individual outputs.

In addition, it should be evident that, in order to implement a linear phase crossover that behaves well, you will incur a latency that may not be acceptable, depending on the crossover frequency and your requirements. Then again, if you don’t care about latency, you might start requiring a lot of computational power to implement it.

Like any aspect of crossover choice and design, there are multiple parameters to play with…

In the next posting, we’ll take a look at the implications of a linear phase crossover on the three-dimensional power response.

Loudspeaker Crossovers: Part 12

Up to now in this series, we’ve looked at 4 different types of crossover designs:

- 4th-order Linkwitz Riley

- 2nd-order Linkwitz Riley

- 2nd-order Butterworth

- One version of a Constant Voltage design

These have been interesting because they’re popular designs, and they are implementable using either analogue circuitry or digital signal processing (DSP). So, everything I’ve said so far is independent of whether the processing is analogue or digital. This is even true of all of those equalisers I applied to the two loudspeaker drivers to force them to be flat. Those are easiest to implement with DSP, but I didn’t do anything there that can’t be done with resistors, capacitors, and inductors.

But, the original question was

In passive crossovers, many are phase incoherent,

meaning that the phase shift of one frequency will be different than another frequency.

Do you agree? Am curious how this is dealt with in the active crossover’s of B&O products?

Hopefully, it’s obvious that the answer to the first question is “yes” – sort of… Passive crossovers are not “phase incoherent” – but they do have an effect on the phase response. As I’ve shown, you can think of the end result of a crossover implemented with minimum phase filters as an allpass filter. So there is an effect on the phase response of the loudspeaker. (Yes, the on-axis response of a Constant Phase crossover can result in a flat phase response, so that one might be an exception.)

However, if we leave analogue signal processing behind and go forwards limited to digital signal processing, then we have another option: linear phase filters.

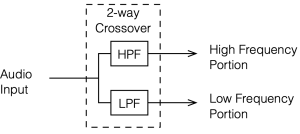

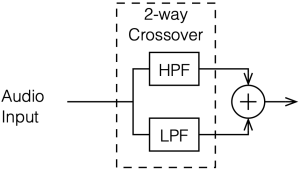

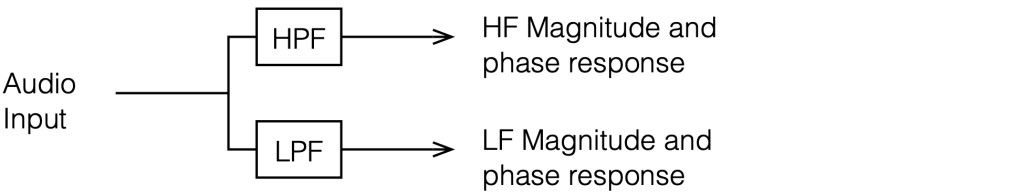

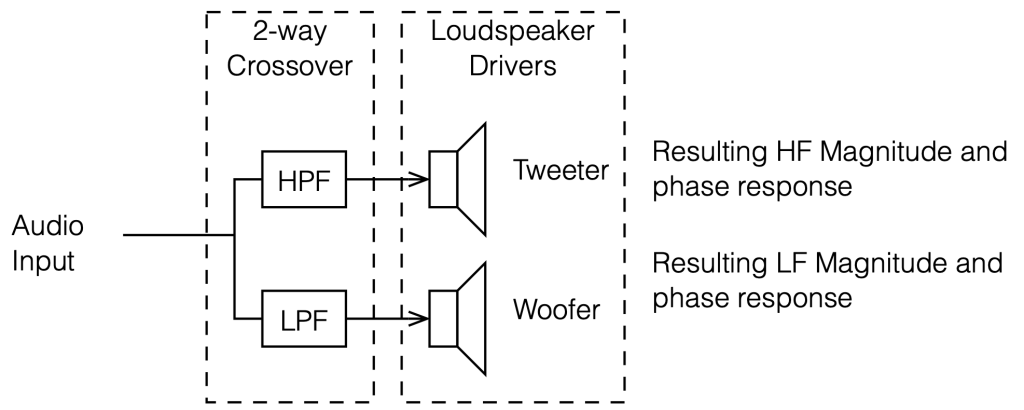

To start, let’s look at our original, simplified method of analysing a crossover, using the block diagrams shown in figures 12.1 and 12.2

