I’ve been debating writing a series of postings about “high resolution” audio for a long time – years. Lately, (probably because of some hype generated by some recent press releases) I’ve been getting lots of question (no, that’s not a typo) about it, so it appears the time has come…

To start: the question that I get (a lot) is “If I can’t hear above 20 kHz, then what’s the use of high-res?” As I’ll explain as we go through, this is only one, rather small aspect to consider in this topic. In fact, it might be the least important issue to consider.

However, before I write too much, I’ll say that I’m not going to argue for or against higher resolutions in digital audio systems. I’m only going to go through a bunch of issues that can be used to argue either for or against them. So, there’s not going to be a big reveal at the end of this series telling you that high-res is either better, worse, or no different than whatever you’re using now. It’s merely going to be a discussion of a number of issues that need to be weighed. The problem is that this entire topic is complicated – and there’s no single “right” answer, as I’ll argue as we go along.

To start, let’s get down to basics and look (once again, from the perspectives of this website) at what sound is, and how it’s converted from an analogue electrical signal into a digital representation. The good thing is that I’ve written this introduction before in a different series of postings. So, I’m going to be extremely lazy and just copy-and-paste that information here. I’m not just referring you to another page because I’m intentionally leaving some things out because we’re headed into having a different discussion this time.

A quick introduction to sound

At the simplest level, sound can be described as a small change in air pressure (or barometric pressure) over short periods of time. If you’d like to have a better and more edu-tain-y version of this statement with animations and pretty colours, you could take 10 minutes to watch this video, for example.

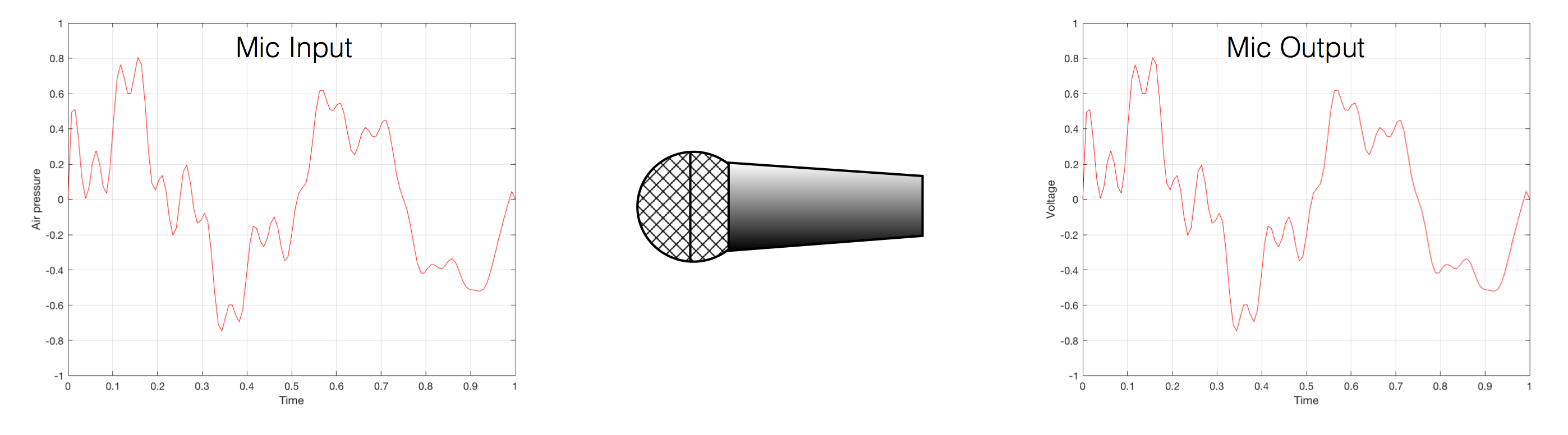

That change in pressure can be “captured” by using a microphone, that is (at the simplest level) a device that has a change in air pressure at its input and a change in electrical voltage at its output. Ignoring a lot of details, we could say that if you were to plot a measurement of the air pressure (at the input of the microphone) over time, and you were to compare it to a plot of the measurement of the voltage (at the output of the microphone) over time, you would see the same curve on the two graphs. This means that the change in voltage is analogous to the change in air pressure.

