This posting is just wrapping up the series. No more plots… I promise.

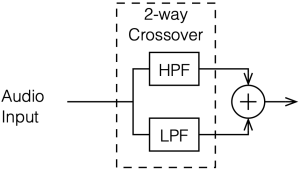

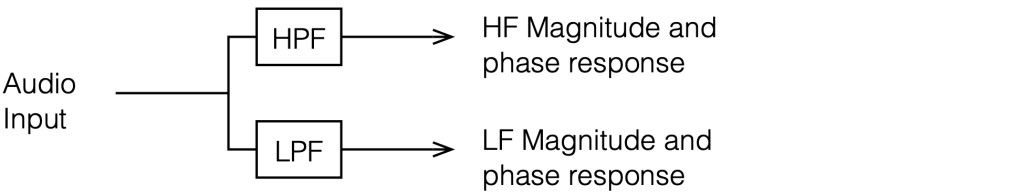

Of course, this entire series has focused the “greatest hits” of the crossover club which is a limited number of crossover types. There are many other options that I haven’t talked about, but my point was not to explain how to choose and design a crossover for a loudspeaker for the DIY’er. It was to

- give a primer on some of the things to consider when implementing a crossover

- instil instinctive suspicion and doubt when you read an advertisement (or a comment on the Internet) that says something like “this loudspeaker is good (or bad) because it has THIS kind of crossover.”

There are plenty of things that I didn’t (and won’t) talk about, such as:

- Crossovers for loudspeakers with more than two outputs

- Other crossover designs. For example, as a start, search for:

- Malcom Hawksford Asymmetrical Crossover

- Malcom Hawksford discussion of stochastic crossovers associated with DMLs

- Linkwitz’s page on crossover design

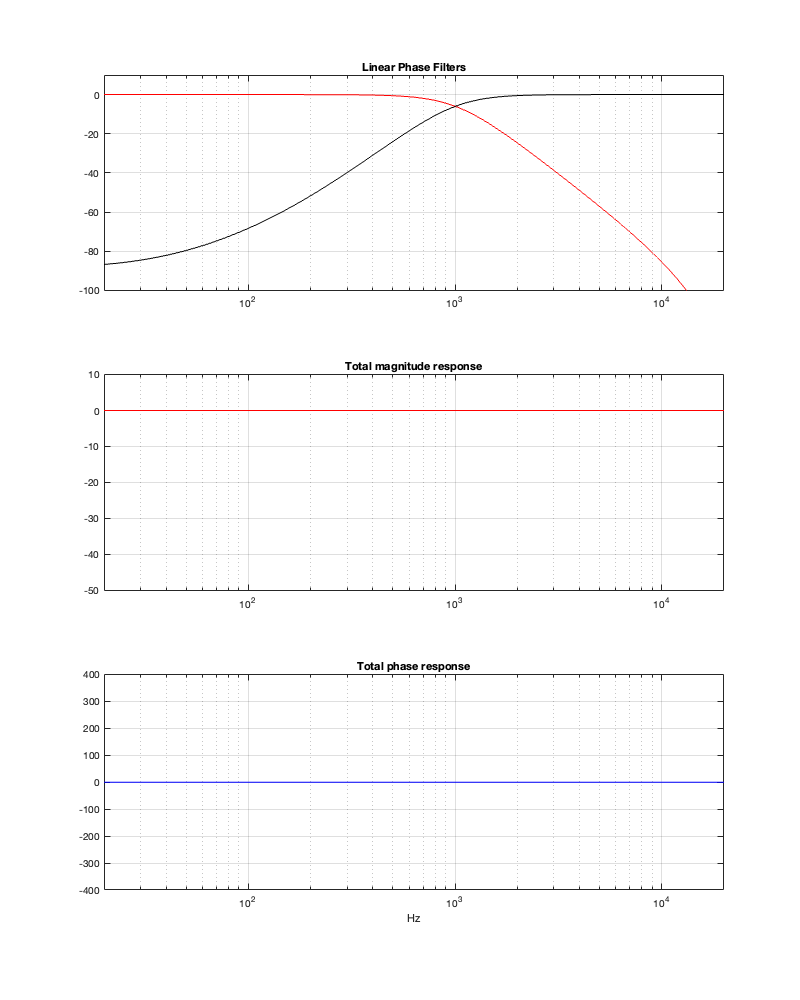

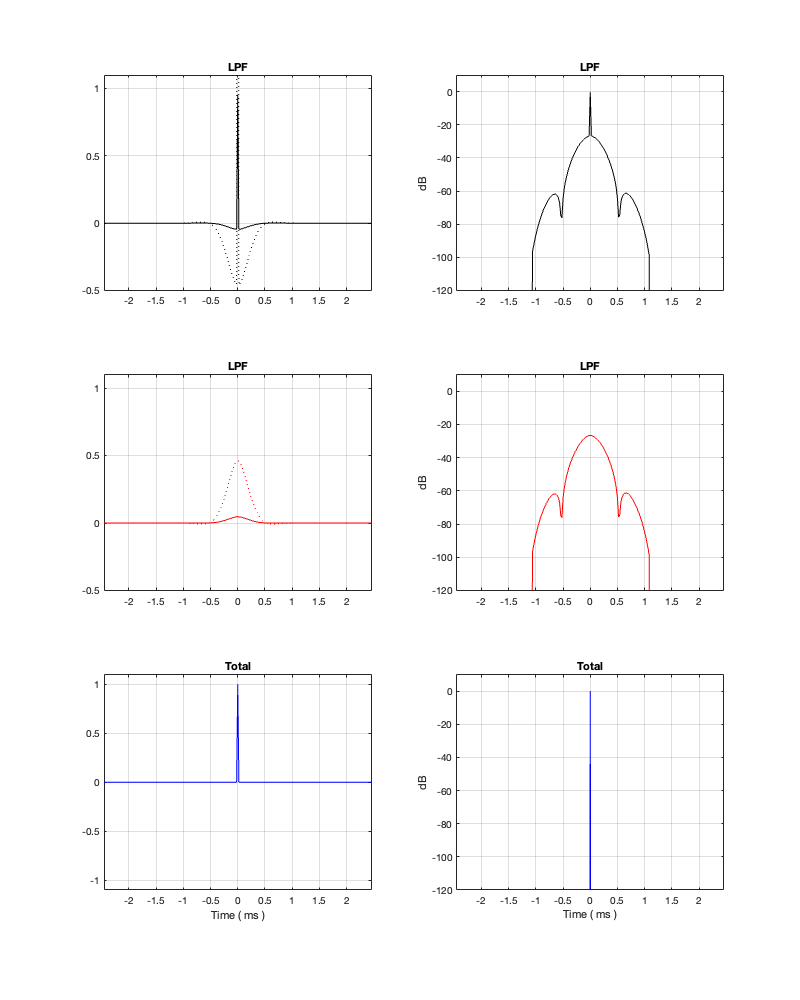