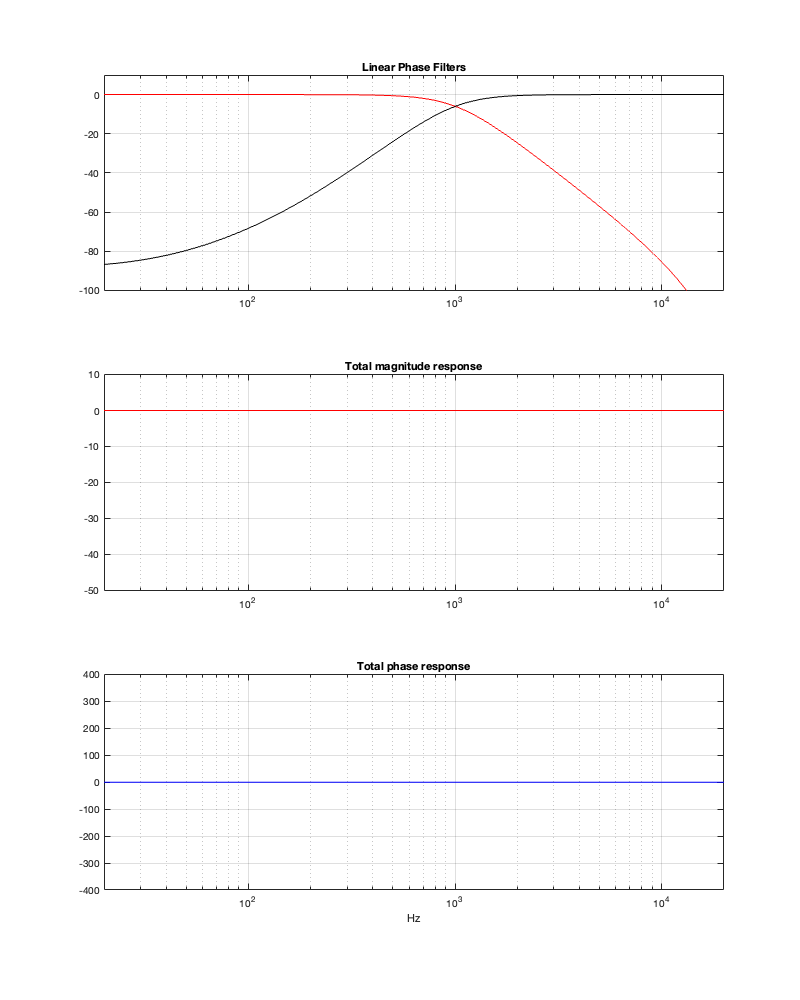

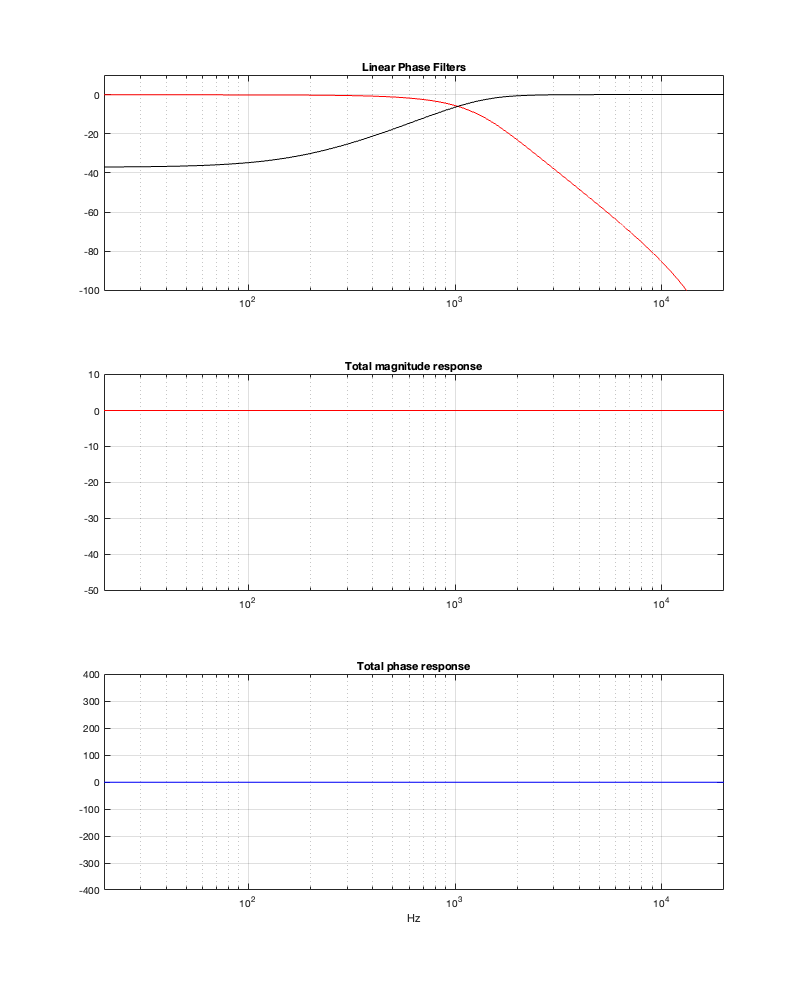

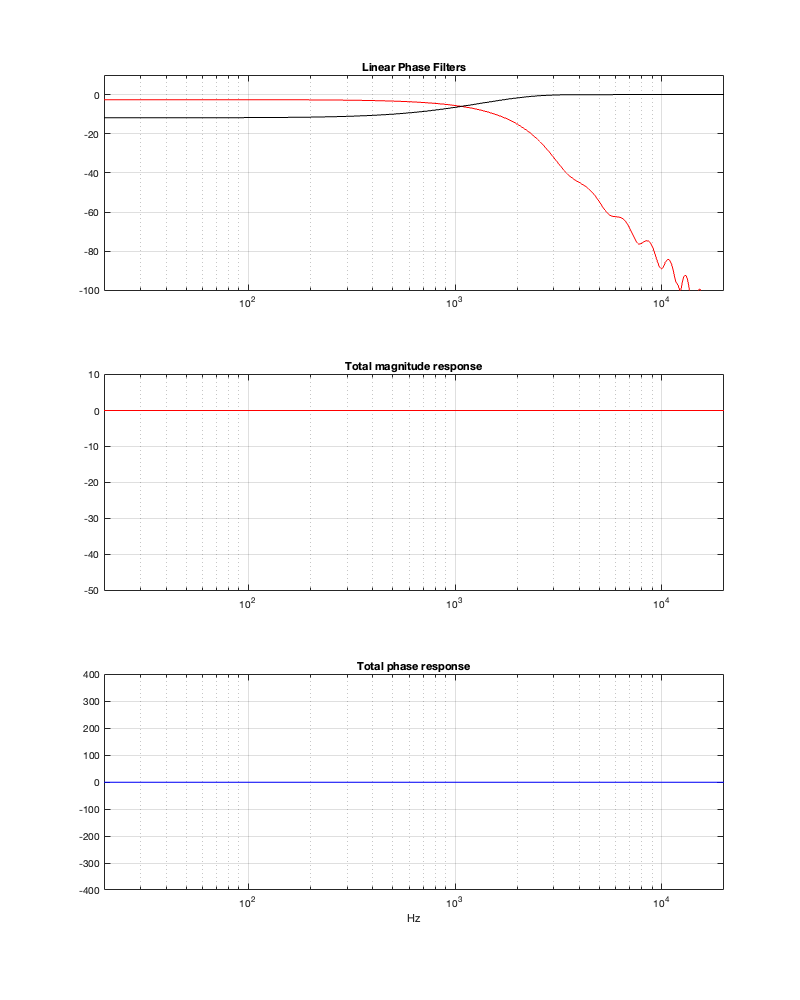

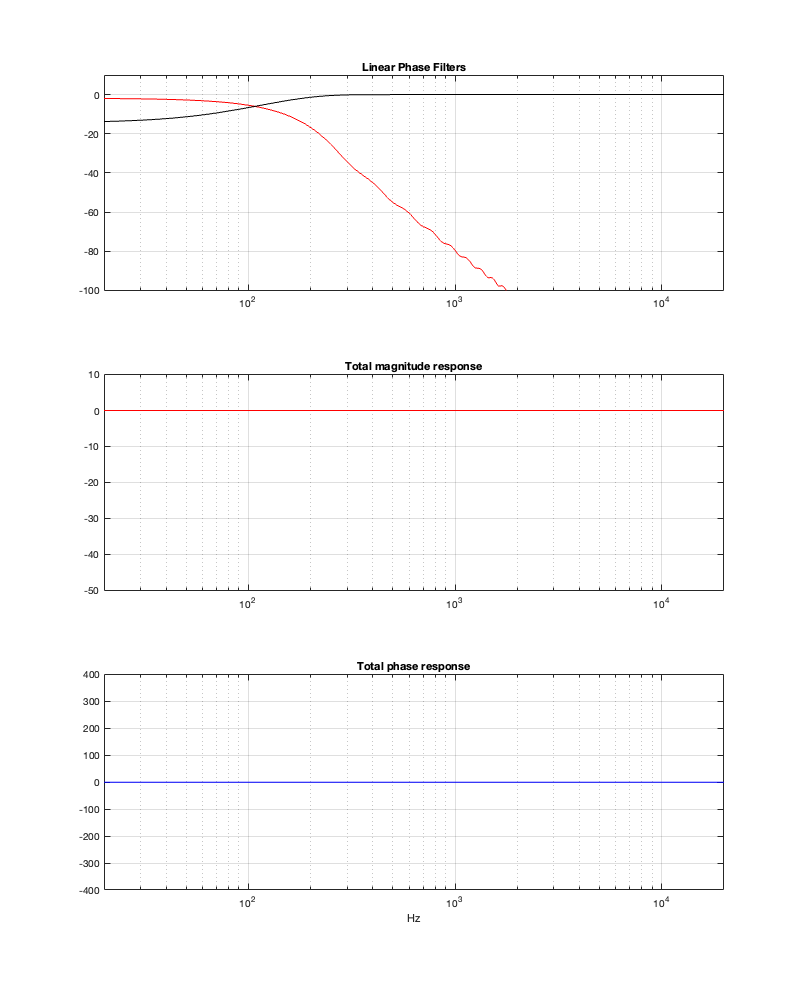

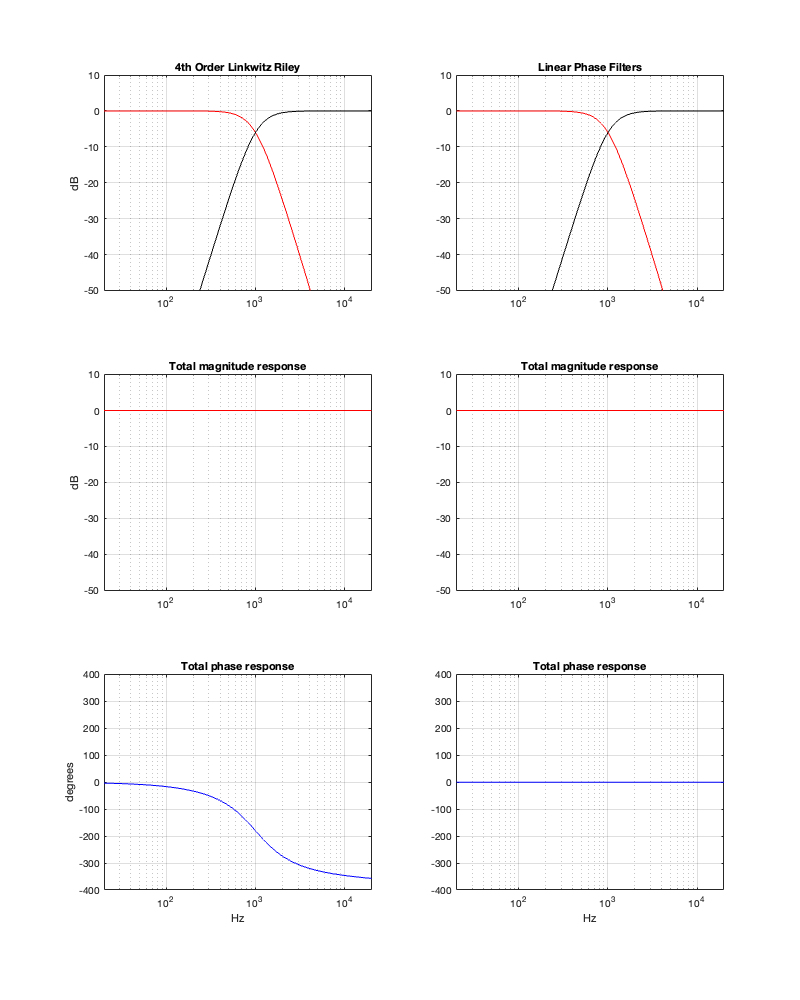

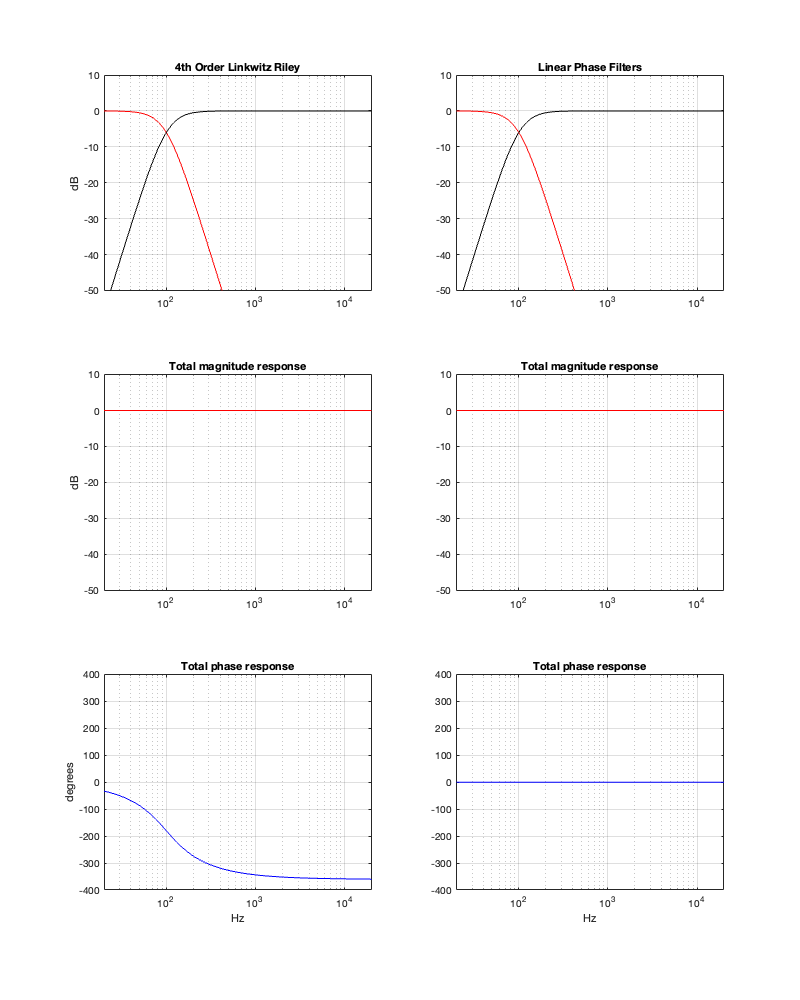

If we use this signal flow and create two crossovers at 1 kHz, one with a 4th-order Linkwitz Riley design (which I’ve already shown) and one with linear phase filters, the responses will look like the ones shown below in Figure 12.3

Looking at the magnitude responses, you can see that these two filter designs are identical. However, the phase responses of their total outputs are not. The Linkwitz Riley design behaves like a minimum phase allpass filter, whereas the linear phase design does not.

So, this proves that a linear phase crossover is better, right? Not so fast… We’re not done yet…

Time response

The plots above show the frequency responses (“frequency response” is the combination of the magnitude response and the phase response) of the two designs. However, there is another way to look at the response of a system like a crossover, and that is to analyse how it behaves in time.

If we create a signal that is complete silence, and then a single one-sample-long “click”, we have something called an “impulse”. If we then send that into an audio system (like a crossover, for example), then we can see how it behaves in time – its temporal response. Since this method shows us how the system responds when you send an impulse through it, we call it the “impulse response” of the system.