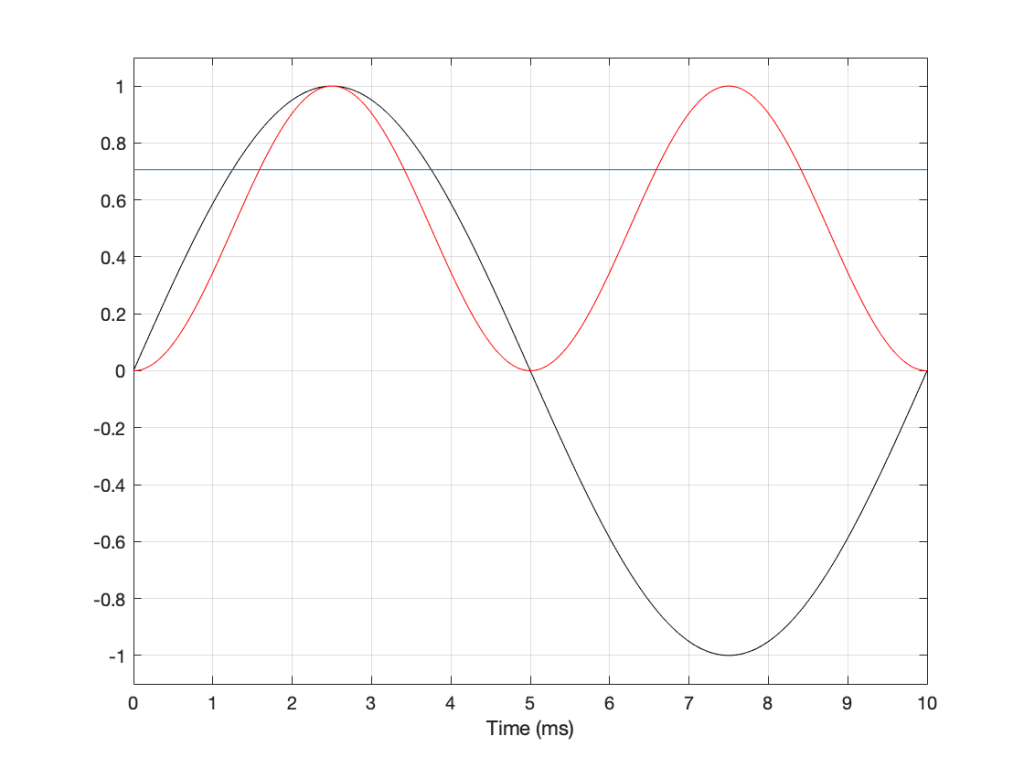

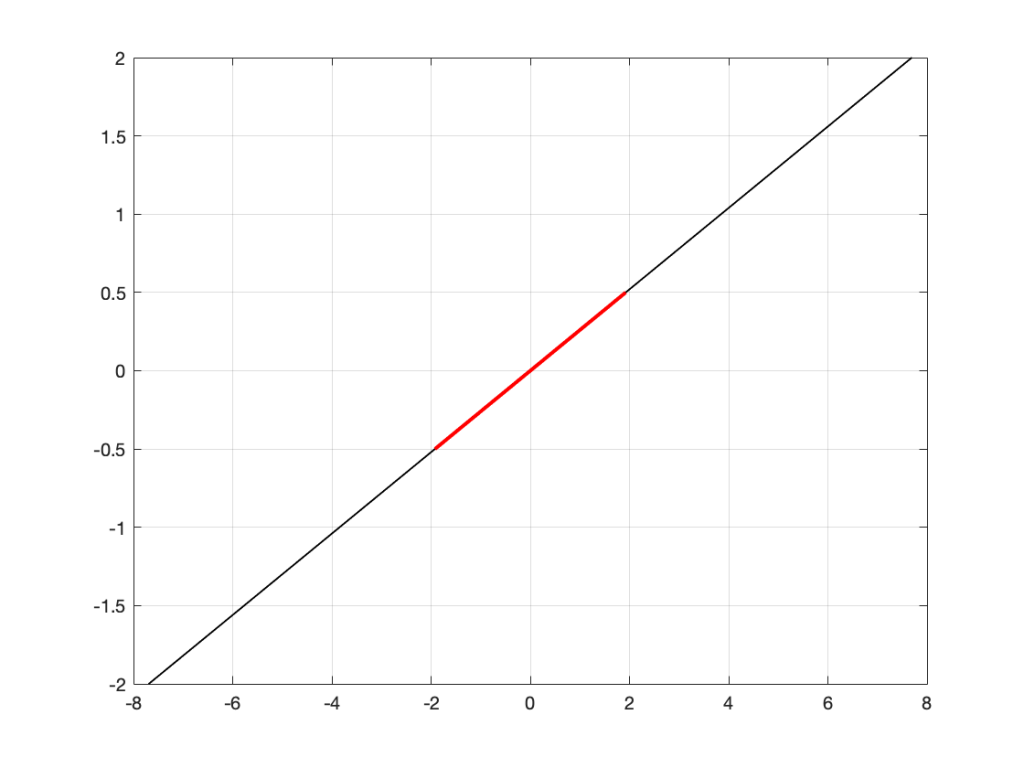

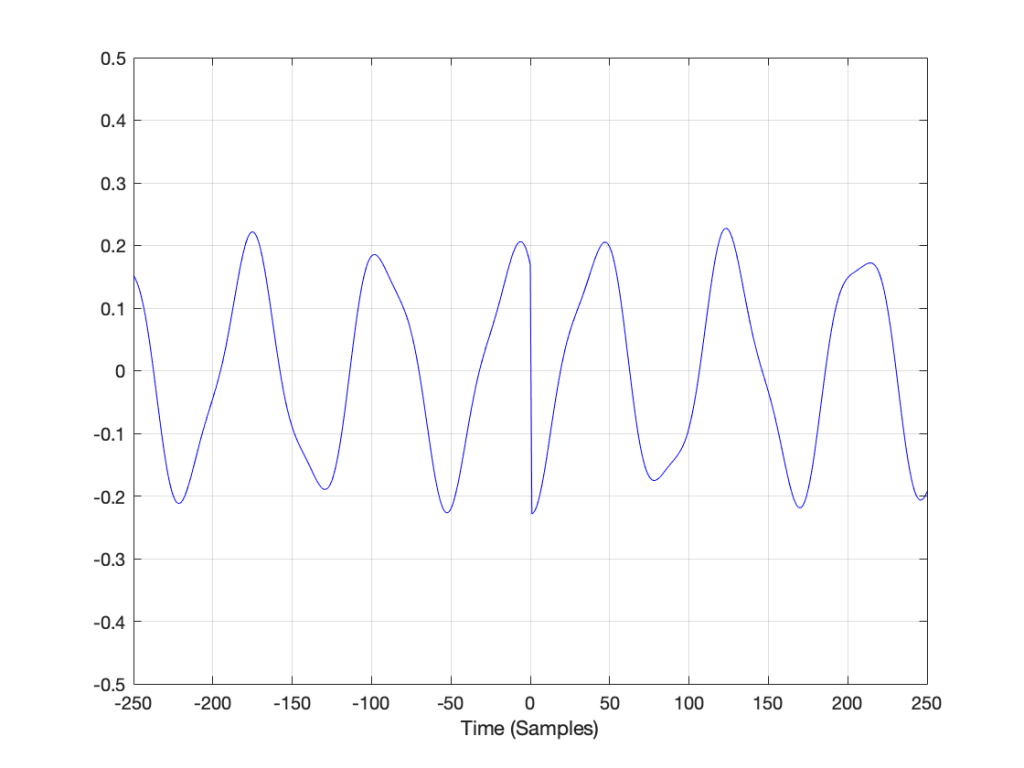

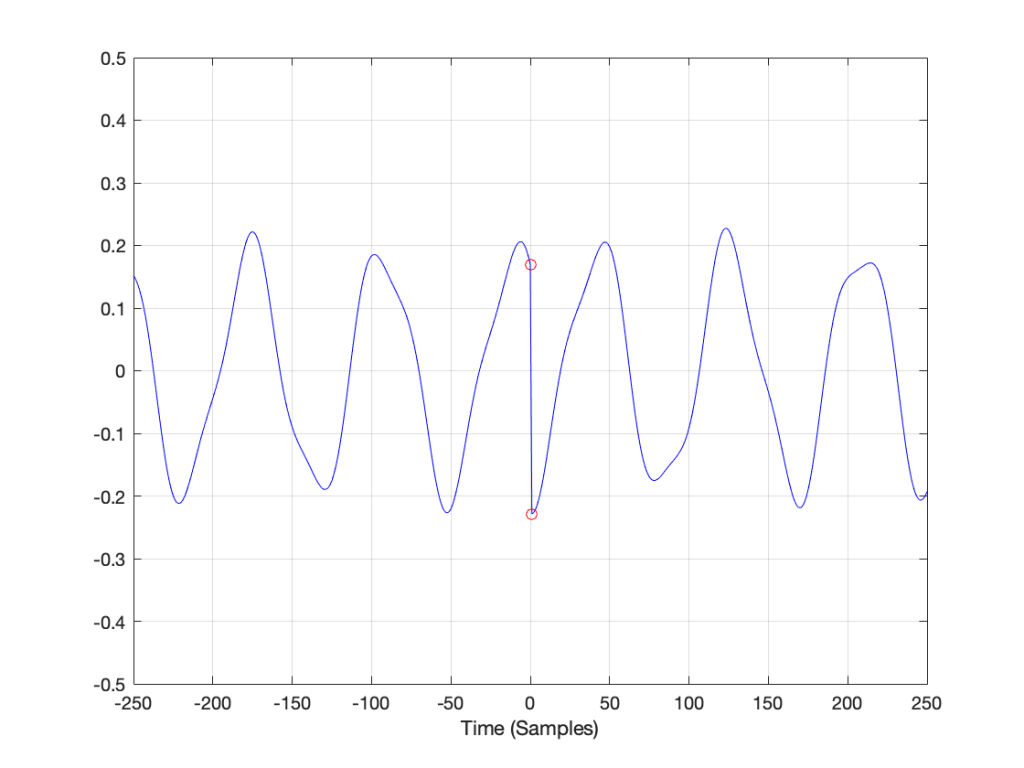

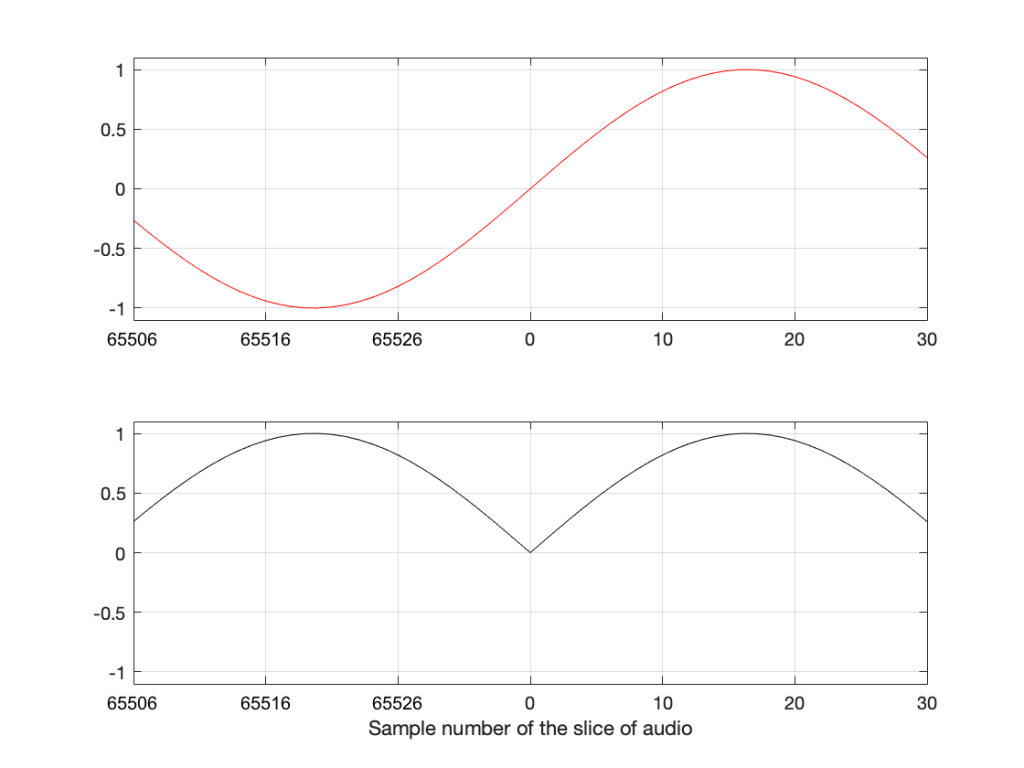

At this point in the conversation, I’ll make a point to say that, in theory, we could “zoom in” on either of those two curves shown in Figure 1 and see more and more details. This is like looking at a map of Canada – it has lots of crinkly, jagged lines. If you zoom in and look at the map of Newfoundland and Labrador, you’ll see that it has finer, crinkly, jagged lines. If you zoom in further, and stand where the water meets the shore in Trepassey and take a photo of your feet, you could copy it to draw a map of the line of where the water comes in around the rocks – and your toes – and you would wind up with even finer, crinkly, jagged lines… You could take this even further and get down to a microscopic or molecular level – but you get the idea… The point is that, in theory, both of the plots in Figure 1 have infinite resolution, both in time and in air pressure or voltage.

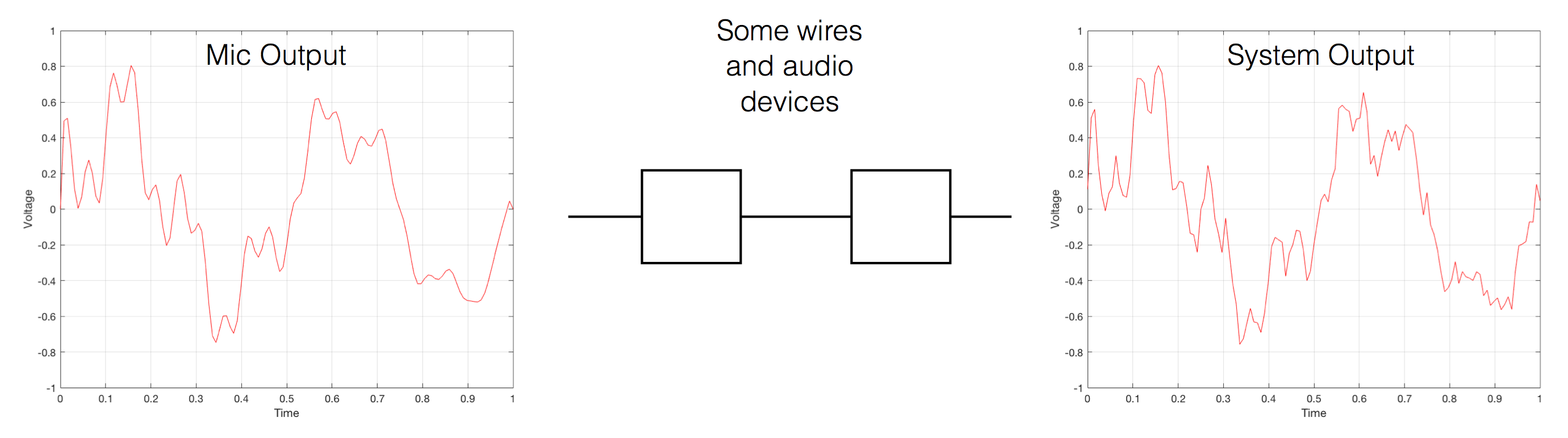

Now, let’s say that you wanted to take that microphone’s output and transmit it through a bunch of devices and wires that, in theory, all do nothing to the signal. Let’s say, for example, that you take the mic’s output, send it through a wire to a box that makes the signal twice as loud. Then take the output of that box and send it through a wire to another box that makes it half as loud. You take the output of that box and send it through a wire to a measuring device. What will you see? Unfortunately, none of the wires or boxes in the chain can be perfect, so you’ll probably see the signal plus something else which we’ll call the “error” in the system’s output. We can call it the error because, if we measure the input voltage and the output voltage at any one instant, we’ll probably see that they’re not identical. Since they should be identical, then the system must be making a mistake in transmitting the signal – so it makes errors…

Pedantic Sidebar: Some people will call that error that the system adds to the signal “noise” – but I’m not going to call it that. This is because “noise” is a specific thing – noise is random – so if it’s not random, it’s not noise. Also, although the signal has been distorted (in that the output of the system is not identical to the input) I won’t call it “distortion” either, since distortion is a name that’s given to something that happens to the signal because the signal is there. (We would probably get at least some of the error out of our system even if we didn’t send any audio into it.) So, we could be slightly geeky and adequately vague and call the extra stuff “Distortion plus noise” but not “THD+N” – which stands for “Total Harmonic Distortion Plus Noise” – because not all kinds of distortion will produce a harmonic of the signal… but I’m getting ahead of myself…

So, we want to transmit (or store) the audio signal – but we want to reduce the noise caused by the transmission (or storage) system. One way to do this is to spend more money on your system. Use wires with better shielding, amplifiers with lower noise floors, bigger power supplies so that you don’t come close to their limits, run your magnetic tape twice as fast, and so on and so on. Or, you could convert the analogue signal (remember that it’s analogous to the change in air pressure over time) to one that is represented (and therefore transmitted or stored) digitally instead.

What does this mean?

Conversion from analogue to digital and back

(but skipping important details)

IMPORTANT: If you read this section, then please read the following postings as well. This is because, in order to keep things simple to start, I’m about to leave out some important details that I’ll add afterwards. However, if you don’t add the details, you could (understandably) jump to some incorrect conclusions (that many others before you have concluded…) So, if you don’t have time to read both sections, please don’t read either of them.

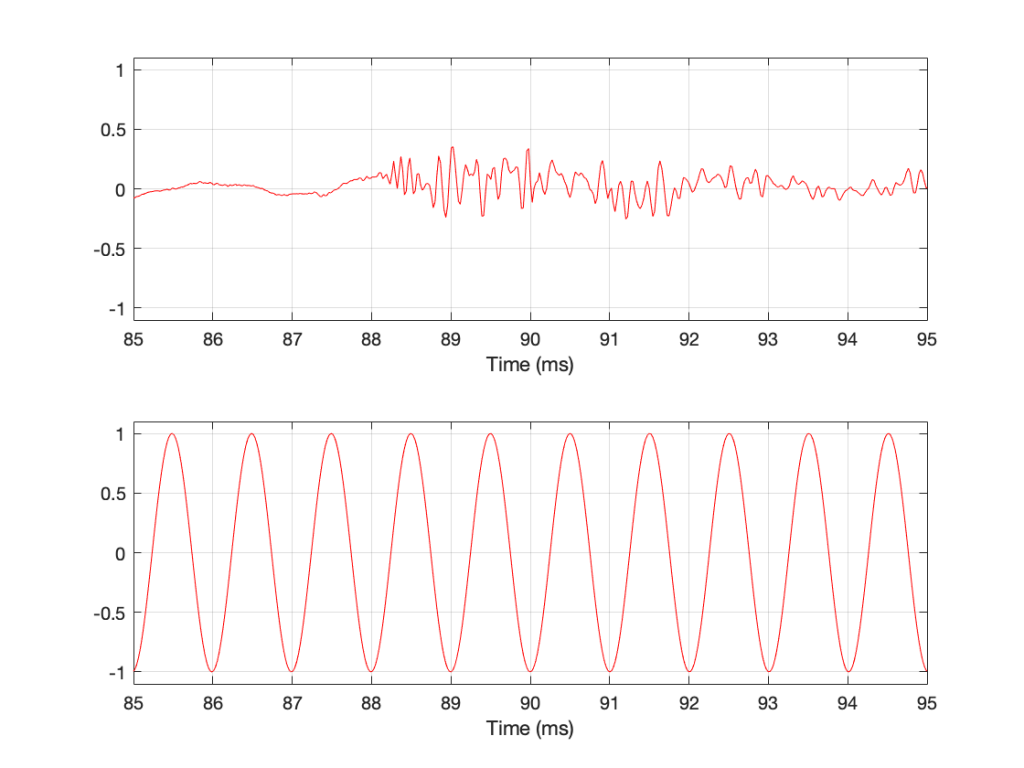

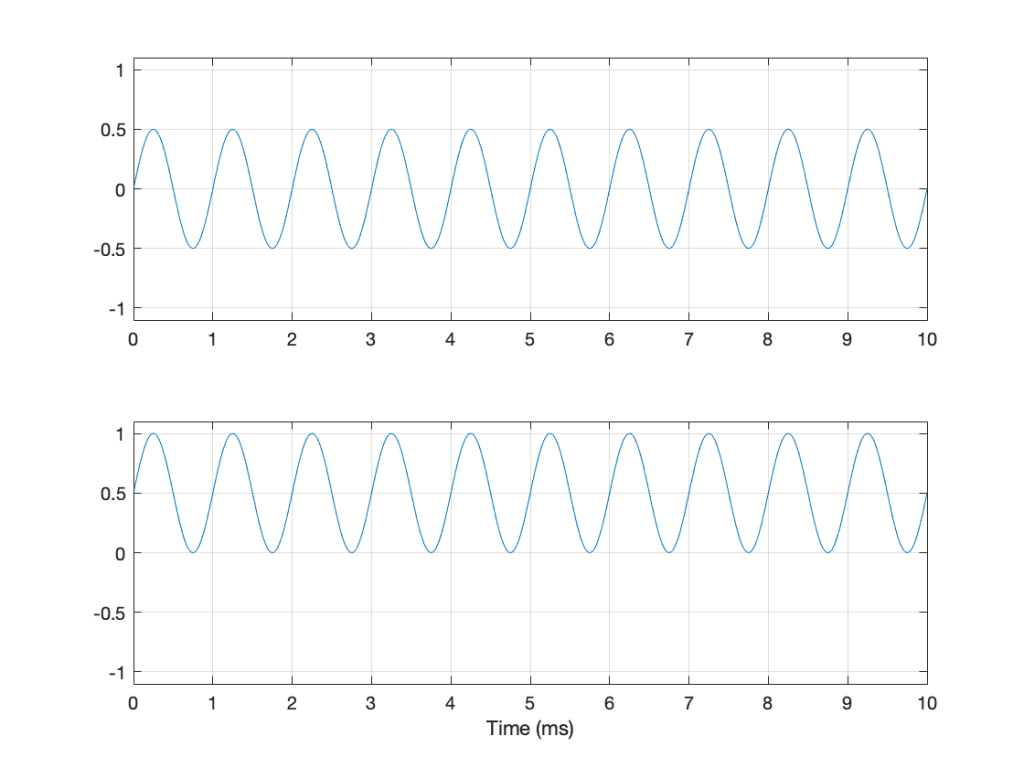

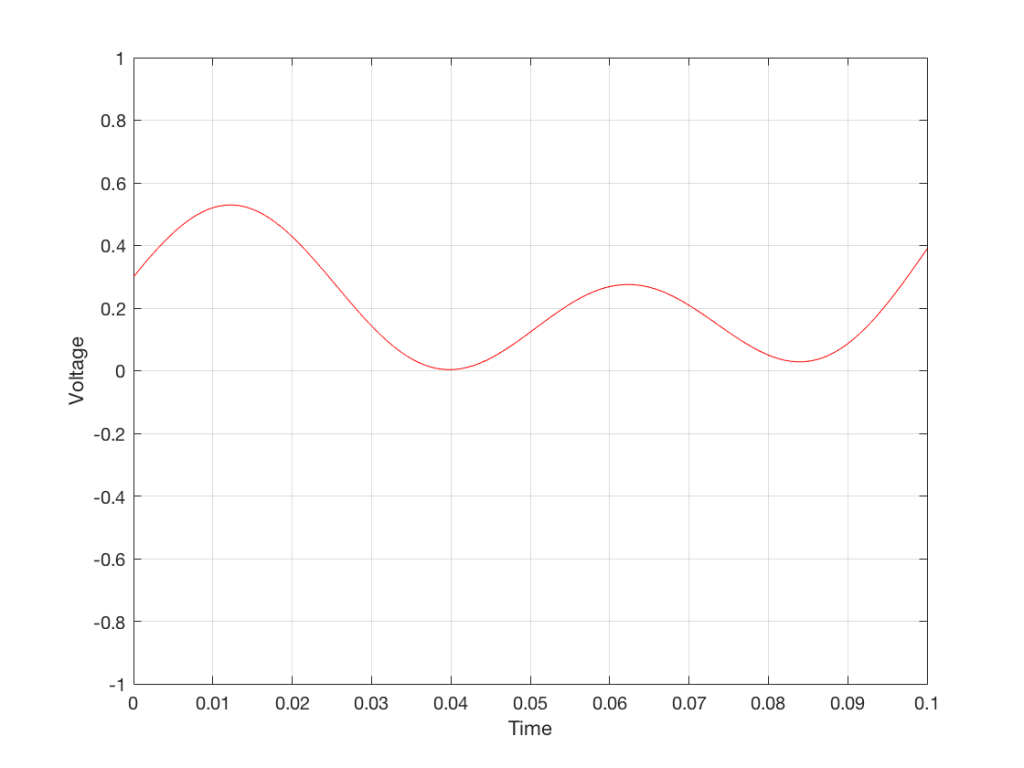

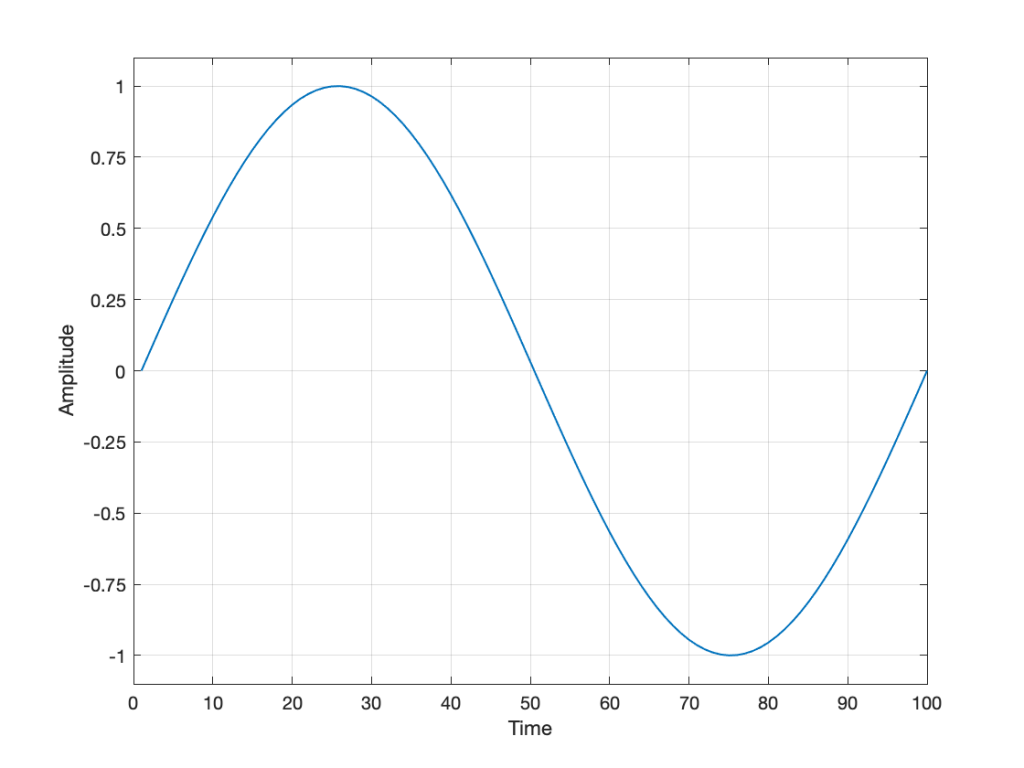

In the example above, we made a varying voltage that was analogous to the varying air pressure. If we wanted to store this, we could do it by varying the amount of magnetism on a wire or a coating on a tape, for example. Or we could cut a wiggly groove in a bit of vinyl that has a similar shape to the curve in the plots in Figure 1. Or, we could do something else: we could get a metronome (or a clock) and make a measurement of the voltage every time the metronome clicks, and write down the measurements.