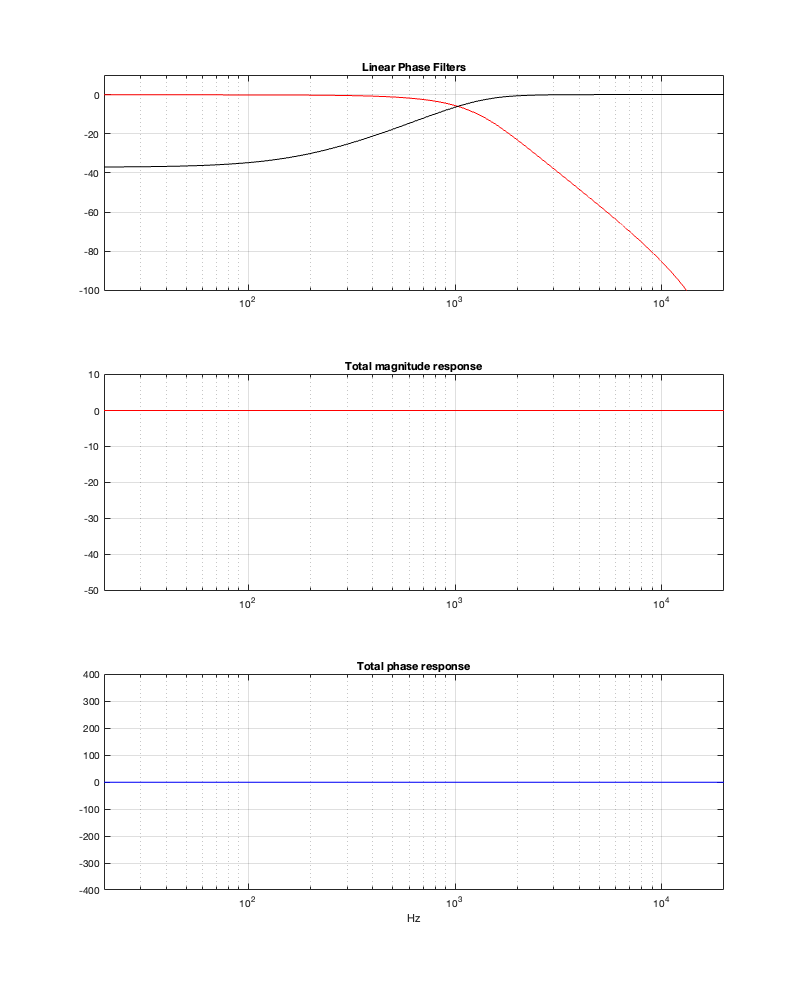

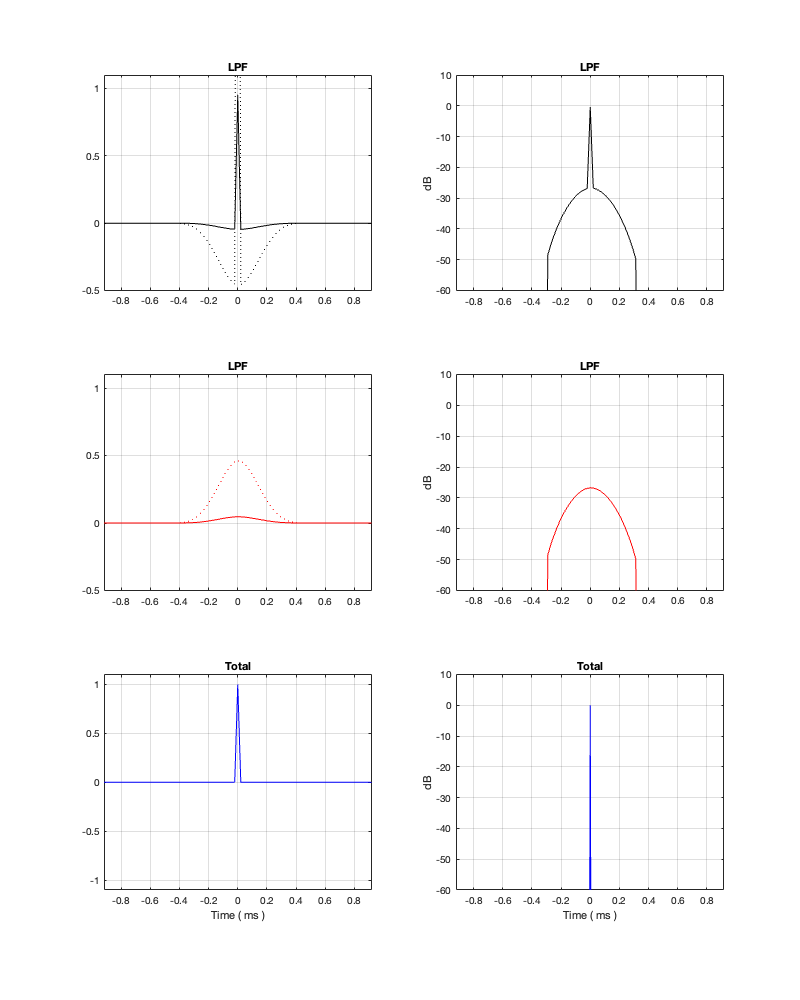

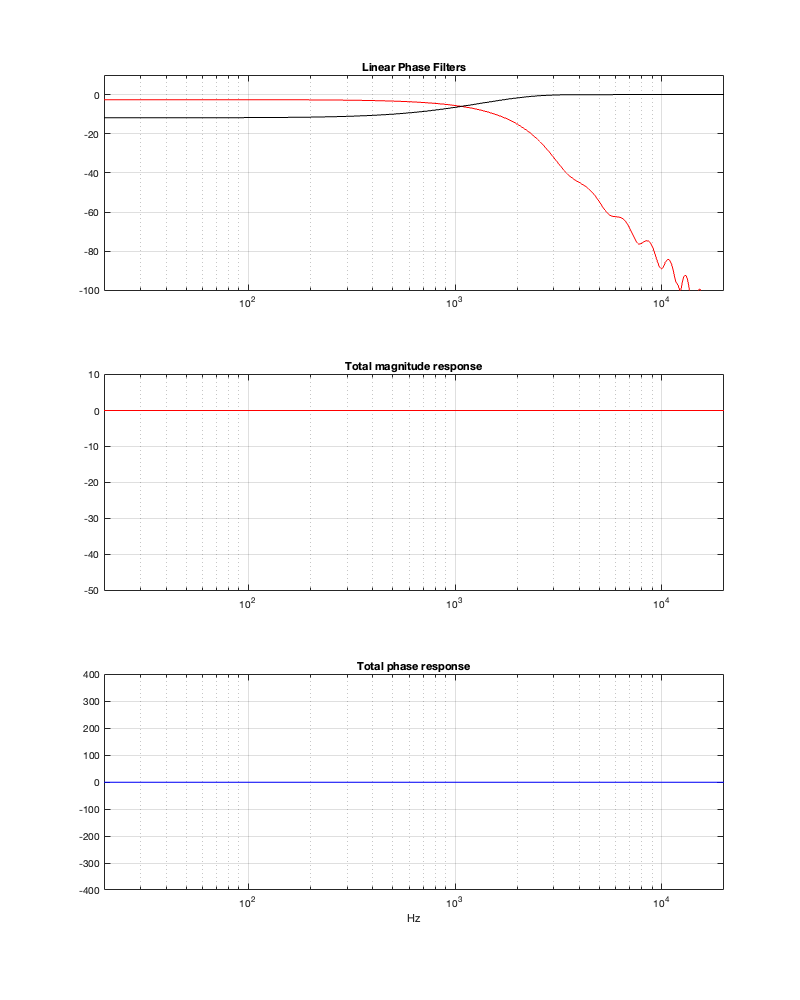