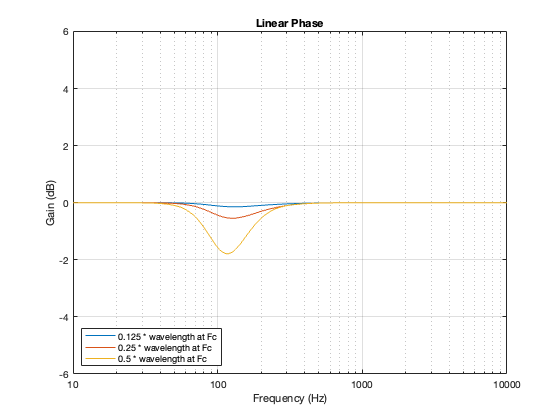

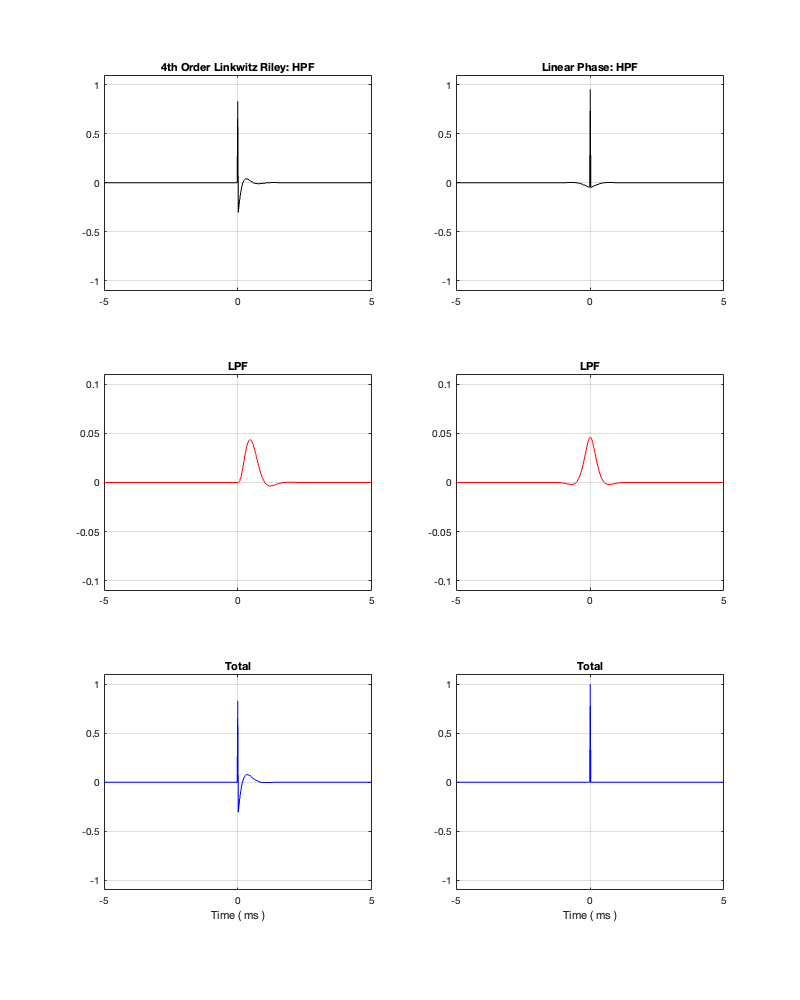

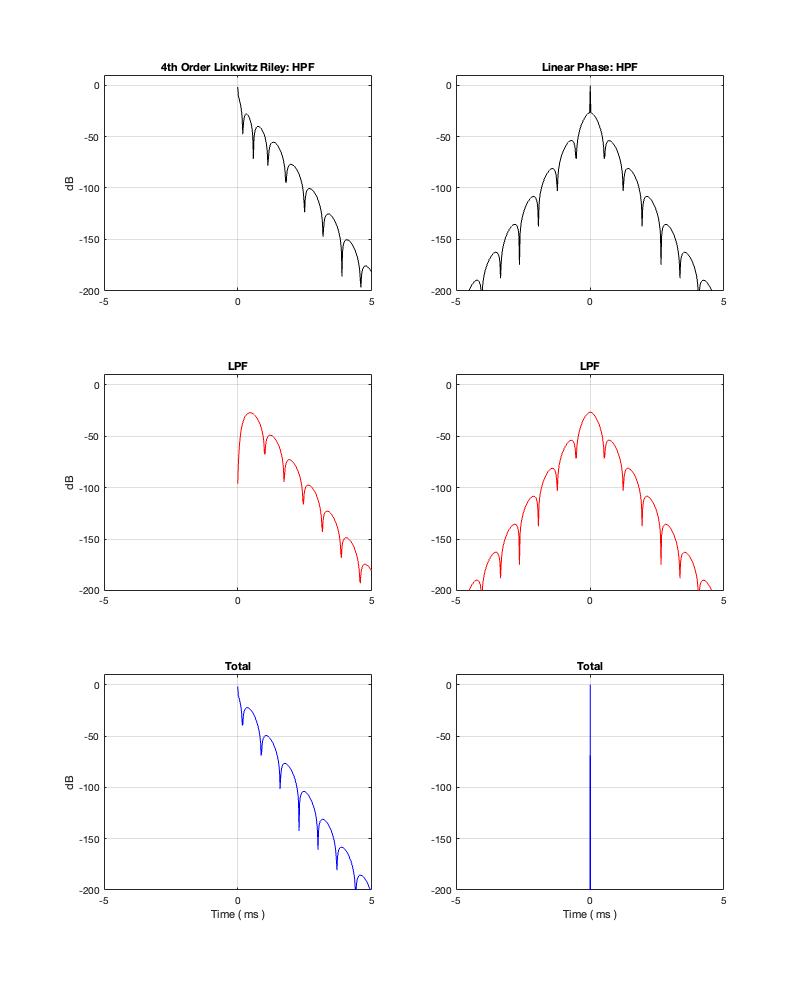

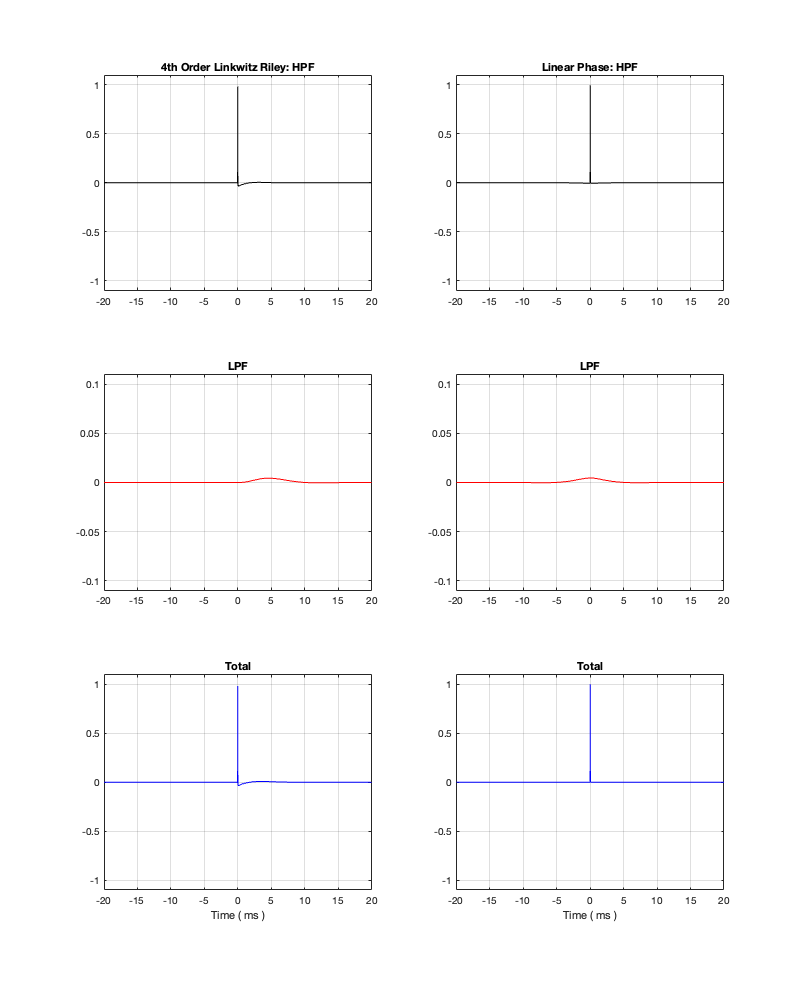

If we measure the impulse responses of our two 1 kHz crossovers, we get the results shown below in Figure 12.4.

As can be seen in the impulse response plots for the Linkwitz Riley crossover, until the impulse arrives at the input of the filter, the output of the filters are silence. This is the flat line with a constant amplitude of 0 from -5 ms to 0 ms. Then, at time = 0 ms, the impulse hits the input of the crossover, and something happens. The output of the high-pass filter spikes, and the output of the low-pass filter slowly (relatively speaking) starts ramping up. The combined output of the two filters, shown in blue, shows that the output is not a single-sample impulse. It has the characteristic shape of the impulse response of an all-pass filter.

The impulse responses of the high-pass and low-pass outputs of the linear phase crossover are similar-ish… but they have one characteristic that is VERY different. They have an output on the left side of time = 0 ms. One way to look at this is to say that they output a signal before the crossover gets something at its input. This is, of course, impossible: linear phase filters are not time machines.

So, how does this happen? By including a delay in the signal flow. In order to make a linear phase filter, you have to include a delay that starts is as long as is necessary to look after the stuff that you need to do to the signal before that big spike hits. So, if you want to use a linear-phase filter, then the “price” is that the output is going to be late.

How late? That’s up to you, since it’s a combination of the filter’s frequency and how accurate and precise you want the filter to be. One way to consider this is to look at the plots in Figure 12.4 on a decibel scale. This is shown in Figure 12.5.

Let’s say, for example, that you have this crossover at 1 kHz and you want to have an impulse response that is accurate down to -100 dB. Looking at HPF and LPF impulse responses for the linear phase crossover, we can see that they drop below -100 dB at about ± 2.4 ms. This means that, if you decide that your threshold of acceptability is about -100 dB (which is pretty good…) then, for a 1 kHz linear phase crossover, you’ll have to include a 2.4 ms delay in your signal path to implement it.

Of course, if you are more picky – say, you want to go down to -200 dB instead, then you’ll have to wait about 4.8 ms (check where the red and black lines get 200 dB down on the left side of the plots.

Notice that I said above that this amount of time – the delay (or as we normally call it: the loudspeakers input-output latency) is also dependent on the frequency of the filters.