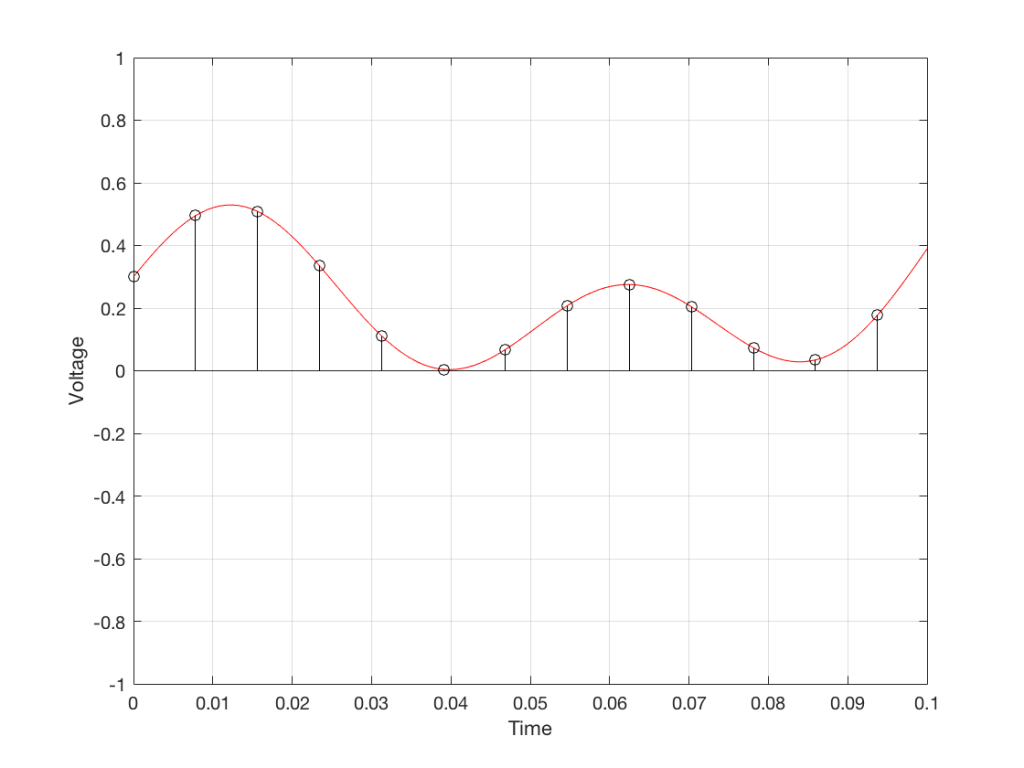

For example, let’s zoom in on the first little bit of the signal in the plots in Figure 1

We’ll then put on a metronome and make a measurement of the voltage every time we hear the metronome click…

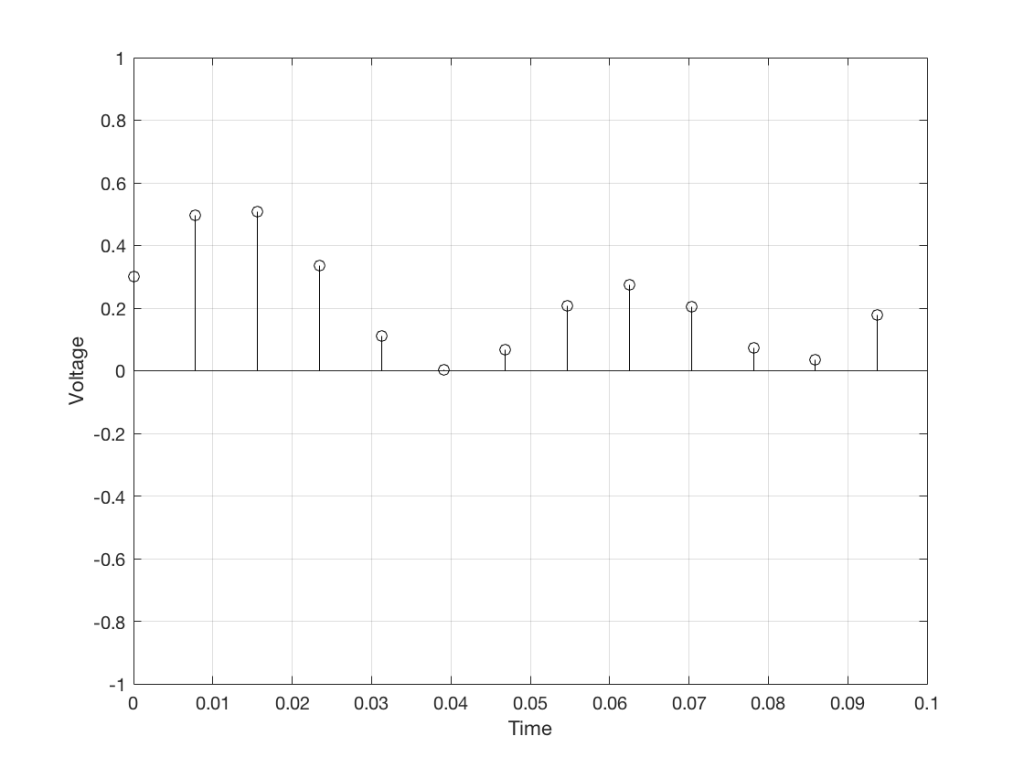

We can then keep the measurements (remembering how often we made them…) and write them down like this:

0.3000

0.4950

0.5089

0.3351

0.1116

0.0043

0.0678

0.2081

0.2754

0.2042

0.0730

0.0345

0.1775

We can store this series of numbers on a computer’s hard disk, for example. We can then come back tomorrow, and convert the measurements to voltages. First we read the measurements, and create the appropriate voltage…