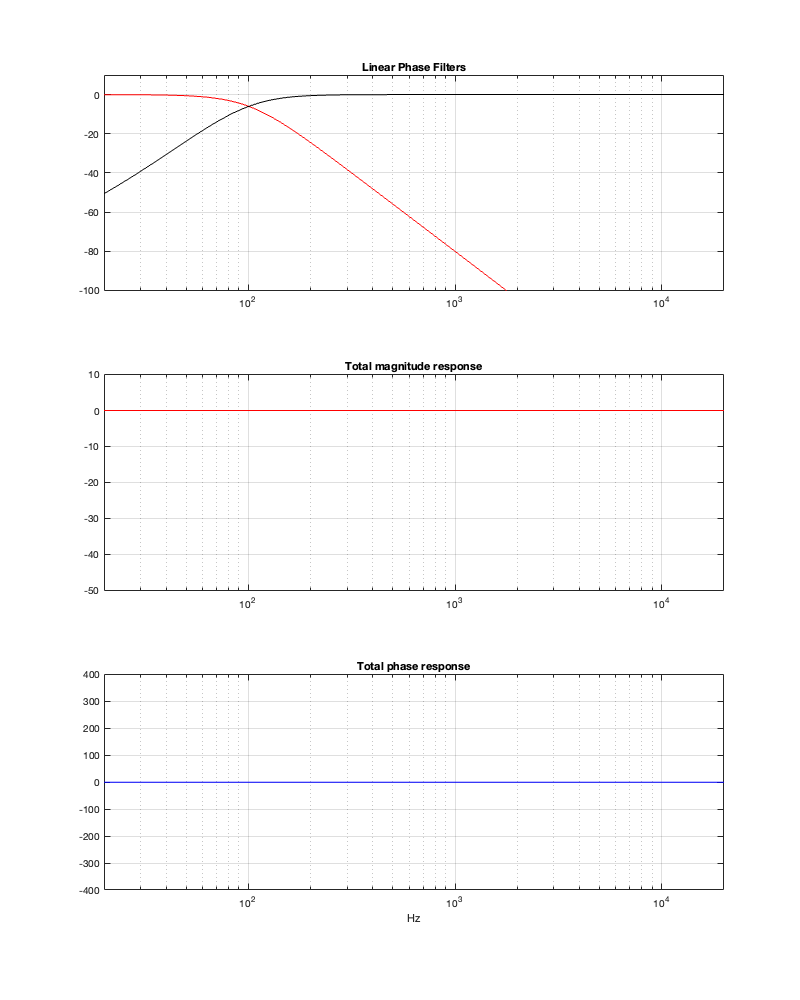

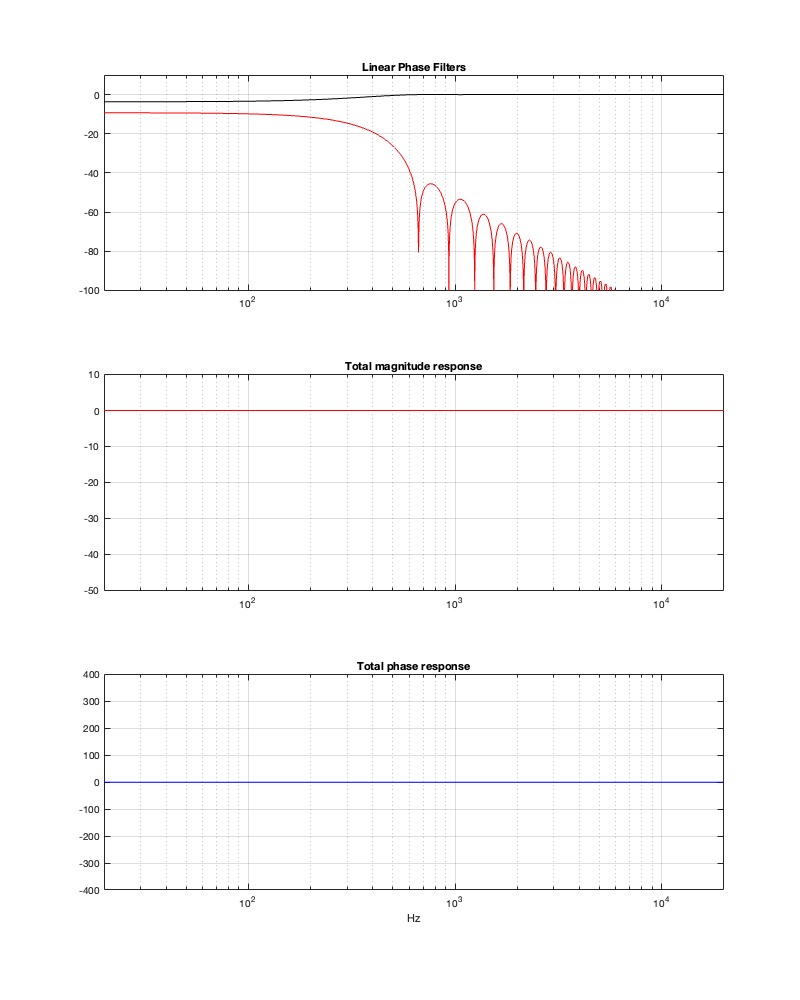

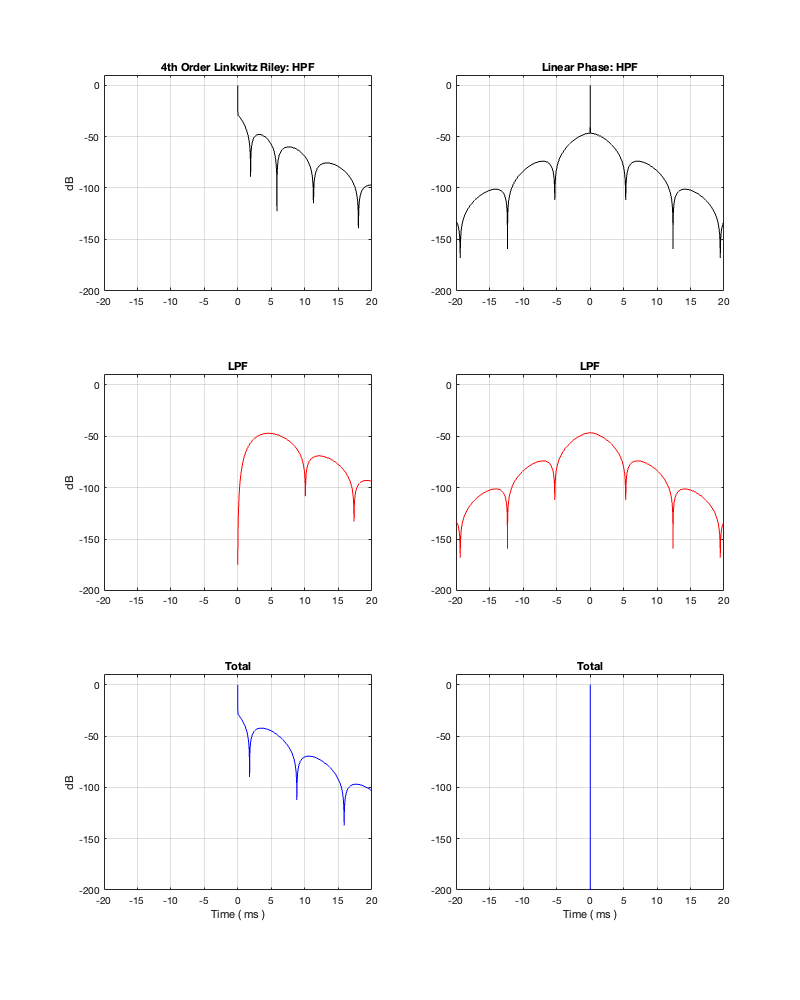

So, let’s look at the same plots for a crossover that is one decade lower: at 100 Hz.

Figures 12.6 to 12.8 show the same plots for at 100 Hz crossover. HOWEVER: notice that the scale of the x-axis has changed to ±20 ms instead of ±5 ms. Also note that, despite me extending that scale by a factor of 4, it’s still not enough to get down 200 dB for the linear phase filters.

You can see there (looking at the red curve on the right of Figure 12.8) that, if you’re going to set -100 dB as your threshold, then you will have to have a latency of about 14 or 15 ms to implement it as a linear phase crossover. (Similar to the 1 kHz version, if you want to go down 200 dB, you’ll need to double this to 28 to 30 ms, which is starting to get close to the acceptable limits for lip-synch with video.)

In the next posting, we’ll look what happens to the magnitude and phase responses if you shorten these impulse responses using a technique called “windowing”.

However, I am NOT going to talk about audibility of a linear phase vs a minimum phase strategy. There are people who love to bang on about ringing and pre-ringing and whether you can hear the “ramp in” of the linear phase filters, or whether the “long” decay time of the minimum phase filters are audible. The best way to stay out of this fight is to not comment on it. If you want to decide whether you can hear these things or not, then you should implement them and have a listen. I can’t tell you what you can or cannot hear. However, if you DO decide to try implementing these for a listening test, make sure that you do it right, that:

- the only difference in the crossovers is what you think it is (If not, you’re not comparing the crossover types in isolation), and

- you are running a blind test (if not you can’t trust your own opinion).

Loudspeaker Crossovers: Part 10

In this posting, we’ll do something similar to the analyses from Part 7. In that one, we

- took two point-source theoretically perfect loudspeaker drivers (which means that they have the same magnitude response in all directions in 3D space), (pretending that they were a tweeter and a woofer in a non-existent cabinet)

- filtered each of their inputs using a crossover network

- separated them by some distance

- measured them in a bunch of places on a sphere surrounding the non-existent cabinet

- found the total magnitude response of the system when measured all around on that sphere, which is called the loudspeaker’s Power Response.

Now, we do that again, but we will include the real loudspeaker drivers’ measurements in that three-dimensional world. In this case, we still have the 1″ tweeter and the 6″ woofer in a sealed cabinet. Those two loudspeaker drivers were individually measured at 130 points around them on that sphere that I showed in Part 7.

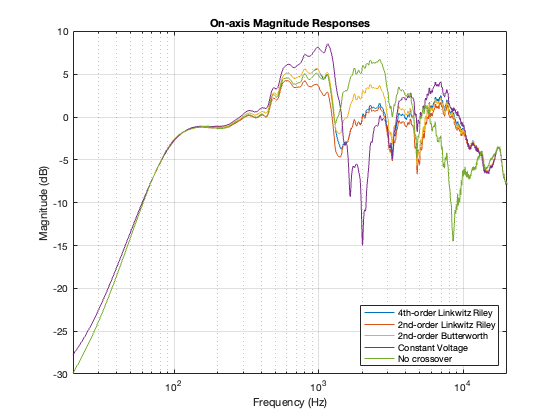

I then take each of those 130 measurements for each driver, filter them using the crossover, and add the two outputs together, which gives me the magnitude response of the entire loudspeaker with two drivers for each individual location. We then add the 130 measurements to find a total combined response which is the Power Response of the two-way loudspeaker with two real loudspeaker drivers in a real cabinet, with the 5 different crossover types that we’ve been talking about.

Note that I have NOT done what I said I SHOULD do at the end of part 9. I have just been dumb and stuck the crossovers in front of the loudspeaker drivers without thinking about modifying the filters to compensate for the drivers’ characteristics.