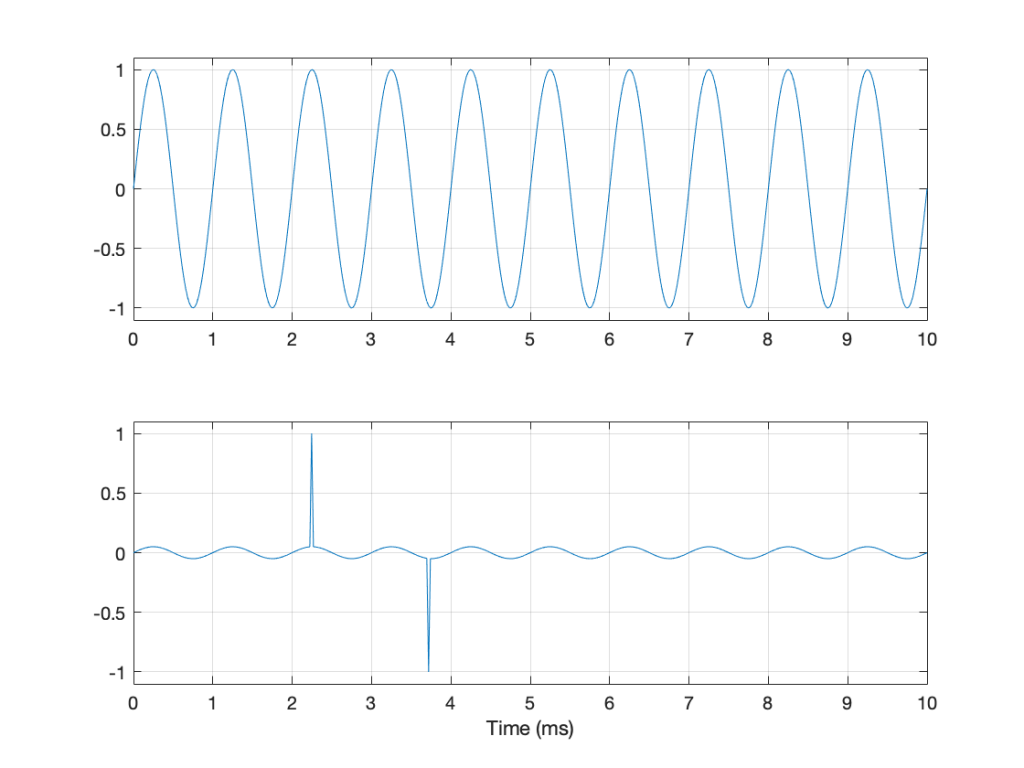

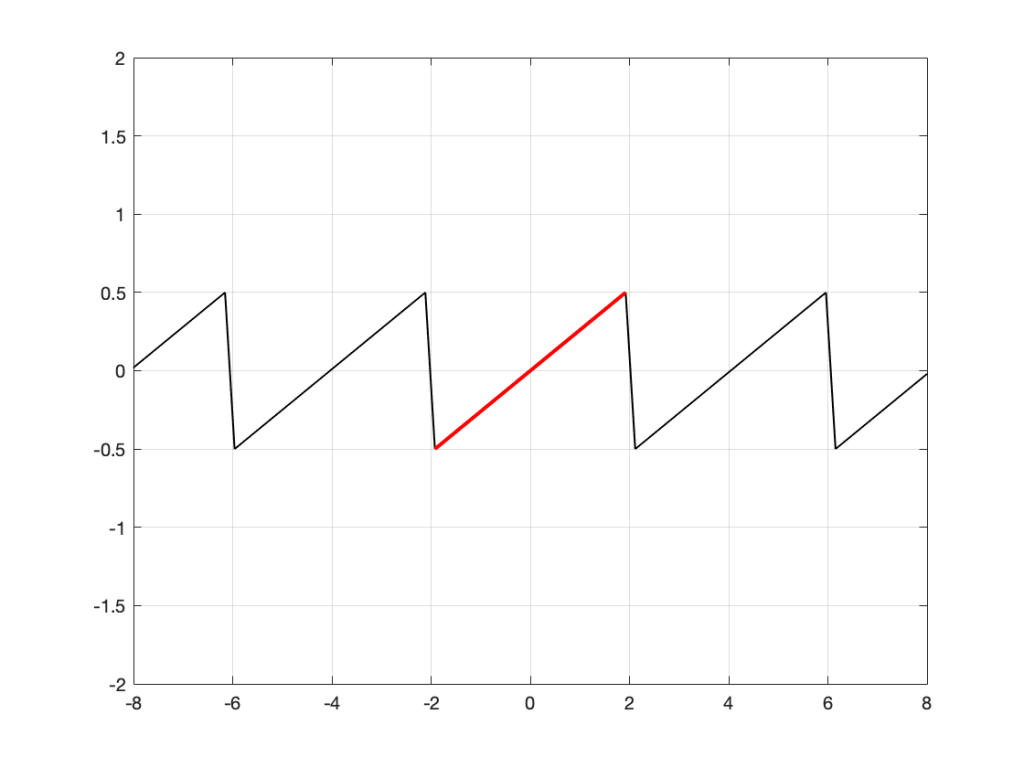

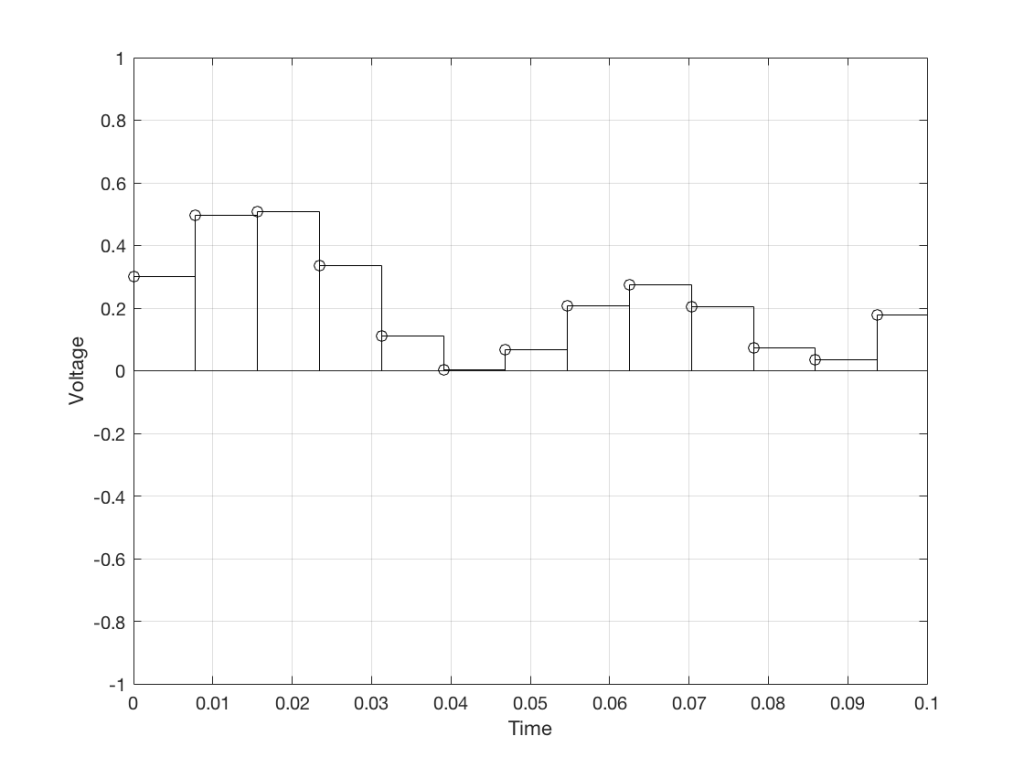

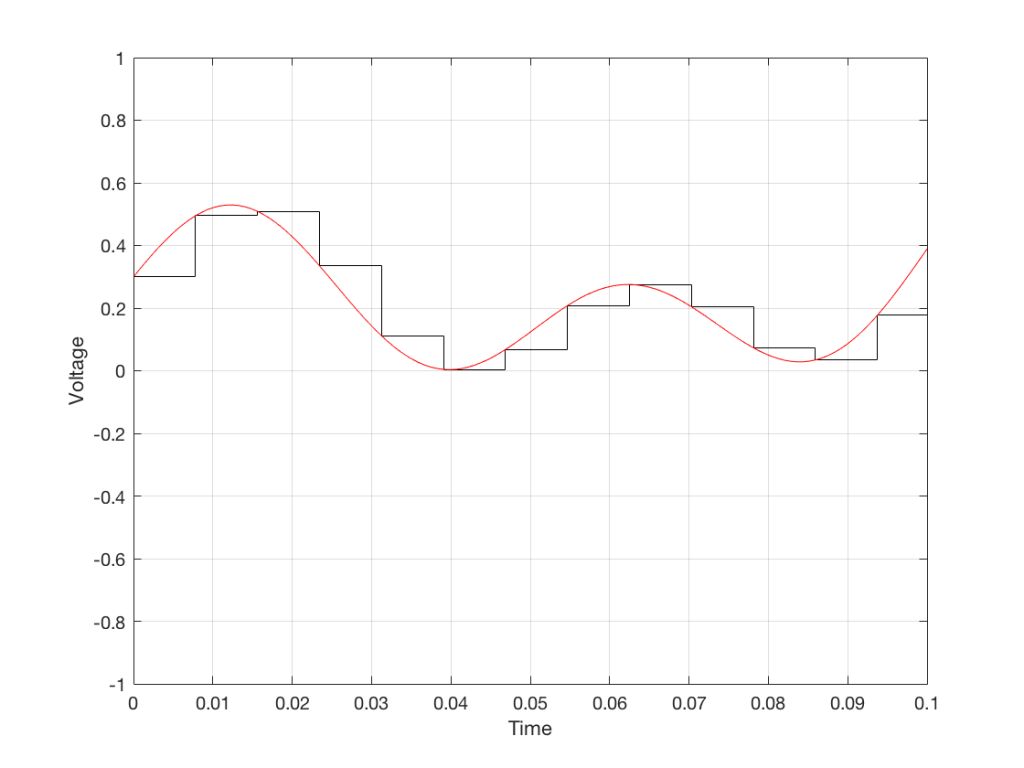

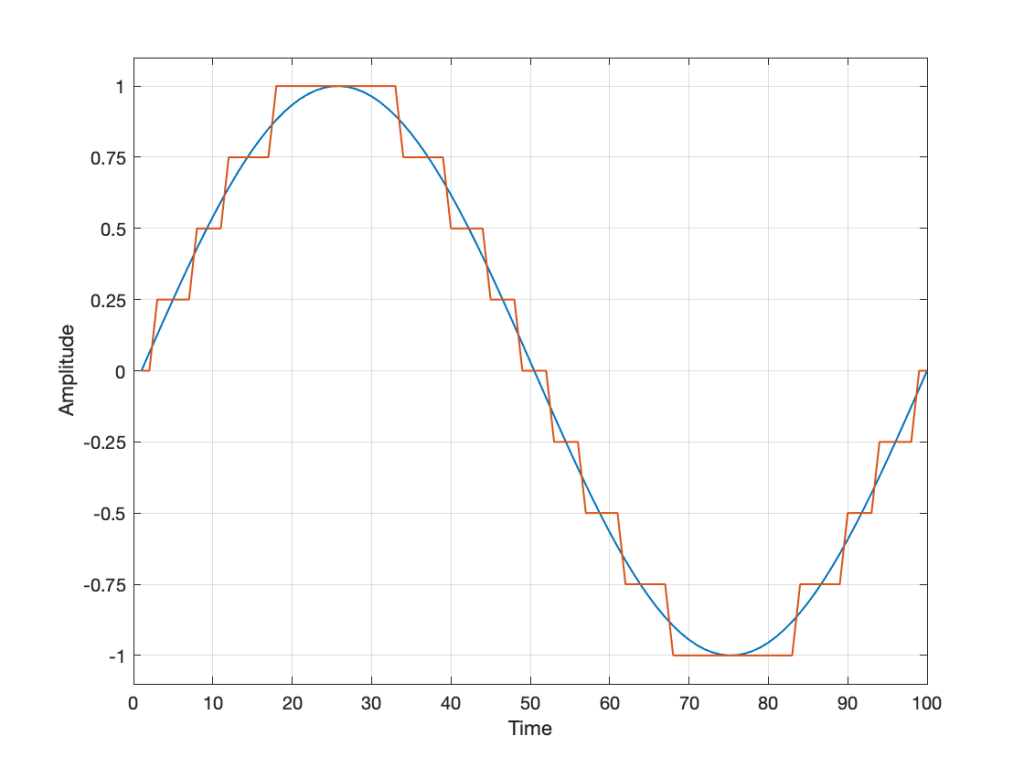

We then make a “staircase” waveform by “holding” those voltages until the next value comes in.

All we need to do then is to use a low-pass filter to smooth out the hard edges of the staircase.

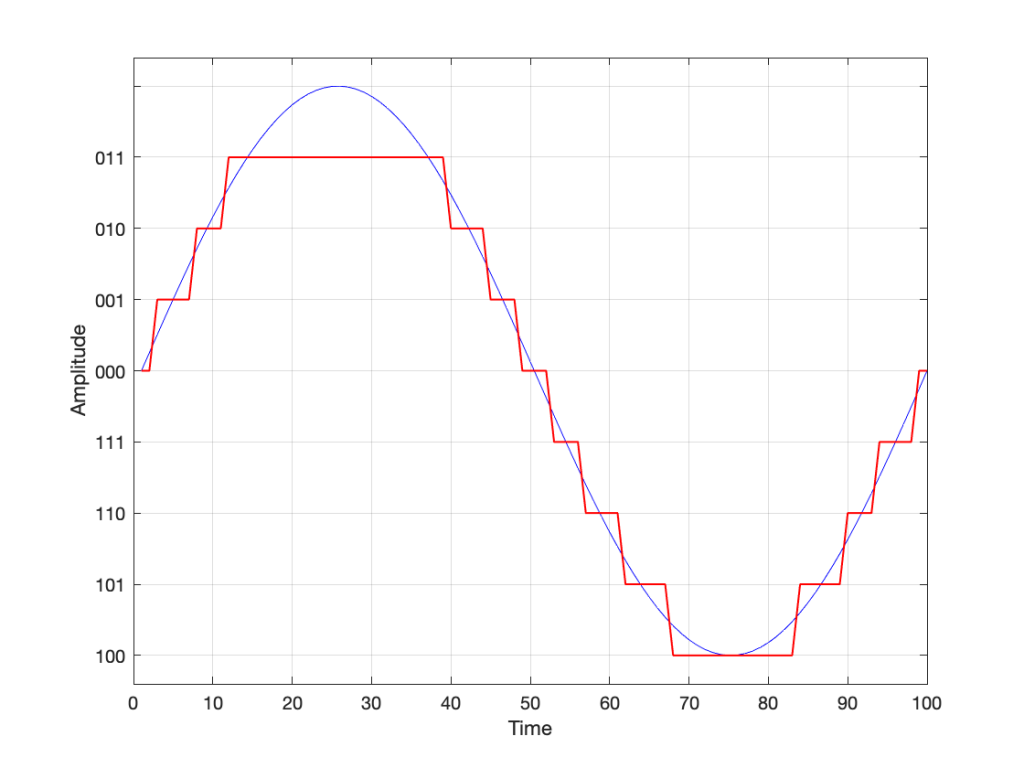

So, in this example, we’ve gone from an analogue signal (the red curve in Figure 3) to a digital signal (the series of numbers), and back to an analogue signal (the red curve in Figure 7).

In some ways, this is a bit like the way a movie works. When you watch a movie, you see a series of still photographs, probably taken at a rate of 24 pictures (or frames) per second. If you play those photos back at the same rate (24 fps or frames per second), you think you see movement. However, this is because your eyes and brain aren’t fast enough to see 24 individual photos per second – so you are fooled into thinking that things on the screen are moving.

However, digital audio is slightly different from film in two ways:

- The sound (equivalent to the movement in the film) is actually happening. It’s not a trick that relies on your ears and brain being too slow.

- If, when you were filming the movie, something were to happen between frames (say, the flash of a gunshot, for example) then it would never be caught on film. This is because the photos are discrete moments in time – and what happens between them is lost. However, if something were to make a very, very short sound between two samples (two measurements) in the digital audio signal – it would not be lost. This is because of something that happens at the beginning of the chain that I haven’t described… yet…

However, there are some “artefacts” (a fancy term for “weird errors”) that are present both in film and in digital audio that we should talk about.

The first is an error that happens when you mess around with the rate at which you take the measurements (called the “sampling rate”) or the photos (called the “frame rate”) – and, more importantly, when you need to worry about this. Let’s say that you make a film at 24 fps. If you play this back at a higher frame rate, then things will move very quickly (like old-fashioned baseball movies…). If you play them back at a lower frame rate, then things move in slow motion. So, for things to look “normal” you have to play the movie at the same rate that it was filmed. However, as long as no one is looking, you can transfer the movie as fast as you like. For example, if you wanted to copy the film, you could set up a movie camera so it was pointing at a movie screen and film the film. As long as the movie on the screen is running in sync with the camera, you can do this at any frame rate you like. But you’ll have to watch the copy at the same frame rate as the original film… (Note that this issue is not something that will come up in this series of postings about high resolution audio)

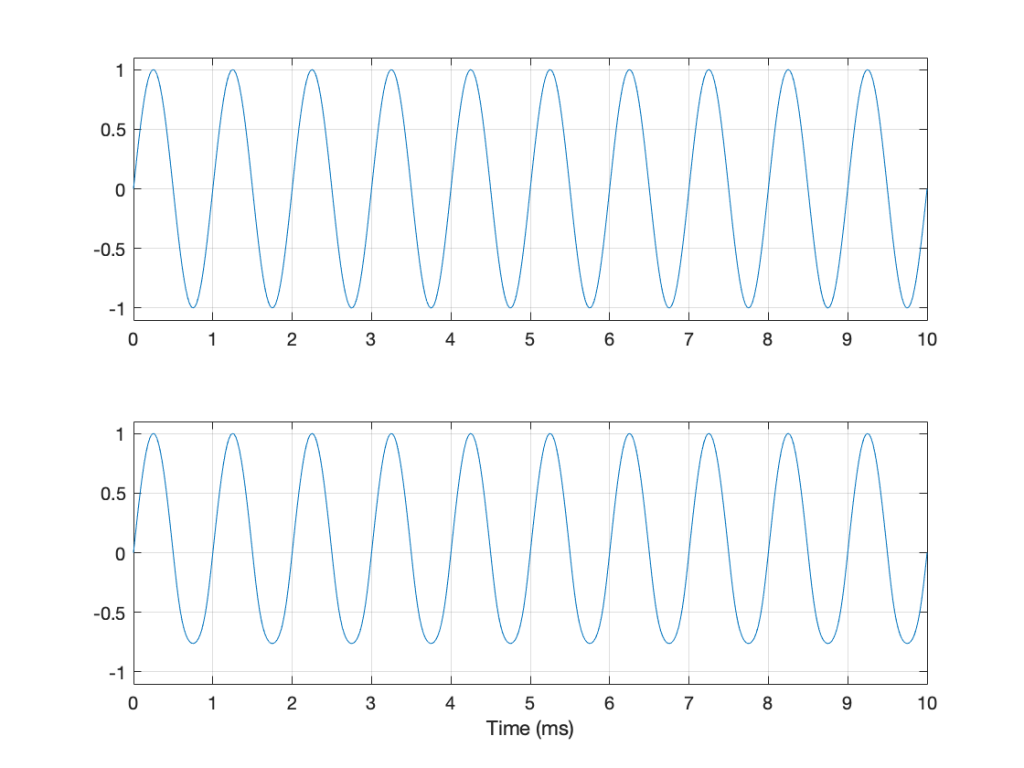

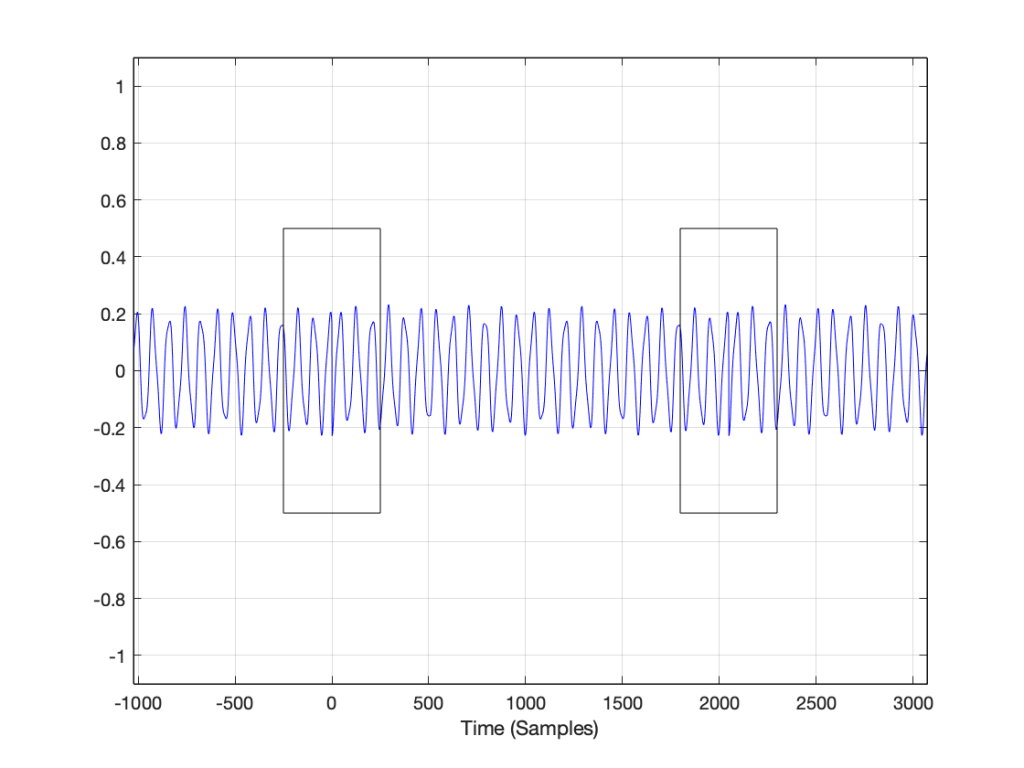

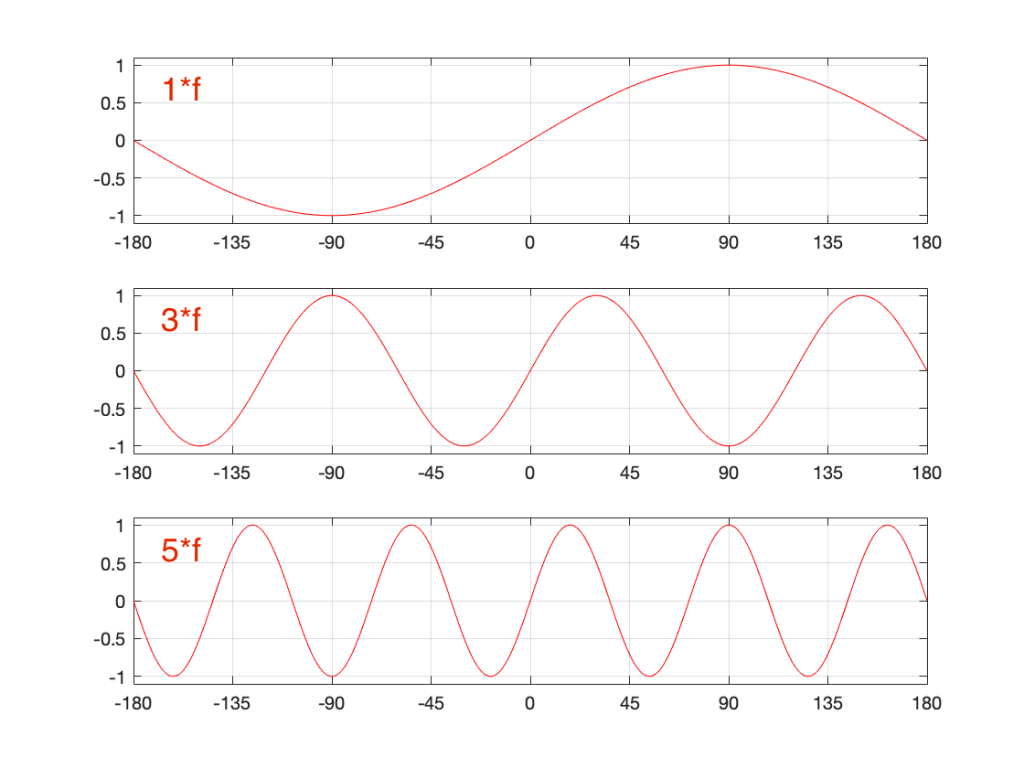

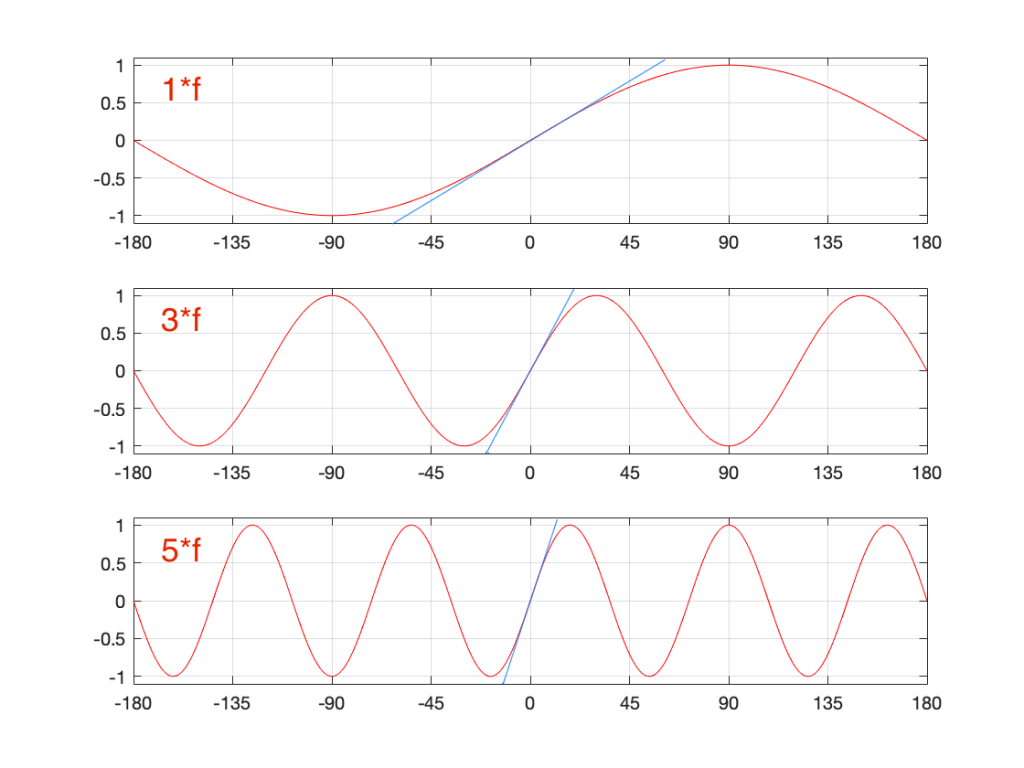

The second is an easy artefact to recognise. If you see a car accelerating from 0 to something fast on film, you’ll see the wheels of the car start to get faster and faster, then, as the car gets faster, the wheels slow down, stop, and then start going backwards… This does not happen in real life (unless you’re in a place lit with flashing lights like fluorescent bulbs or LED’s). I’ll do a posting explaining why this happens – but the thing to remember here is that the speed of the wheel rotation that you see on the film (the one that’s actually captured by the filming…) is not the real rotational speed of the wheel. However, those two rotational speeds are related to each other (and to the frame rate of the film). If you change the real rotational rate or the frame rate, you’ll change the rotational rate in the film. So, we call this effect “aliasing” because it’s a false version (an alias) of the real thing – but it’s always the same alias (assuming you repeat the conditions…) Digital audio can also suffer from aliasing, but in this case, you put in one frequency (which is actually the same as a rotational speed) and you get out another one. This is not the same as harmonic distortion, since the frequency that you get out is due to a relationship between the original frequency and the sampling rate, so the result is almost never a multiple of the input frequency. (We’re going to dig into this a lot deeper through this series of postings about high resolution audio, so if it doesn’t immediately make sense, don’t worry…)

Some important details that I left out…

One of the things I said above was something like “we measure the voltage and store the results” and the example I gave was a nice series of numbers that only had 4 digits after the decimal point. This statement has some implications that we need to discuss.

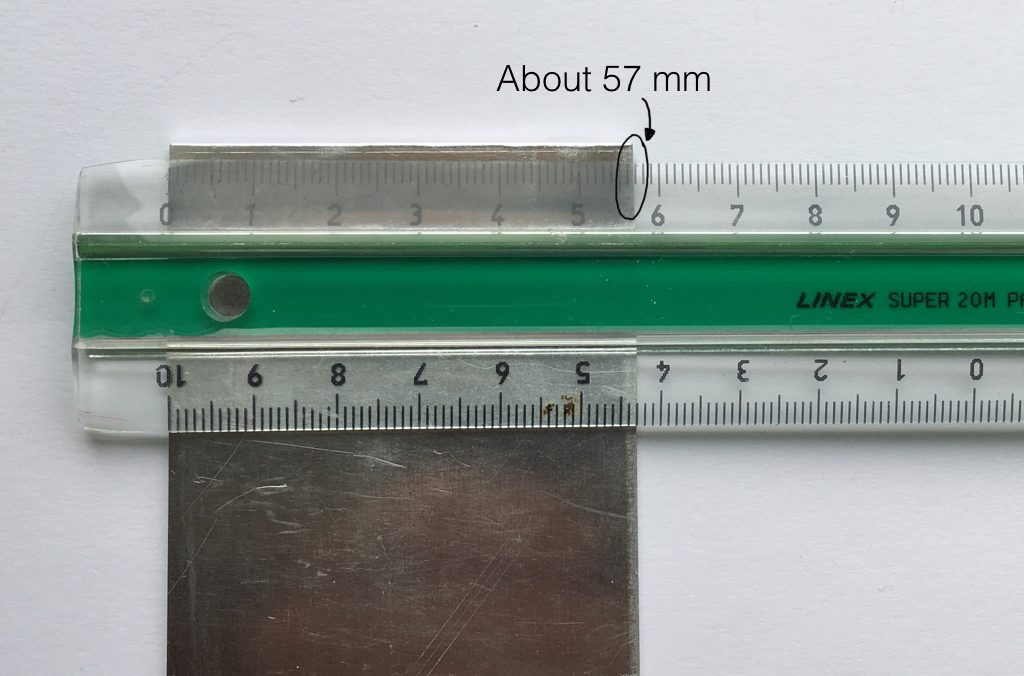

Let’s say that I have a thing that I need to measure. For example, Figure 8 shows a piece of metal, and I want to measure its width.

Using my ruler, I can see that this piece of metal is about 57 mm wide. However, if I were geeky (and I am) I would say that this is not precise enough – and therefore it’s not accurate. The problem is that my ruler is only graduated in millimetres. So, if I try to measure anything that is not exactly an integer number of mm long, I’ll either have to guess (and be wrong) or round the measurement to the nearest millimetre (and be wrong).

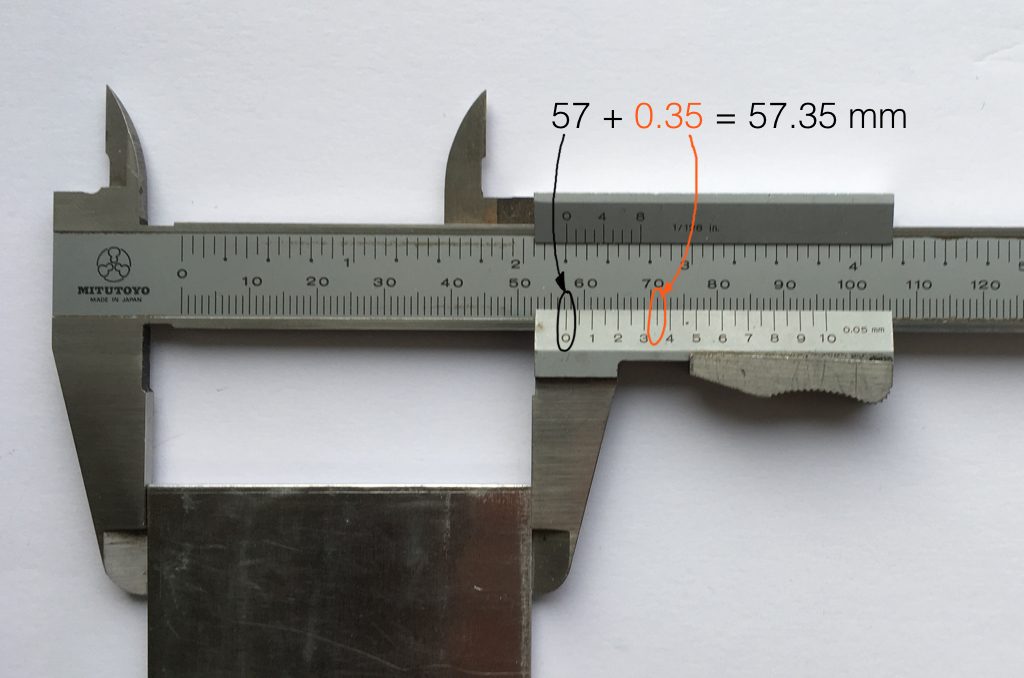

So, if I wanted you to make a piece of metal the same width as my piece of metal, and I used the ruler in Figure 8, we would probably wind up with metal pieces of two different widths. In order to make this better, we need a better ruler – like the one in Figure 9.

Figure 9 shows a vernier caliper (a fancy type of ruler) being used to measure the same piece of metal. The caliper has a resolution of 0.05 mm instead of the 1 mm available on the ruler in Figure 8. So, we can make a much more accurate measurement of the metal because we have a measuring device with a higher precision.

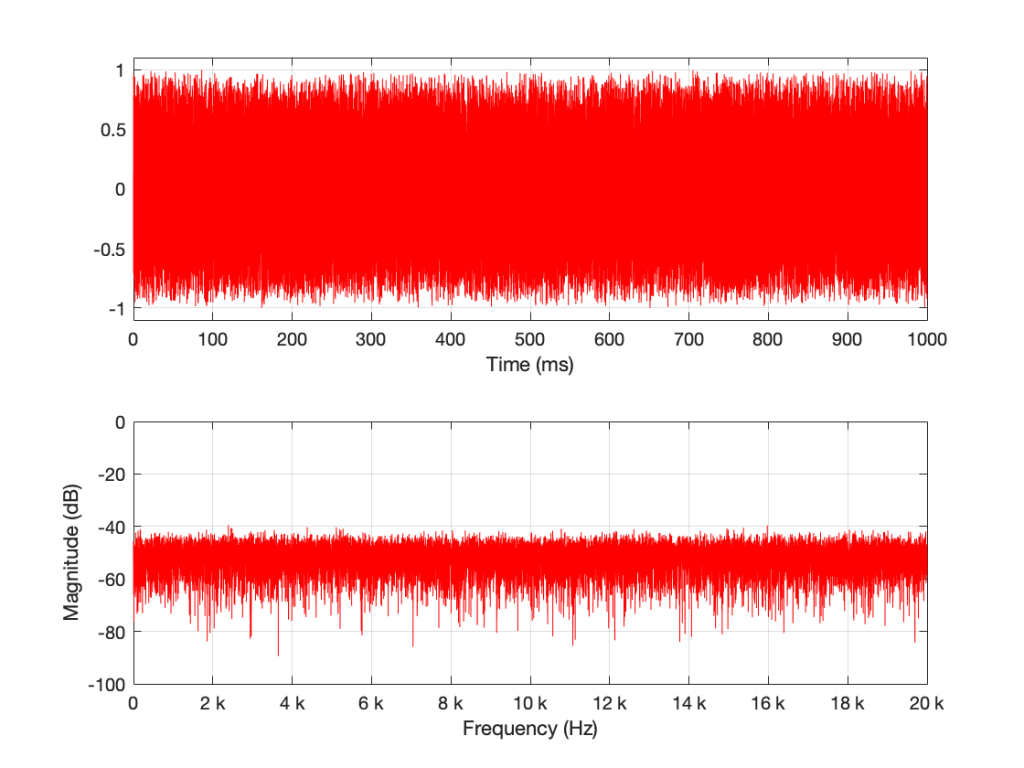

The conversion of a digital audio signal is the same. As I said above, we measure the voltage of the electrical signal, and transmit (or store) the measurement. The question is: how accurate and precise is your measurement? As we saw above, this is (partly) determined by how many digits are in the number that you use when you “write down” the measurement.