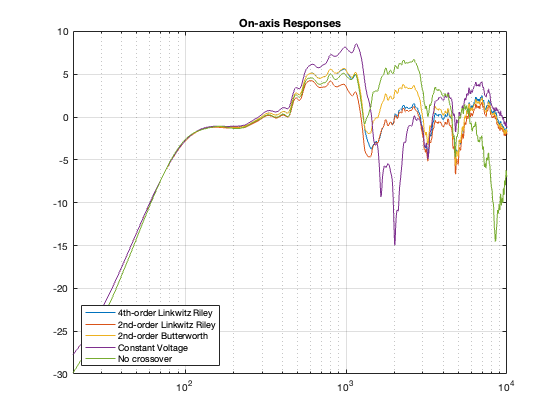

The five resulting power responses are shown in Figure 10.1.

The first thing to notice is that there is a roll-off in the low end. This is the natural response of the woofer that we saw in Part 9.

The second thing that you’ll notice is the general downward-slope in the top octave of the plot, starting at about 7 kHz and having a generally decreasing magnitude the higher you go in frequency. This is the result of “beaming”. Since the two loudspeaker drivers, generally, have less and less high-frequency output as you move off-axis, then this appears as less total output from the system on that sphere. If the two loudspeakers were omnidirectional, then the power response would be a horizontal line. The more directional the drivers, the steeper the downward slope of this plot.

The last thing that’s easy to see in this plot is the transition between the woofer and the tweeter. It appears as that steep slope just above 1 kHz. Remember that I put the crossover at 1.8 kHz – so the slope doesn’t sit right on the crossover frequency. But it’s easy to see that something is happening to the directivity of the loudspeaker in that area.

Now remember back to Part 7, where we did a little trick where we made an assumption that a person building or installing a loudspeaker would measured its on-axis response, and then put in an equaliser to flatten this measured response.

In the old days, you would do this “by eye” using something like a graphic or a parametric equaliser. But nowadays, we have fancy tools that can do measurements and create complicated FIR filters that do whatever we want. This means that we can REALLY screw things up with the precision of a surgical scalpel…

So, let’s be dumb and do the same thing again. We’ll take the on-axis responses of the loudspeaker with the different crossovers (we already saw these in Part 9, but here they are again, shown in Figure 10.2), and we’ll make five “perfect” equalisers that make each of these five responses perfectly flat.

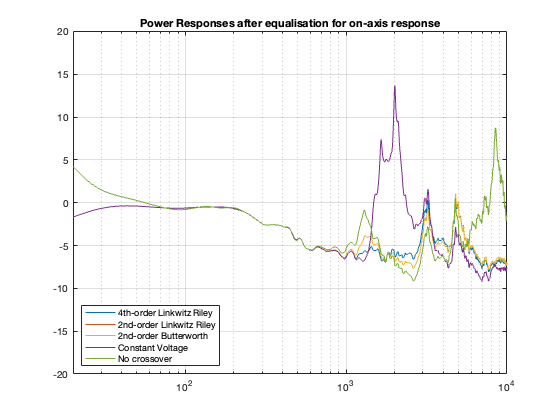

After applying each of these customised filters that make our on-axis measurement look like a laser beam, we should probably check what happened to the power responses. They’re shown below in Figure 10.3.

As you can see there, the low frequency response flattens out. This is because we’re really boosting the bass (to fix the on-axis measurement) and this loudspeaker happens to be fairly omnidirectional below about 200 Hz.

You can also see that I was REALLY dumb when I made those equalisation filters. For example, the notch in the on-axis response of the Constant Voltage caused me to make a horrendous peak that results in a really nice-looking plot at one on-axis point in space, but completely messes up the response of the loudspeaker in almost all other directions, resulting in that giant 15 dB peak around 2 kHz (remember that our crossover frequency is in this region…). I also wound up pushing up the low end by something like 30 dB, which is nuts.

The moral of this story is “don’t fix the on-axis response without considering the power response”. OR “just because it looks flat doesn’t mean that it’ll sound good.” On the other hand, notice that, after equalisation, most of the other curves look pretty similar-ish which means that maybe doing some intelligent equalisation for the on-axis response isn’t necessarily a bad idea.

Remember, however, that we’re still only looking at the loudspeaker in infinite space. There’s no room “singing along” with this loudspeaker… but the topic of room compensation is for another time…

N.B. About a week after I made this posting, I found an error in my Matlab code that calculated the plots. They’ve now been updated to the correct curves. The conclusions listed in the text haven’t changed, but some of the little details have.

Extra note for the sake of transparency

Figure 10.3 was made using a method that is about as stupid and lazy as I could have possibly done. For each crossover type, all I did was to subtract the values shown in the plot in Figure 10.2 from those in Figure 10.1. This is probably not the way that you would implement a “flattening” filter in real life, but it is similar to the old-fashioned strategy used by systems that blindly make an FIR filter based on a single measurement.

Loudspeaker Crossovers: Part 9

Up to now, we’ve either assumed that we don’t have any loudspeaker drivers in the chain (Parts 1 to 5 inclusive) or that our loudspeaker drivers are “perfect” point sources (Parts 6 to 8 inclusive). This means that, so far, our nice, perfect world has used a model that looks a little like Figure 9.1

Now, we start getting a little closer to reality by adding some actual loudspeaker drivers to the outputs of the crossover. Going forward, I’m using the actual measurements of a real 1″ tweeter and a real 6″ woofer in a real sealed cabinet. So, now, instead of just looking at the magnitude and phase responses of the crossover’s outputs, we’re looking at the responses of the outputs of the drivers, as shown in Figure 9.2. Another way to think of this is that we have extra filters (the drivers’ responses, which are different in different directions) in addition to the filters in the crossover.

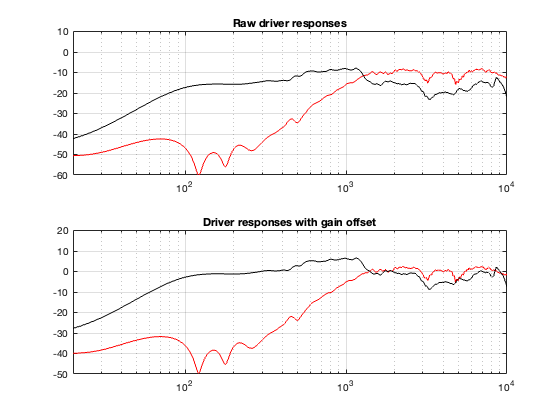

The problem with real loudspeakers is that they aren’t perfect, so let’s start by looking at their responses on-axis. These are shown in Figure 9.3

The top plot of Figure 9.3 shows the on-axis magnitude responses of the loudspeaker drivers in the cabinet without any filtering. The bottom plot shows the same responses, with gain offsets to match them at an arbitrary crossover frequency of 1800 Hz.

4th Order Linkwitz Reily

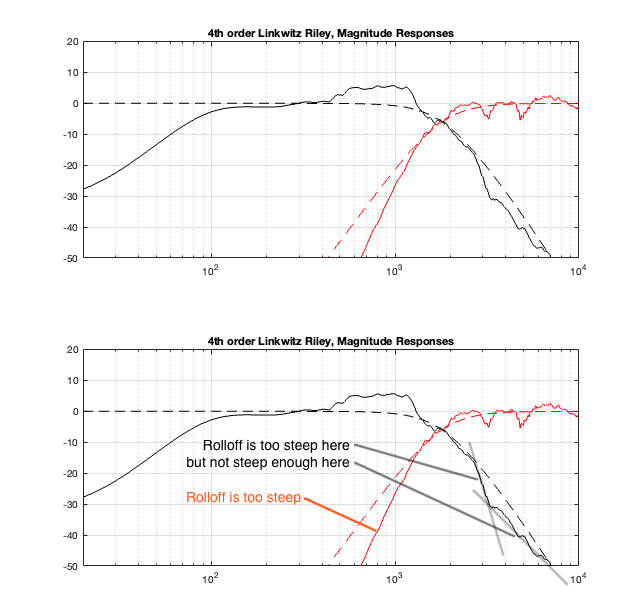

If I apply filtering using a 4th-order Linkwitz Reily crossover, and then send its outputs to a tweeter and a woofer, the resulting magnitude responses of the two drivers, when measured on-axis to the cabinet will look like the top plots in Figure 9.4, below.

I’ve duplicated the plot in the bottom half of the figure, and added some comments. Notice that the responses of the actual loudspeaker outputs, including the crossover filter, do NOT look like the theoretical responses of the crossover itself (shown as dotted lines). On-axis, the tweeter has a natural high-pass characteristic (seen in Figure 9.3) that, when combined with the high pass filter in the crossover, results in a slope that’s too steep.

The woofer’s rolloff is weird in that its contribution makes the low pass filter too steep at the start of the rolloff, and then not steep enough as you get a little higher in frequency. If you look back to Figure 9.3, this can be seen as the dip in the response that produces the “bowl” shape from roughly 1 kHz to 8 kHz.