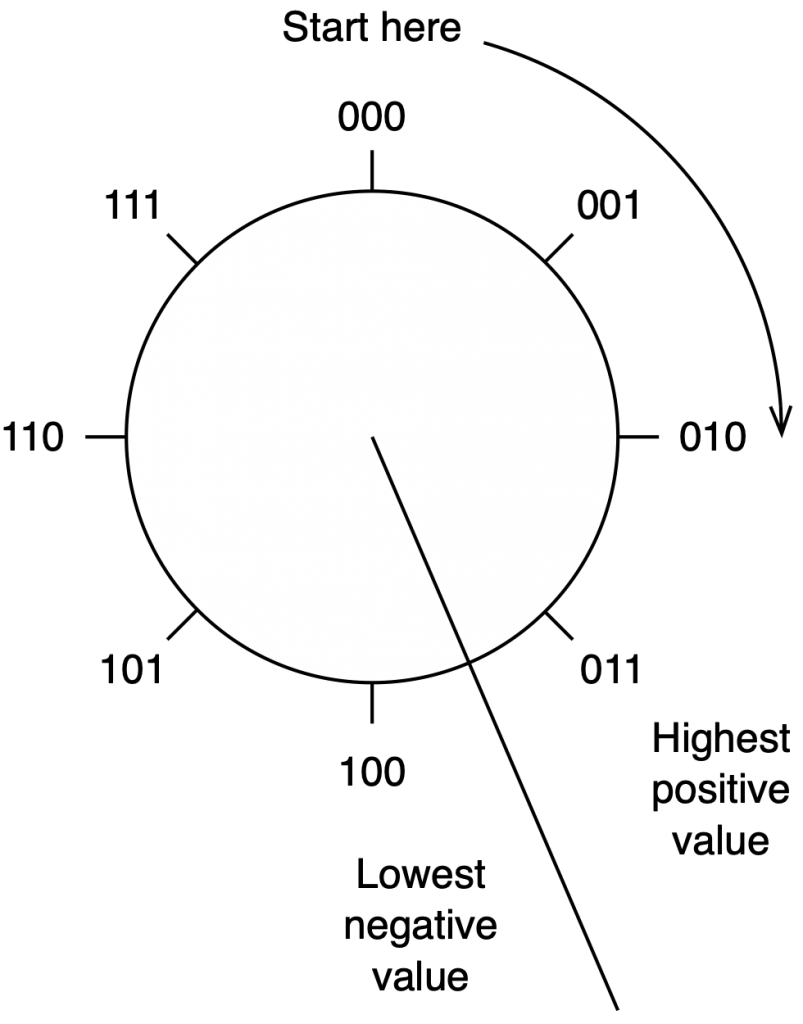

Since the voltage measurements in digital audio are recorded in binary rather than decimal (we use 0 and 1 to write down the number instead of 0 up to 9) then we use Binary digITS – or “bits” instead of decimal digits (which are not called “dits”). The number of bits we have in the number that we write down (partly) determines the precision of the measurement of the voltage – and therefore (possibly), our accuracy…

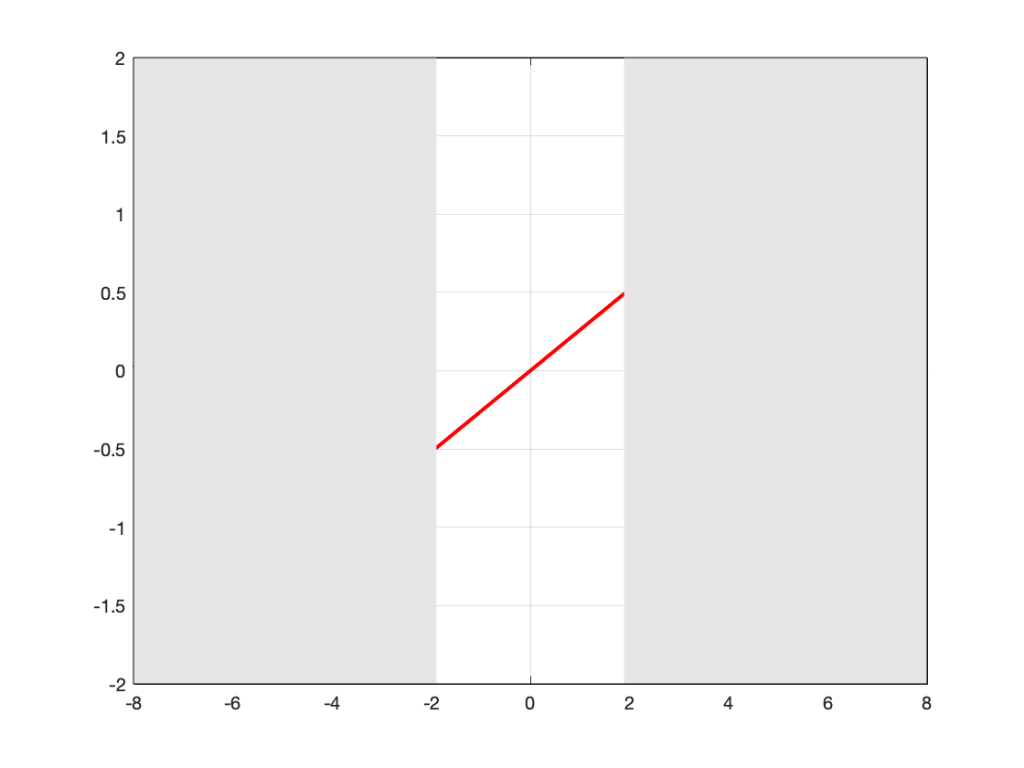

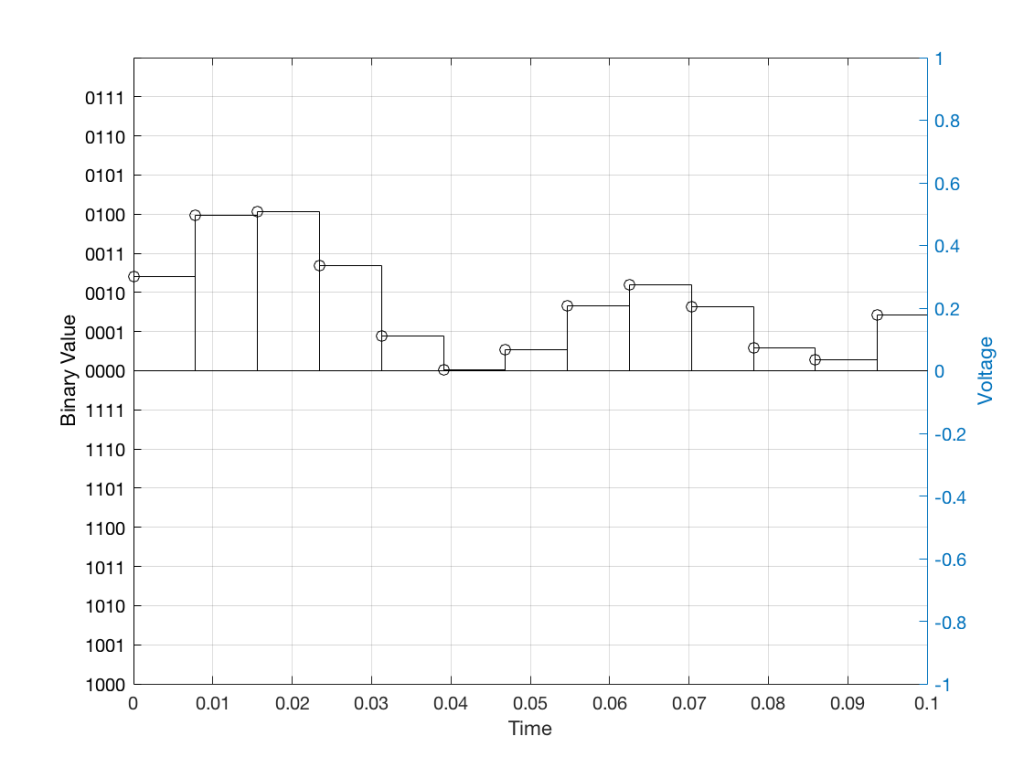

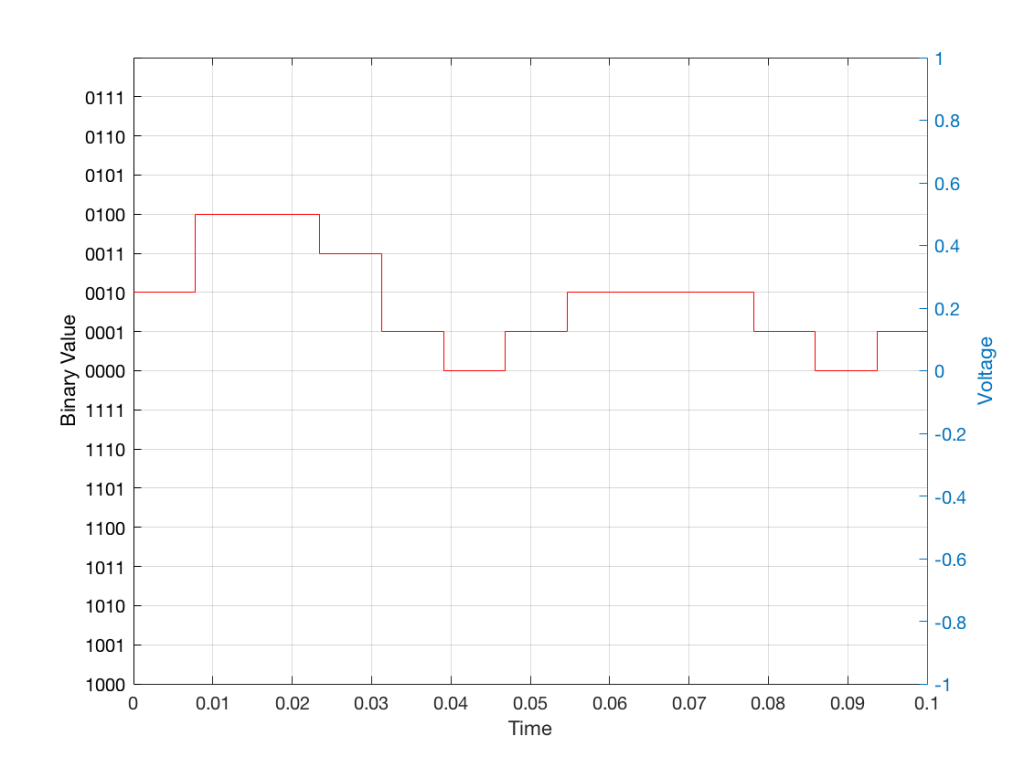

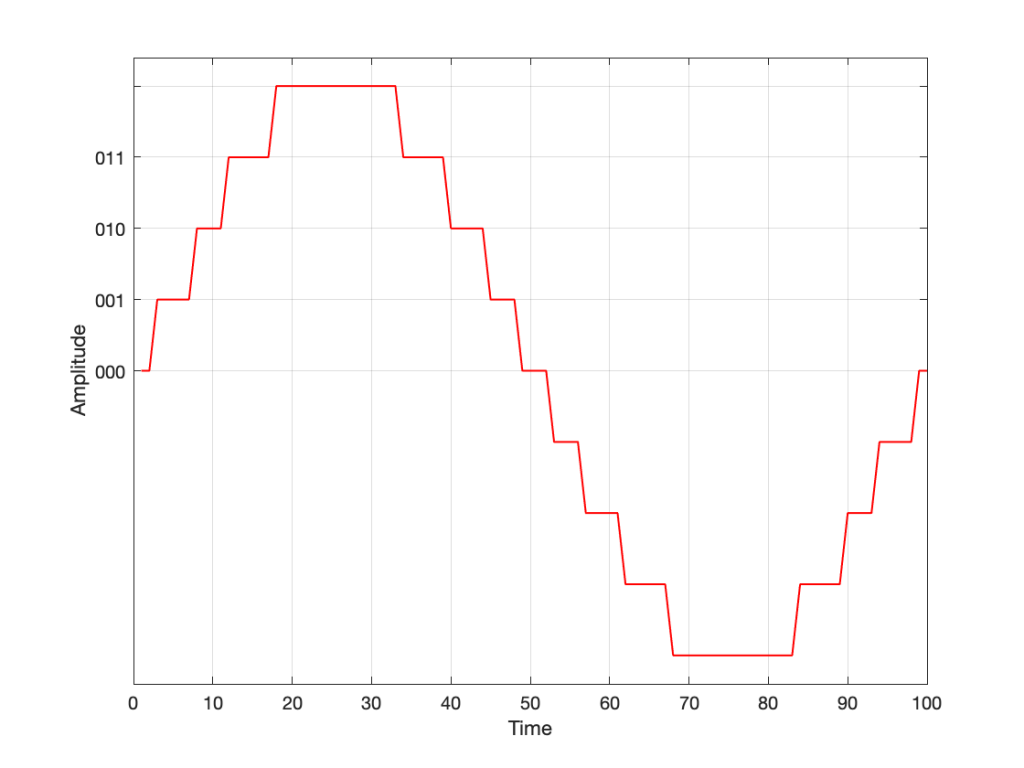

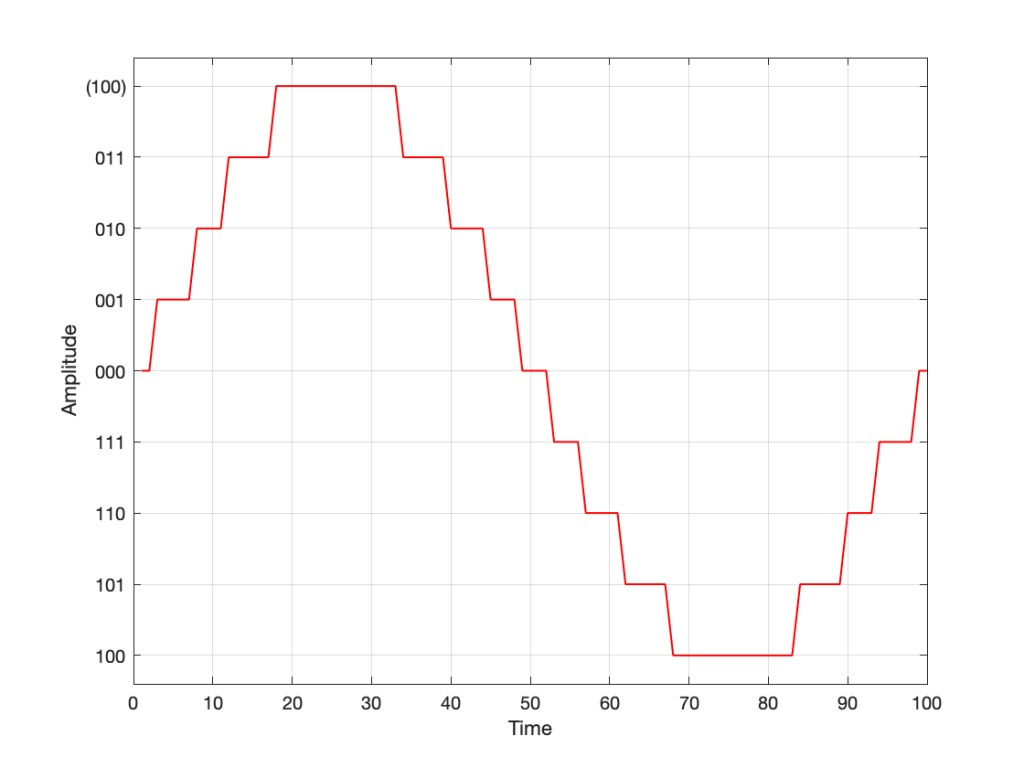

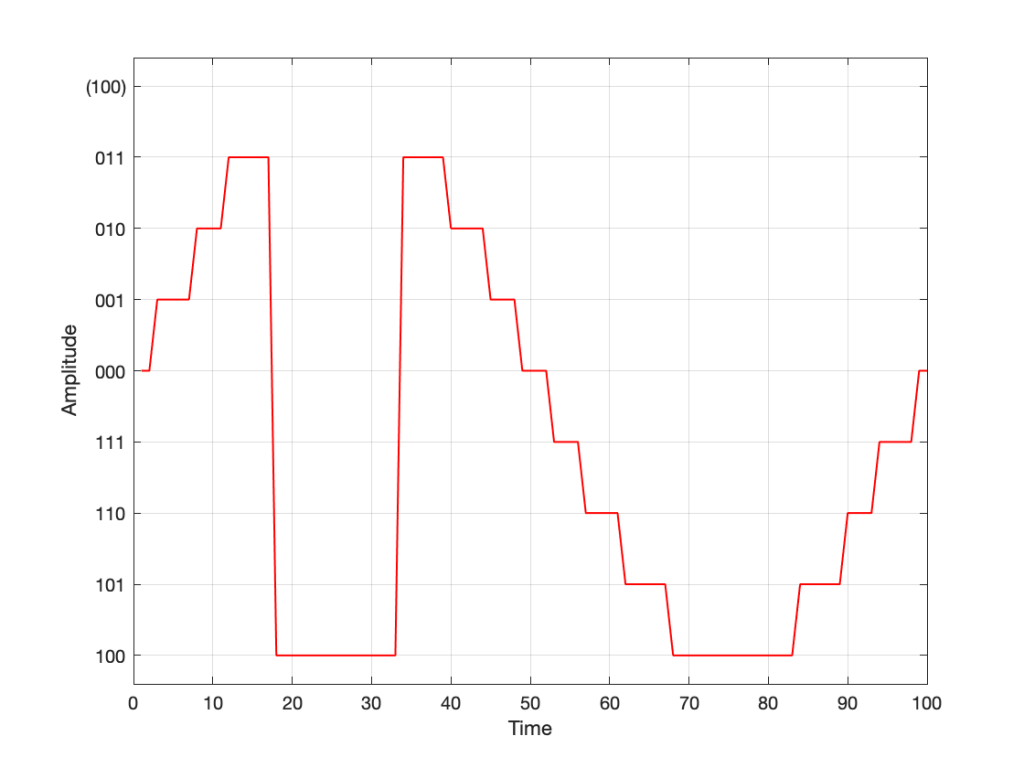

Just like the example of the ruler in Figure 8, above, we have a limited resolution in our measurement. For example, if we had only 4 bits to work with then the waveform in 4 – the one we have to measure – would be measured with the “ruler” shown on the left side of Figure 10, below.

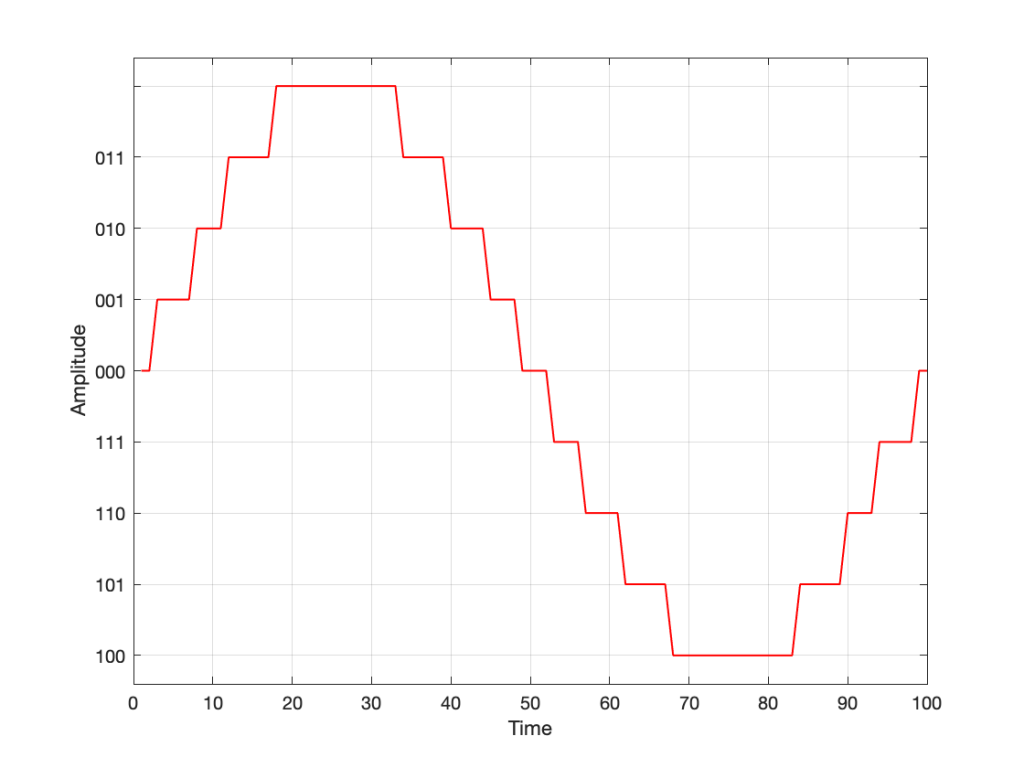

When we do this, we have to round off the value to the nearest “tick” on our ruler, as shown in Figure 11.

Using this “ruler” which gives a write-down-able “quantity” to the measurement, we get the following values for the red staircase:

0010

0100

0100

0011

0001

0000

0001

0010

0010

0010

0001

0000

0001

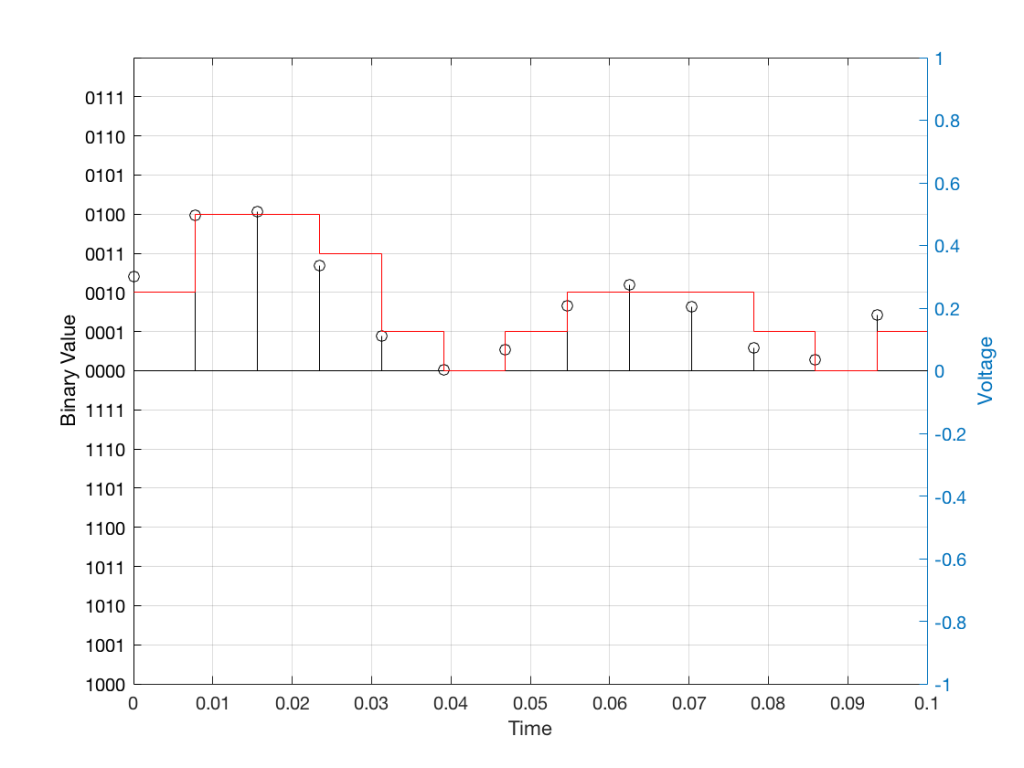

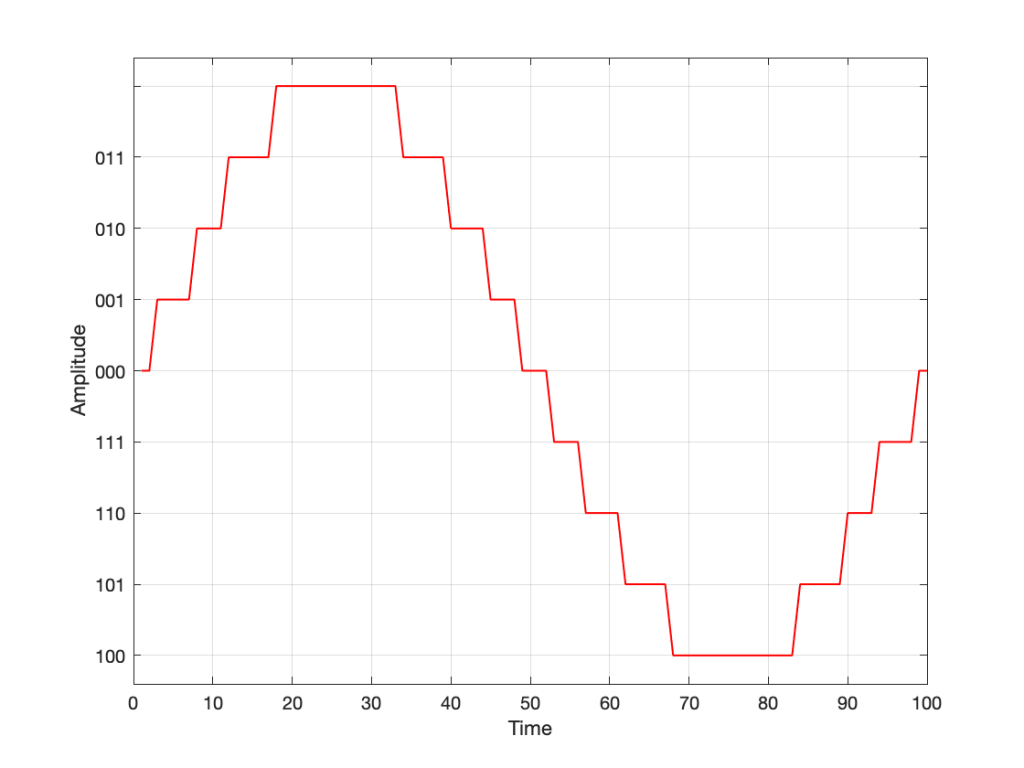

When we “play these back” we get the staircase again, shown in Figure 12.