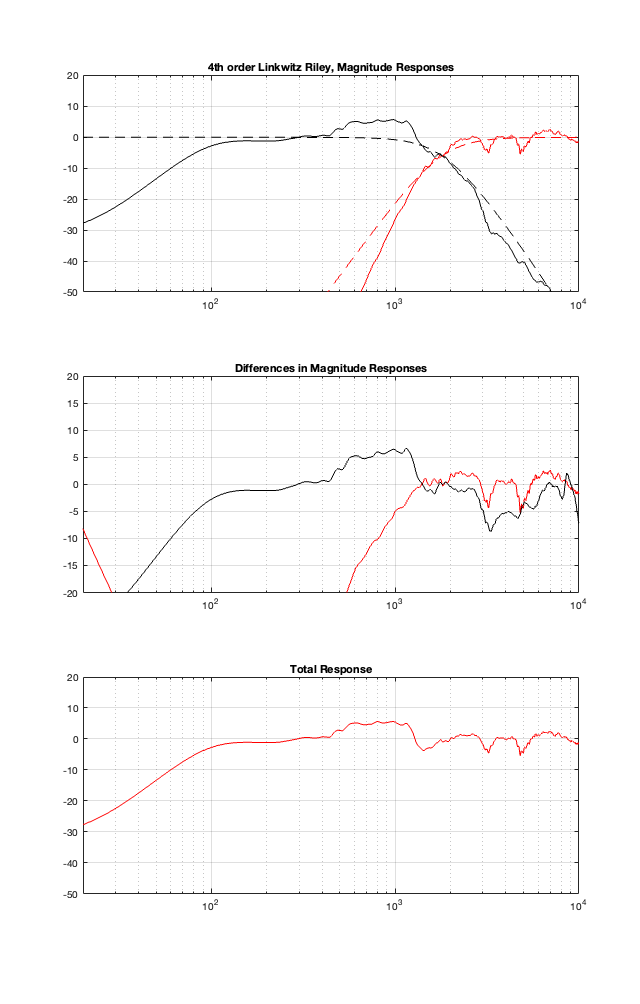

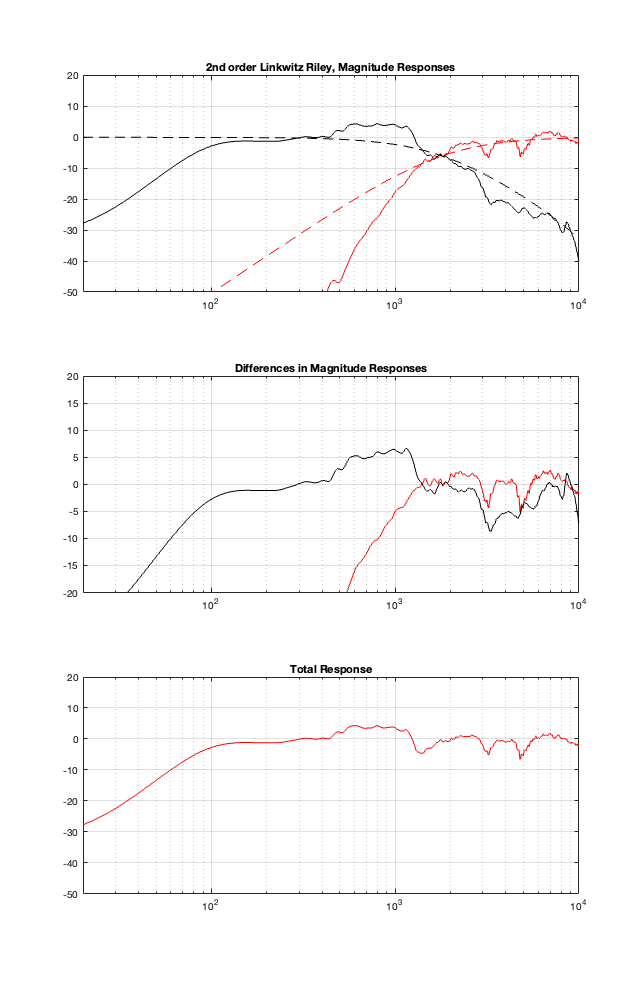

This means that, if we ignore the natural on-axis magnitude and phase responses of the loudspeaker drivers, and just slap a crossover in front of them, the resulting total response won’t be as pretty as we would expect. This is shown in the bottom plot in Figure 9.5.

The plots shown in the middle of Figure 9.5 are the difference between what we WANT the crossover to be (the dotted lines in the top plot) and the ACTUAL total resulting magnitude response at the outputs of the drivers (the solid lined in the top plot). In other words, these curves show the vertical distance between the solid and dotted lines in the top plot. If the drivers had perfectly flat magnitude responses, then these two lines would be flat, and they would sit on the 0 dB line.

You might say that the Total Response in Figure 9.5 looks pretty good. I would disagree. An on-axis in-band magnitude response of about ±5 dB is pretty terrible if your goal is a flat on-axis response. If this is not your goal, then I have no opinion.

Now I’ll just throw in the same plots for the different crossover types, implementing the crossover with the assumption that the loudspeaker drivers are perfect, and then doing the analysis including the actual responses of the drivers.

2nd order Linkwitz Reily

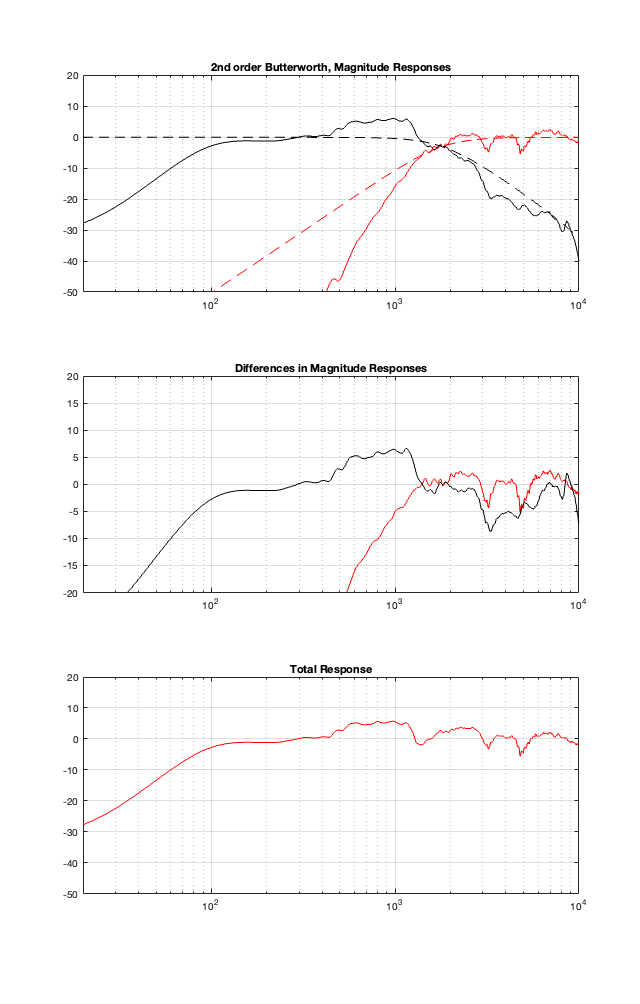

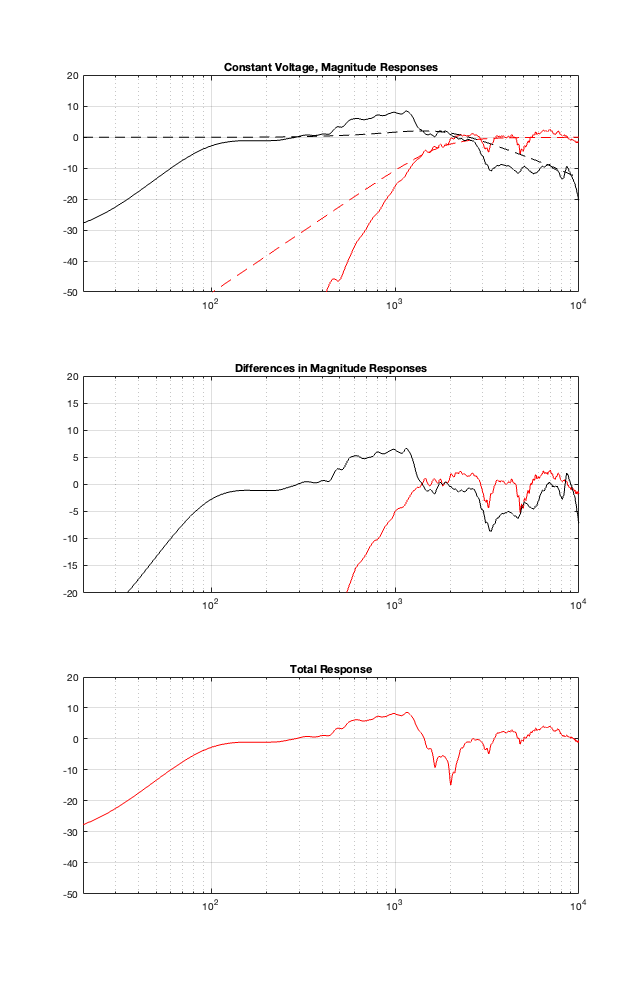

2nd order Butterworth

Constant Voltage

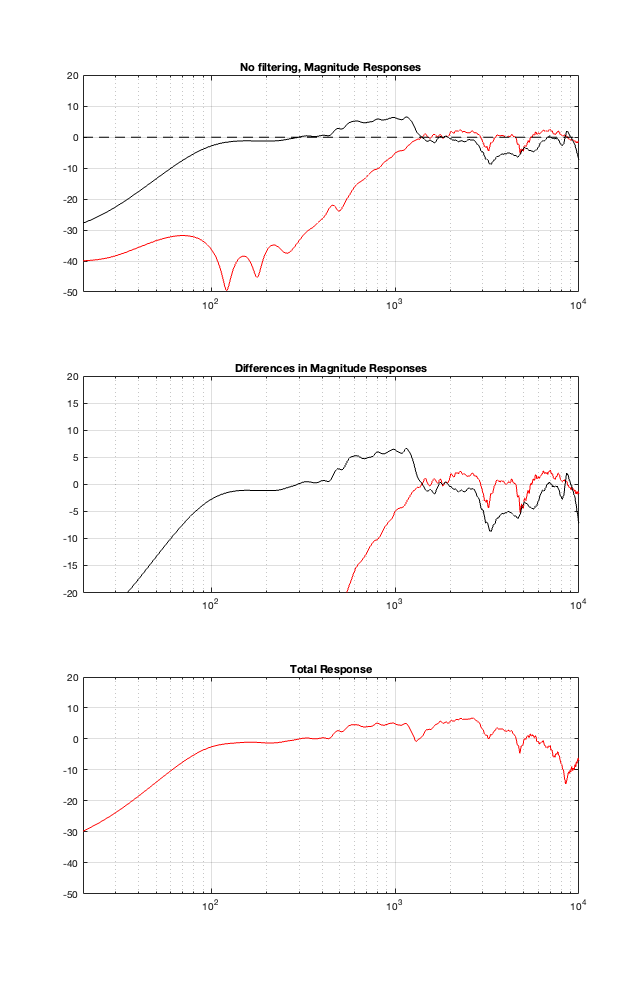

No Crossover

Comparison

I’ll let you draw your own conclusions about the results of these plots. I will highlight one thing: remember that the theoretical combined magnitude responses of the 4th order Linkwitz Riley and the Constant Voltage crossovers are both flat. But compare their Total Responses in the plots above. Notice that they are very different from each other. This is, in part, because the phase responses of the two signal paths are modified by the driver’s behaviours, which means that they don’t add as nicely as we would like.

The moral of the story this time is: you can’t ignore the natural response of the drivers when you’re designing your crossover. This means that we will need to change our filters to ensure that the TOTAL response of the filter PLUS the driver results in the response that we want. The design of the crossover MUST include the responses of the drivers to ensure that it behaves as we wish.

But, so far, we have only considered this at one point in space, directly in front of the loudspeaker. In the next posting, we’ll come back to looking at the total power response. Things are about to get ugly…

Loudspeaker Crossovers: Part 8

This will be a short posting with very little new information. I’m just starting to put some of the Lego blocks together to make it easier later on.

For this posting, I’ve taken two different pieces of information that you already have, and put them together.

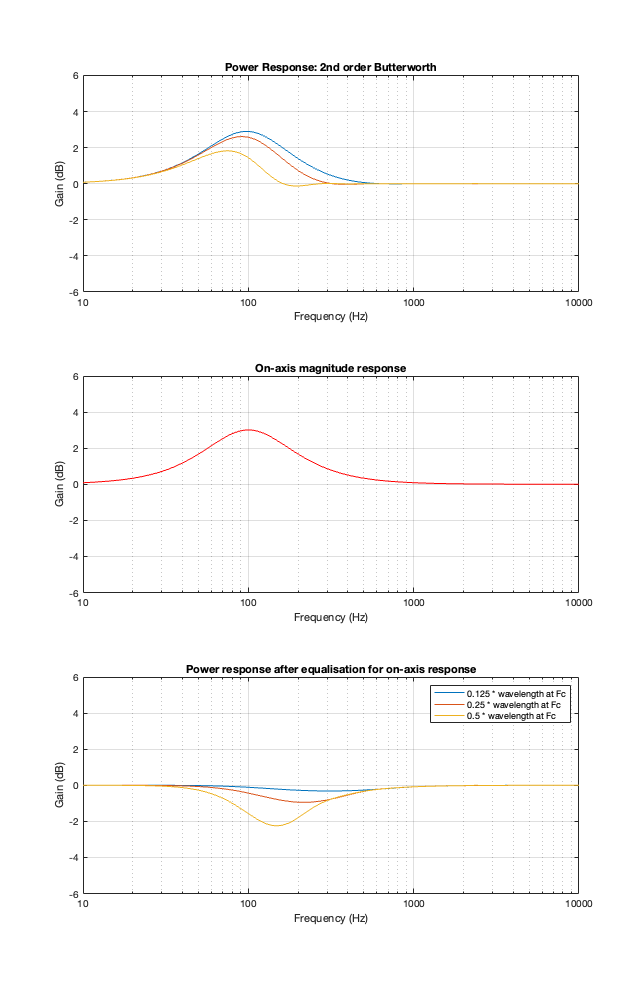

2nd order Butterworth

Take a look at Figure 8.1 below, which shows information related to a 2nd order Butterworth crossover at 100 Hz.

The top plot shows the power responses, explained in Part 7.

The middle plot shows the on-axis magnitude response, which will be the same regardless of the separation between the loudspeaker drivers because I’m assuming that they’re perfect point-sources.

IF you built such a loudspeaker, then chances are that you would put in an equaliser at the input of your loudspeaker to make the on-axis response flat instead of having that bump. That equaliser would, in turn effect the entire power response. So, the bottom plots show the power responses of the loudspeaker (with three different driver separations) AFTER you’ve applied the equalisation to correct for the on-axis magnitude response.

In other words, the top plots MINUS the middle red plot equals the bottom plots

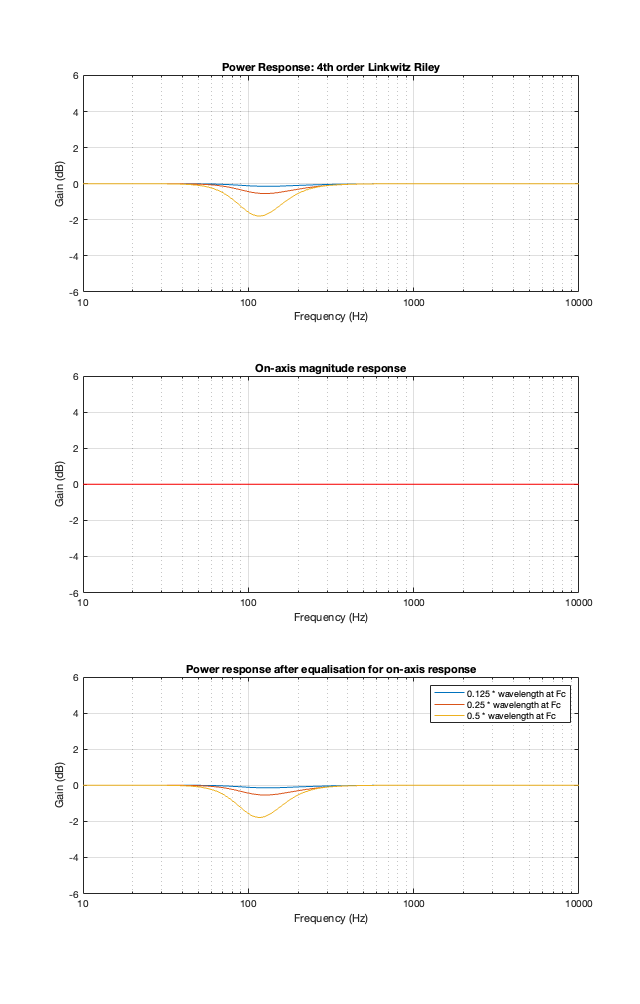

4th-order Linkwitz Riley

The 4th-order Linkwitz Riley’s power response does not change because its on-axis response is flat, so there’s nothing to correct.

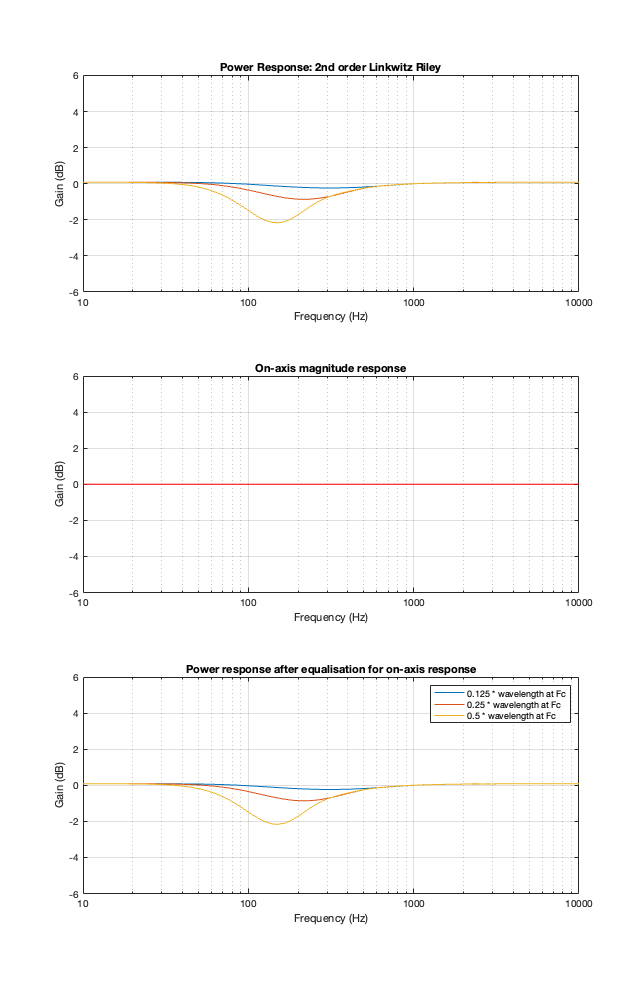

2nd-order Linkwitz Riley

The 2nd-order Linkwitz Riley’s power response does not change because its on-axis response is flat, so there’s nothing to correct.

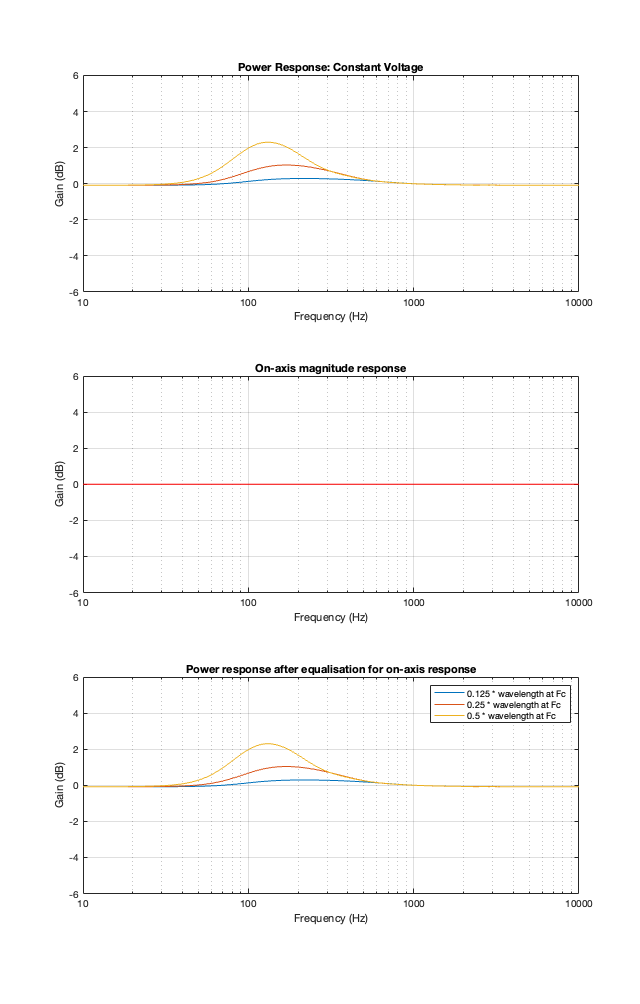

Constant Velocity

The Constant Velocity’s power response does not change because its on-axis response is flat, so there’s nothing to correct.

Like I said: there’s no new information here. It’s just a reminder that, if you add equalisation for your on-axis response (whether this is part of your loudspeaker-building process or your installation in the listening room), you will also have a subsequent on the power response. Since the equalisation is applied to the loudspeaker’s input, the on-axis and power responses are locked together. Change one, and you change them both.

Loudspeaker Crossovers: Part 7

Power Response

There are different ways to evaluate the behaviour of a loudspeaker. Most people like looking at the on-axis magnitude response, which is a nice and simple perspective through which one can view the universe. However, it can be VERY misleading to look at the universe from only one perspective.

As I pithily said at the end of the last posting, if you lived in an anechoic chamber and you only ever sat directly in front of your loudspeaker, then maybe you could justify being concerned only with the on-axis magnitude and phase responses of your loudspeaker. However, if you live in the real world, it’s wise to consider that some other areas of three dimensional space are also interesting – possibly even mores.

In the last posting, we moved from 0 spatial dimensions (up to Part 5, we hadn’t considered space at all…) to one dimension (I’m thinking in a geographical, or spherical view where space is defined as a horizontal and a vertical angle, and a distance, instead of X, Y, and Z coordinates. Of course, these two methods of defining space are interchangeable, if you wish to convert.) Moving vertically in that one angular dimension, we saw that the different crossover types had an effect on the directivity of the total output of the system.

Now we’ll extend to a three-dimensional world, which means that we’ll need to define space using two angles, however, don’t worry… everything will probably look familiar to you.