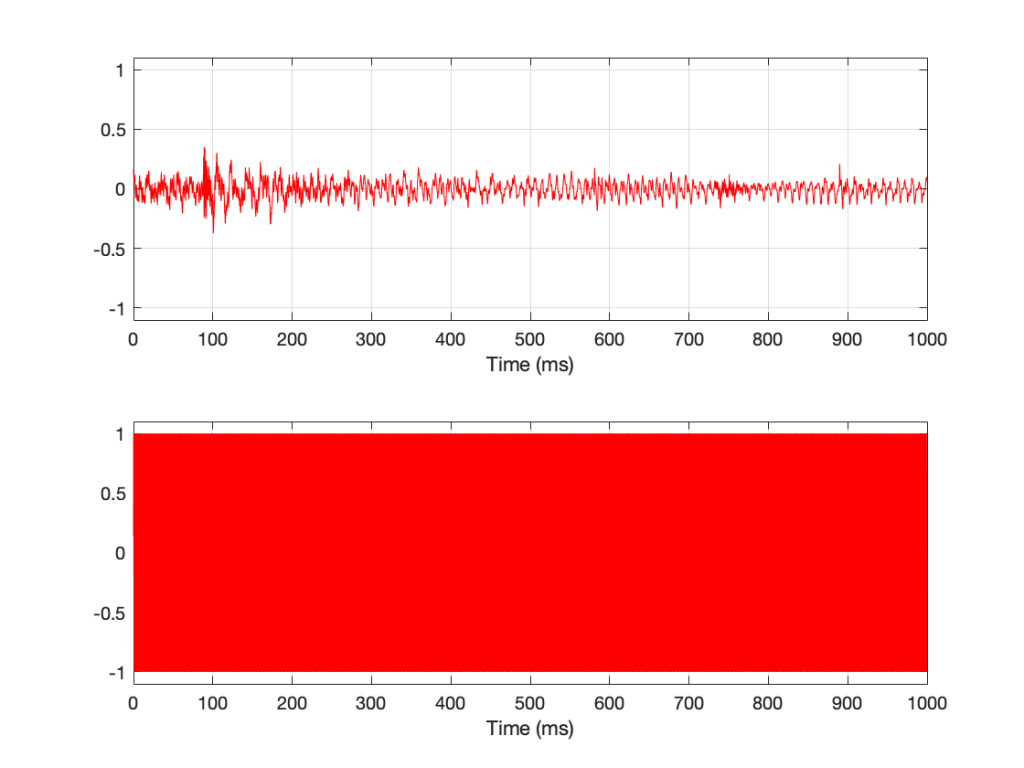

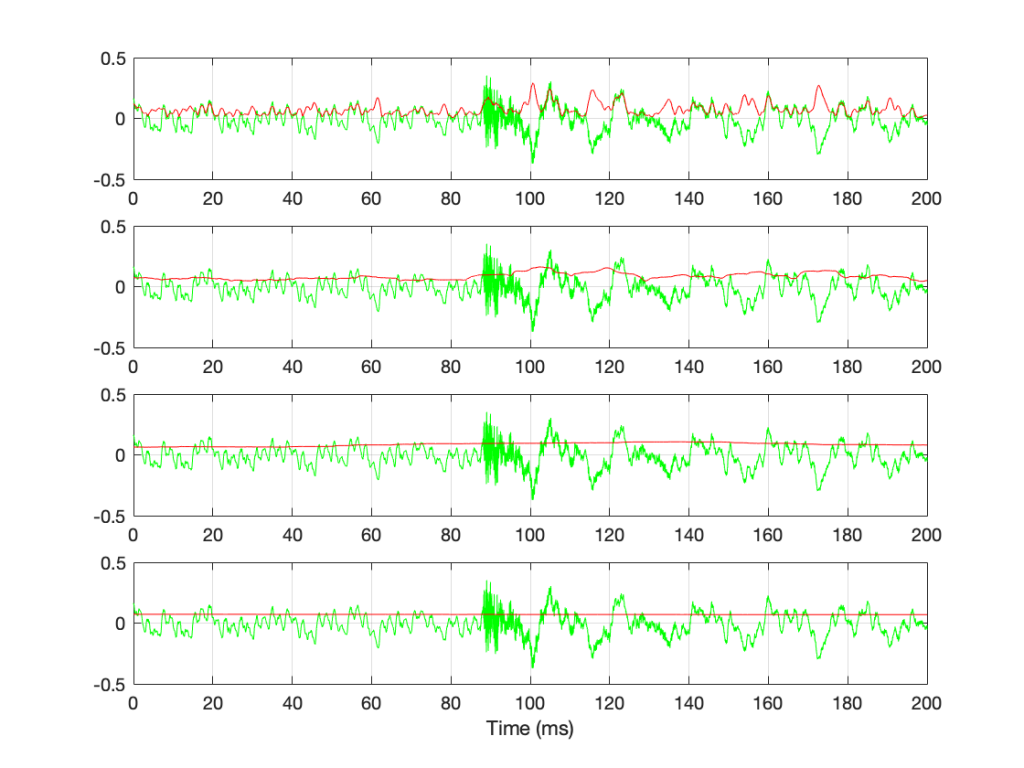

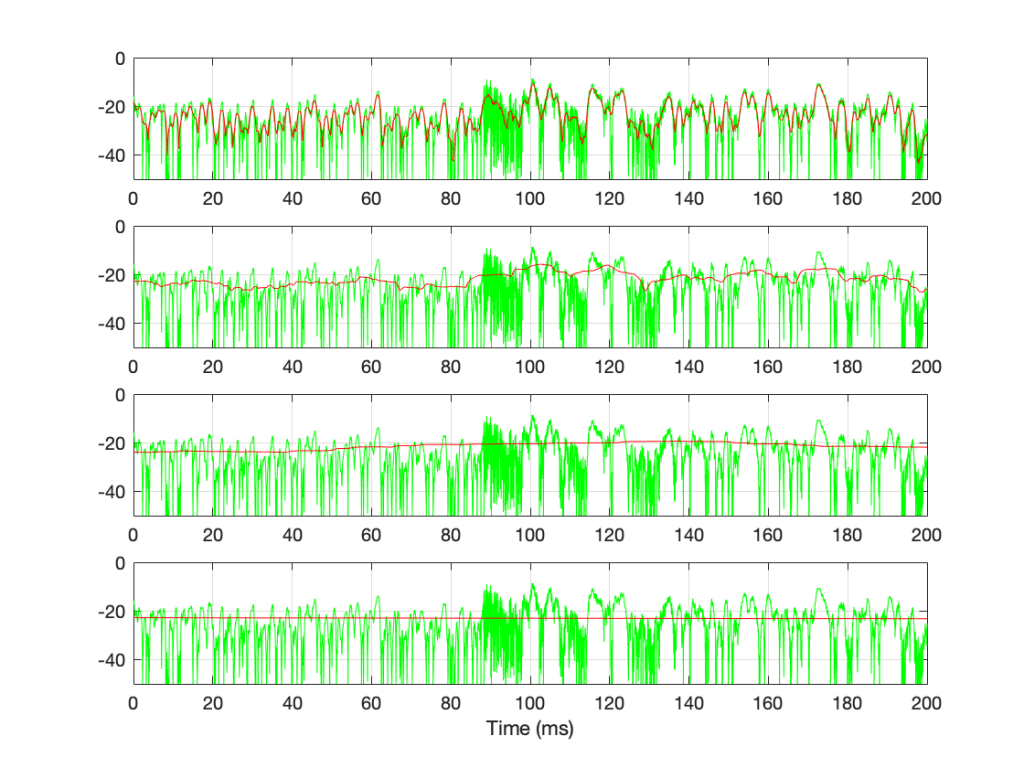

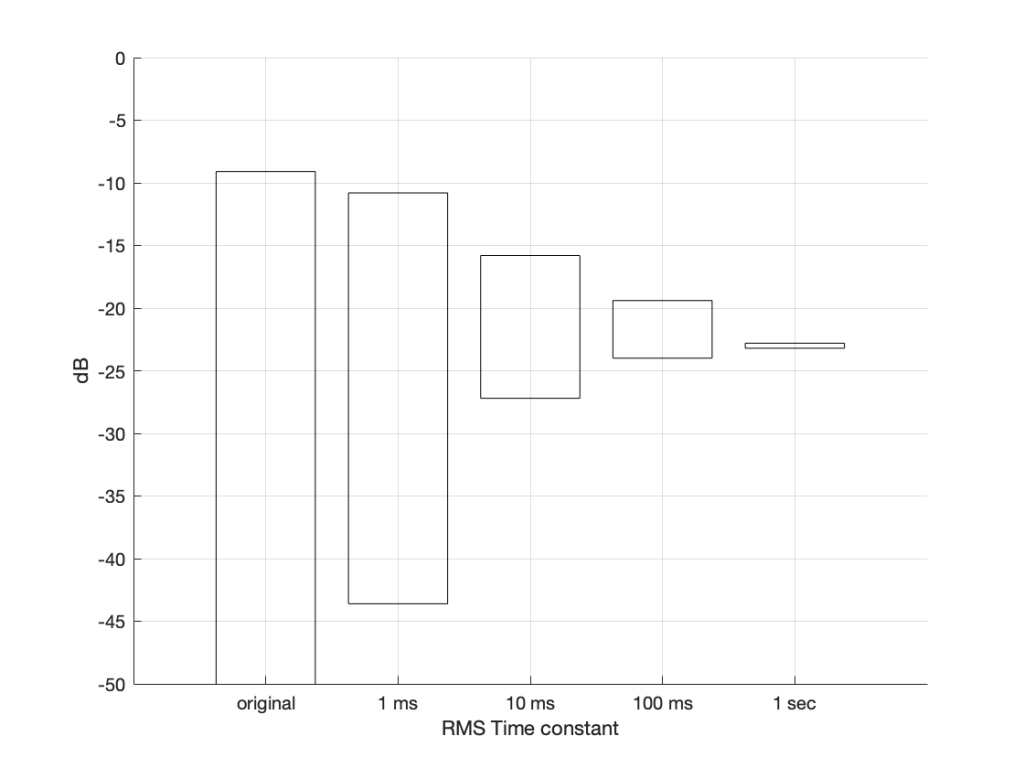

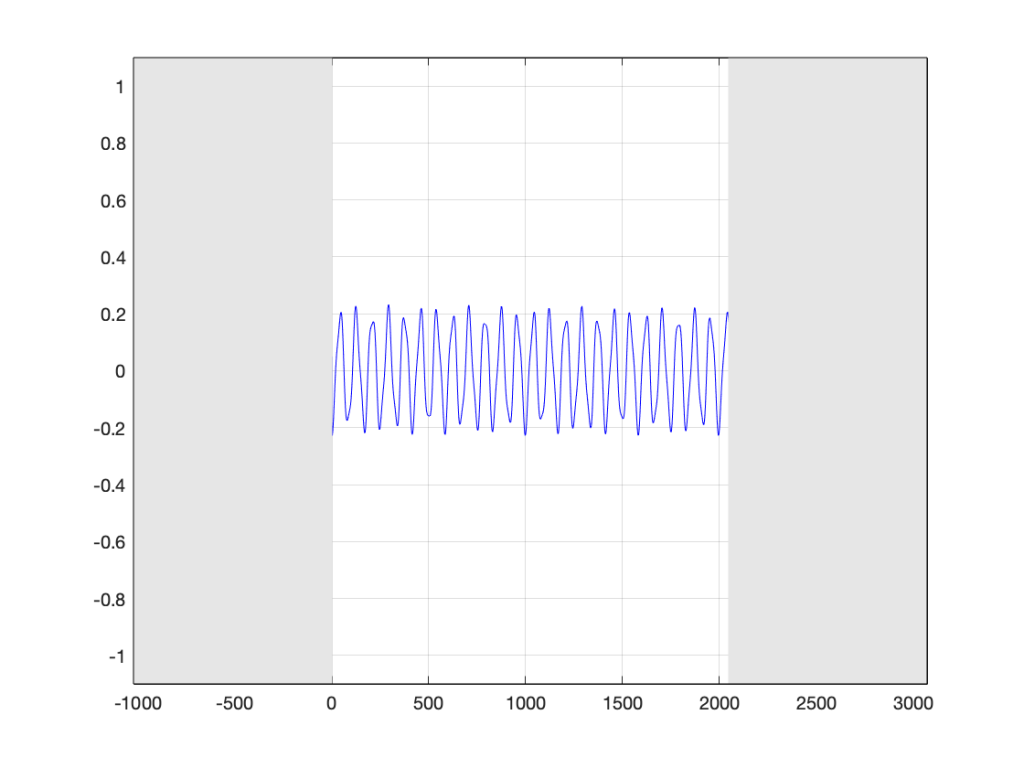

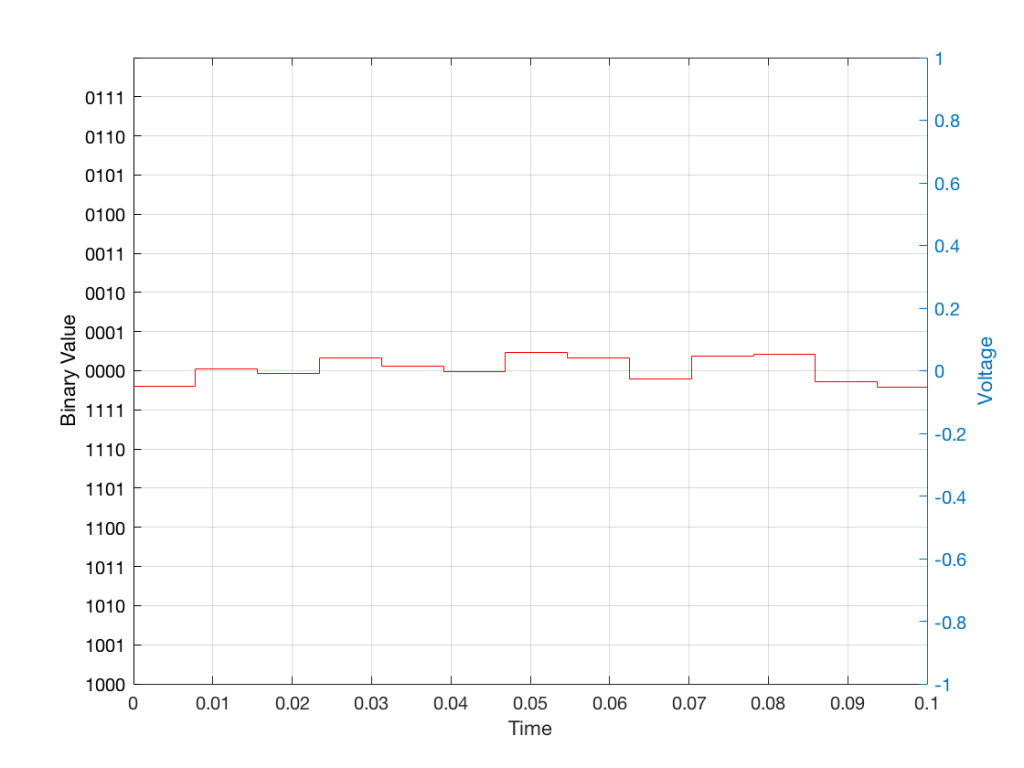

Of course, this means that, by rounding off the values, we have introduced an error in the system (just like the measurement in Figure 8 has a bigger error than the one in Figure 9). We can calculate this error if we just subtract the original signal from the output signal (in other words, Figure 12 minus Figure 10) to get Figure 13.

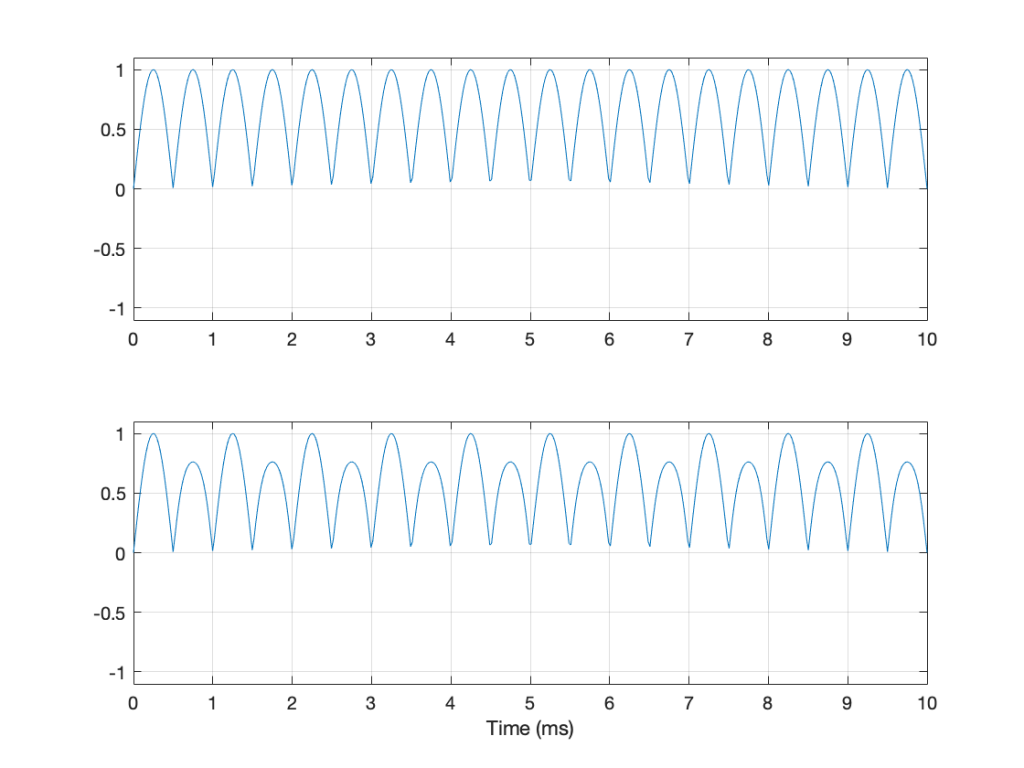

In order to improve our accuracy of the measurement, we have to increase the precision of the values. We can do this by adding an extra digit (or bit) to the number that we use to record the value.

If we were using decimal numbers (0-9) then adding an extra digit to the number would give us 10 times as many possibilities. (For example, if we were using 4 digits after the decimal in the example at the start of this posting, we have a total of 10,000 possible values – 0.0000 to 0.9999. If we add one more digit, we increase the resolution to 100,000 possible values – 0.00000 to 0.99999 ).

In binary, adding one extra digit gives us twice as many “ticks” on the ruler. So, using 4 bits gives us 16 possible values. Increasing to 5 bits gives us 32 possible values.

If you’re listening to a CD, then the individual measurements of each voltage – the “sample values” – are stored with 16 bits, which means that we have 65,536 possible values to pick from.

Remember that this means that we have more “ticks” on our ruler – but we don’t necessarily increase its range. So, for example, we’re still measuring a voltage from -1 V to 1 V – we just have more and more resolution with which we can do that measurement.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[Q_{rbj} = \frac{Q_{z} }{ \sqrt{10^\frac{\lvert G_{dB} \rvert }{20}}}\]](http://www.tonmeister.ca/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9d5c89c7773d38d1f6d2801064f2fd8b_l3.png)