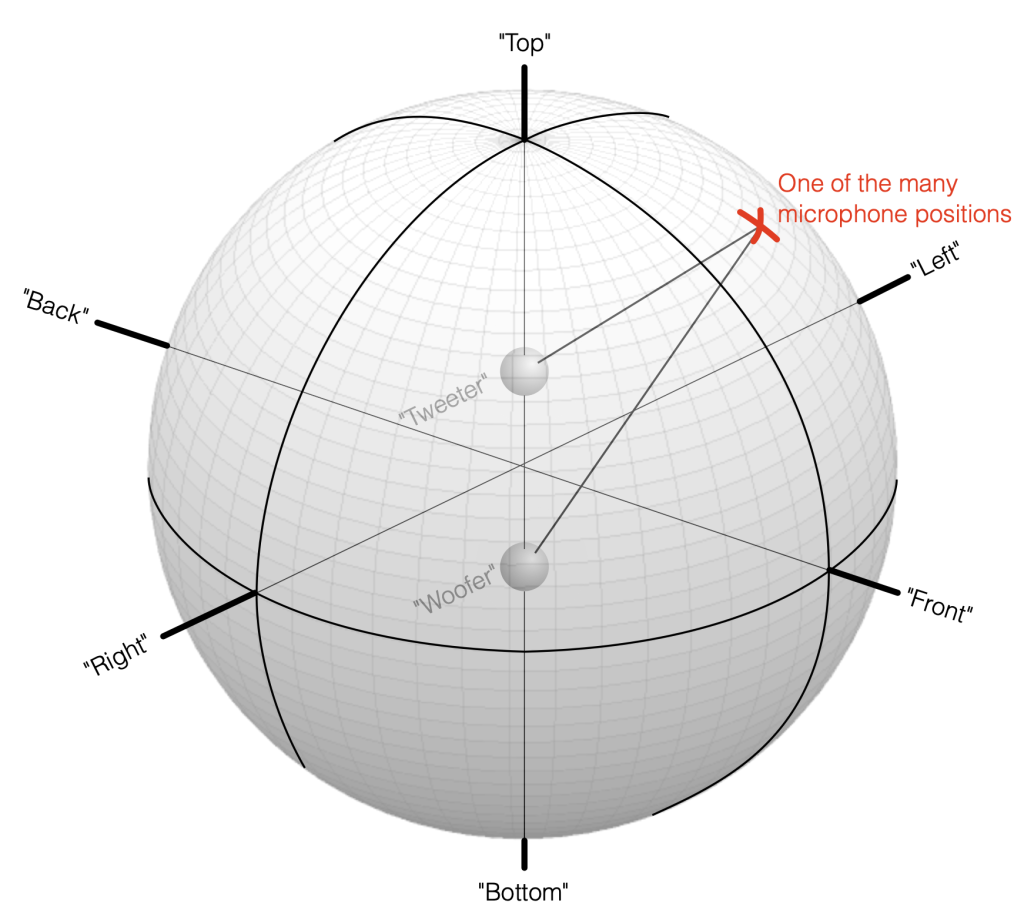

Take a look at Figure 7.1. I’ve now placed our two “perfect” omnidirectional point-source loudspeaker drivers in a three-dimensional space inside a giant sphere. I’ve called them a “tweeter” and a “woofer” again, just for the sake of clarity, but the truth is that I’m just treating them as full-range sources that are omnidirectional in all three dimensions.

We can then place our microphone at some location on the surface of that imaginary sphere, at some horizontal angle and some other vertical angle. You can consider the analysis I did in Part 6 to be a “slice” of this sphere, on the line that extends from the Bottom to the Top, running through the Front.

Sidebar

Put a real loudspeaker in your living room and listen to it from out in the kitchen while you make dinner. The loudspeaker radiates sound in all directions in all three dimensions, and that spherical ball of energy is more related to what you’ll hear bleeding into the kitchen than the simple on-axis response. No one is sitting in front of the loudspeaker, so there’s no one there to care about the on-axis response at all…

Let’s move microphone around the surface of that big sphere in Figure 7.1, making a measurement of the combined outputs of the tweeter and woofer (including the delay differences caused by the distance between the two loudspeaker drivers and the three-dimensional direction to the microphone) in each place. Since the two drivers are separated in space (among other things) they’ll result in a different measurement in each location. If we then combine all of those measurements to find the total magnitude response of the three-dimensional radiation, we’ll find the total Power Response of the system. This is the combined response of the loudspeaker’s output in all three dimensions, which is what we’re looking at in this article.

There are different ways to move around that sphere and then sum the numerous measurements that you get as a result. However, if you do the math correctly, it doesn’t really matter which way to do this.

I won’t say much more here; I’ll just show the plots. Each of the Figures below has three lines on it, showing three different separations between the two loudspeaker drivers. As in the previous postings, these are 0.125, 0.25, and 0.5 * the wavelength of the crossover frequency, which, in this case is 100 Hz.

This allows you to compare the tendency of the power response characteristic as the driver separation increases.

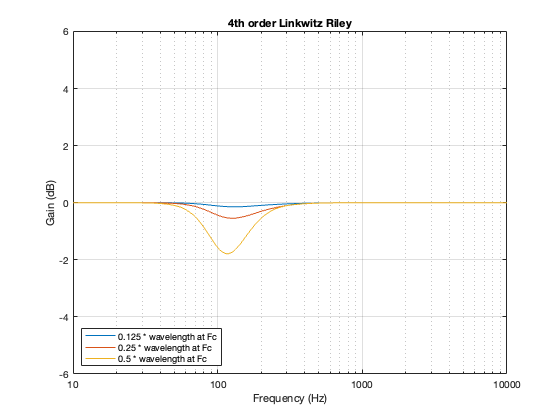

4th order Linkwitz Riley

Notice that the Power Response of the 4th-order Linkwitz Riley only drops in magnitude around the crossover frequency, and the depth and bandwidth of that dip is dependent on the distance between the drivers.

It’s also worth putting in the reminder here that if we moved the crossover to a different frequency, then the behaviour would look the same, just moved upwards or downwards on the x-axis. This is because I’m determining the distance between the two drivers using the wavelength of the crossover.

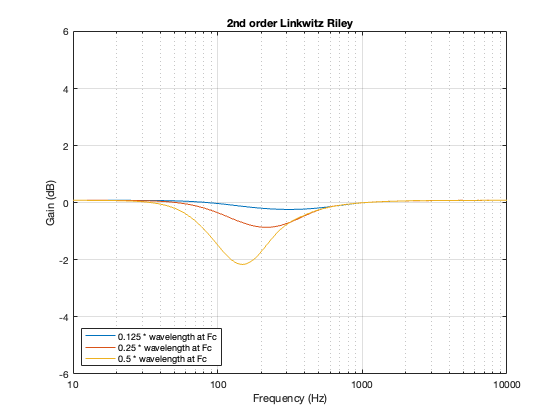

2nd order Linkwitz Riley

A 2nd-order Linkwitz Riley has a similar power response to the 4th order, although the effect is increased a little in frequency above the crossover, and it dips a little more for the same separation between the drivers.

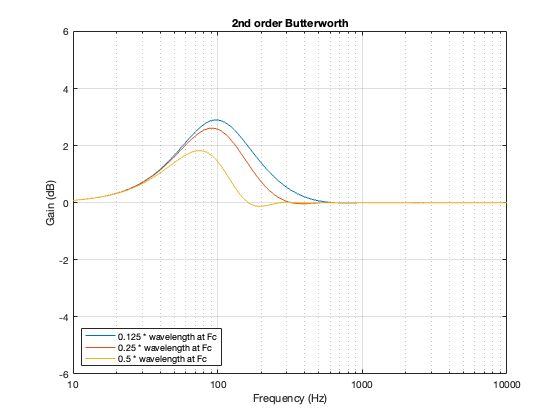

2nd order Butterworth

A 2nd-order Butterworth’s power response exhibits the opposite effect. It. produces a bump in around the crossover frequency instead of a dip. Also notice that the magnitude of the bump is more pronounced with the same distance between the loudspeaker drivers. Whereas a separation of 0.125*wavelength produced only a very slight dip in the power response for the two Linkwitz Riley crossovers, the same separation results in a more than 2 dB increase for the Butterworth design. Oddly, the bump gets smaller with larger separation – but this is a function of the relationship between the phase responses of the Butterworth filters and the delays of the two driver outputs at the various microphone positions around the sphere.

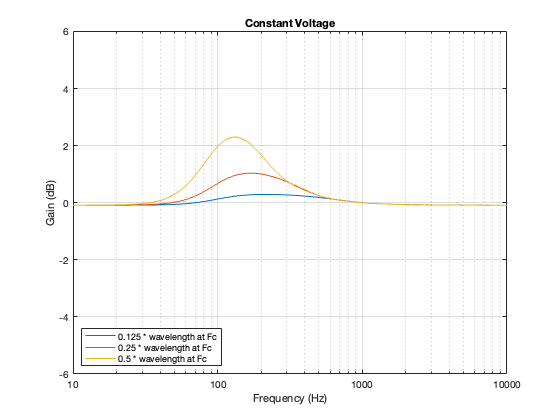

Constant Voltage

The constant voltage crossover is a little more intuitive in that the larger the separation between the drivers, the bigger the effect on the power response. In addition, it behaves similarly to the Butterworth design in that it produces a bump relative around (actually, just above) the crossover frequency.

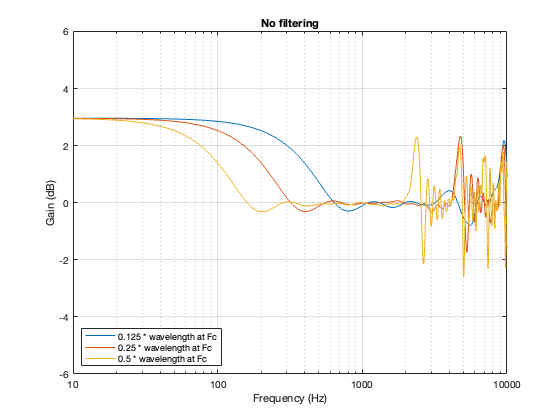

No Crossover

Again, just for curiosity’s sake, it’s interesting to look at the effect of having two drivers with the same separation as the models shown above, but without the filtering applied by a crossover. This is shown below in Figure 7.6. in the very low frequency band, you can see that the two drivers sum to give a 3 dB boost, which is equivalent to double the total power radiated by the system. The closer the two loudspeaker drivers are to each other, the higher the extension of this boost.

In addition, the strange effects in the high frequencies are essentially identical, but move up by one octave for each halving of distance between the drivers. You can also see that the interference effect is repeated each octave (notice the way that the orange and yellow lines overlap around 4 kHz, for example).

As I said in the sidebar above, if you do nothing but put in these crossover types, and your two loudspeakers are two little omnidirectional sources, then these plots will give you an idea of the difference in spectral balance that you’ll hear out in the kitchen when you play music. Of course, you would never do this. You would normally put in some extra filtering to fix things (whatever that means). In the next posting, we’ll look at what happens when you do that.