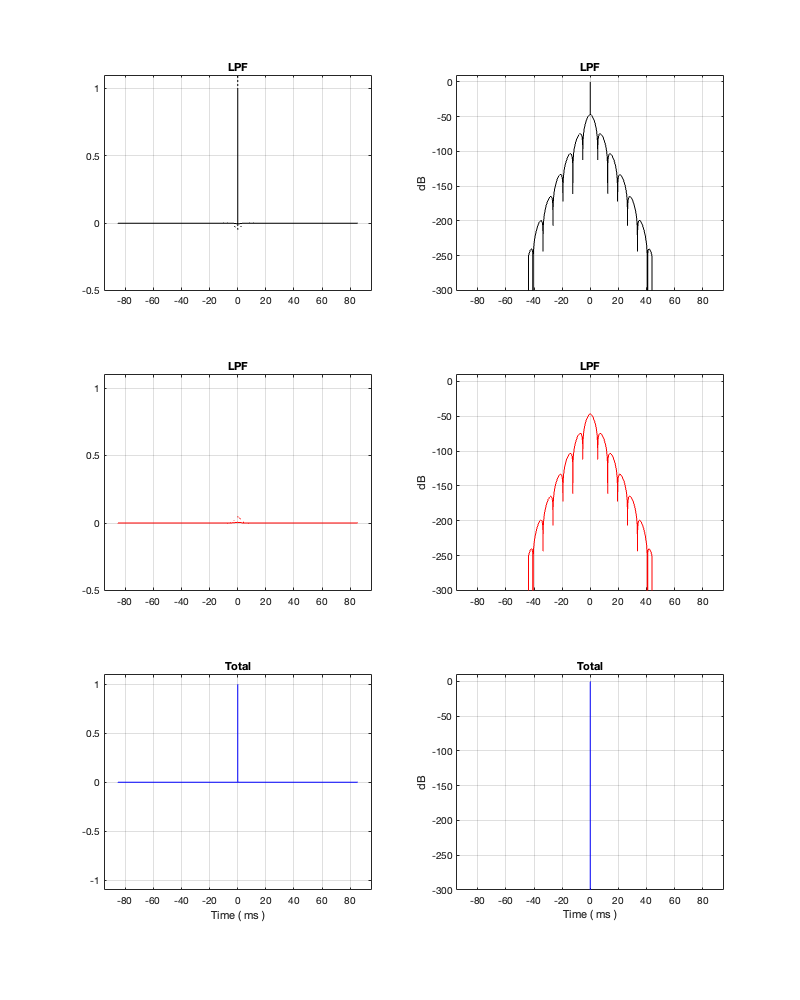

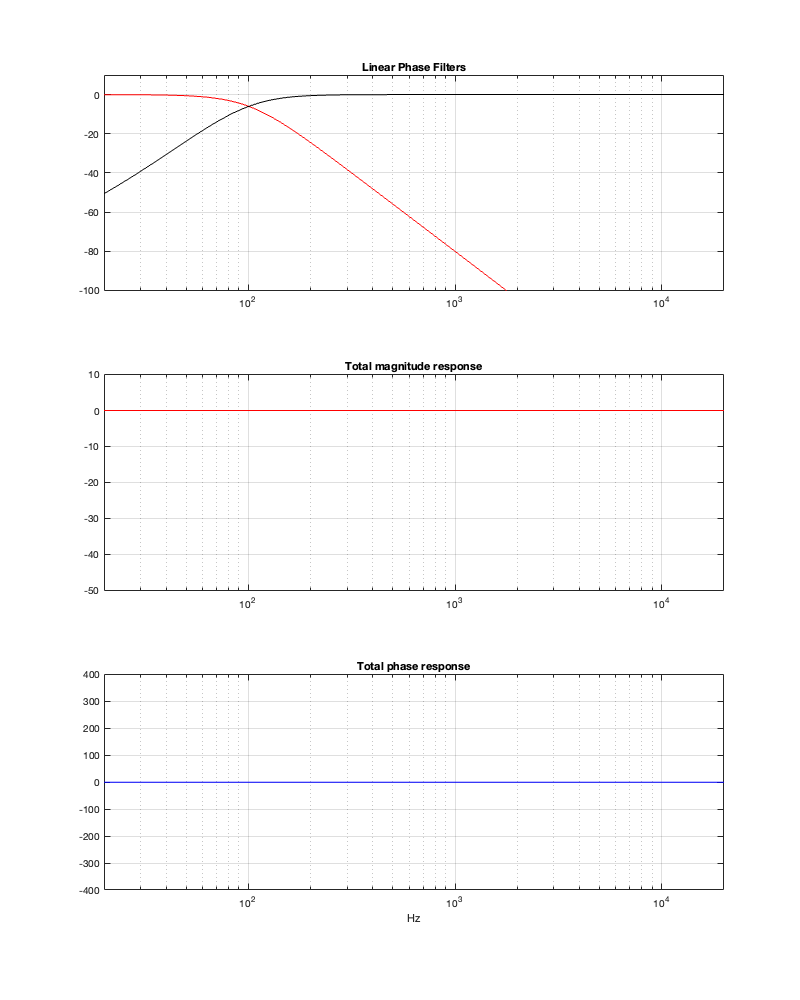

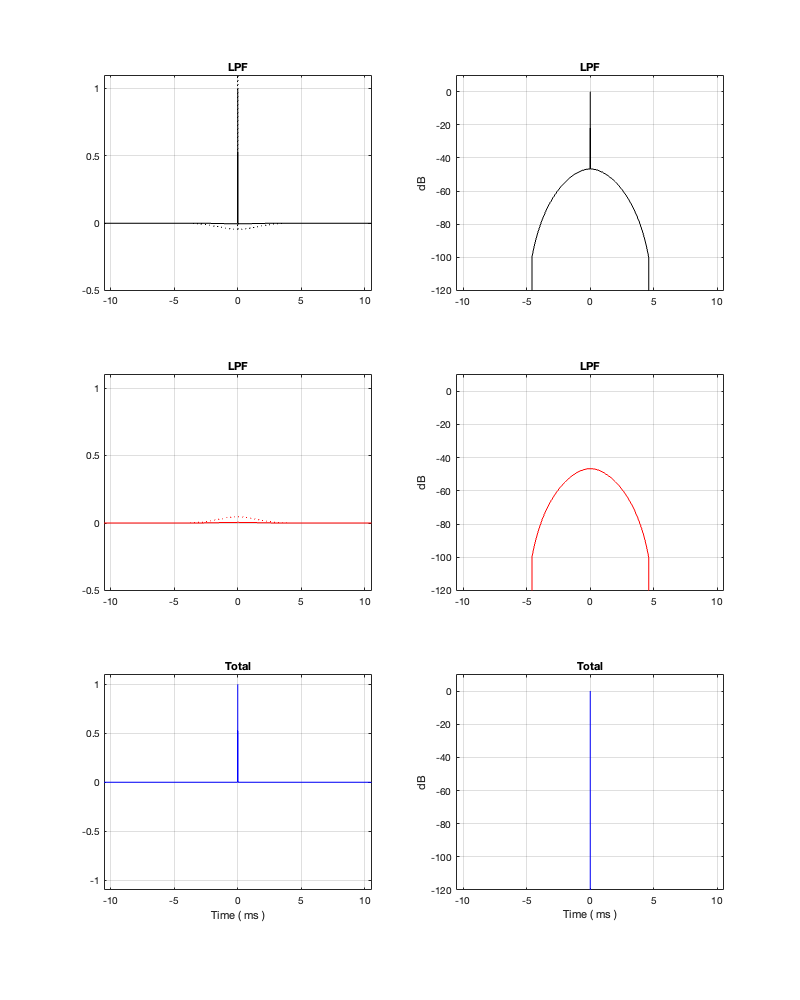

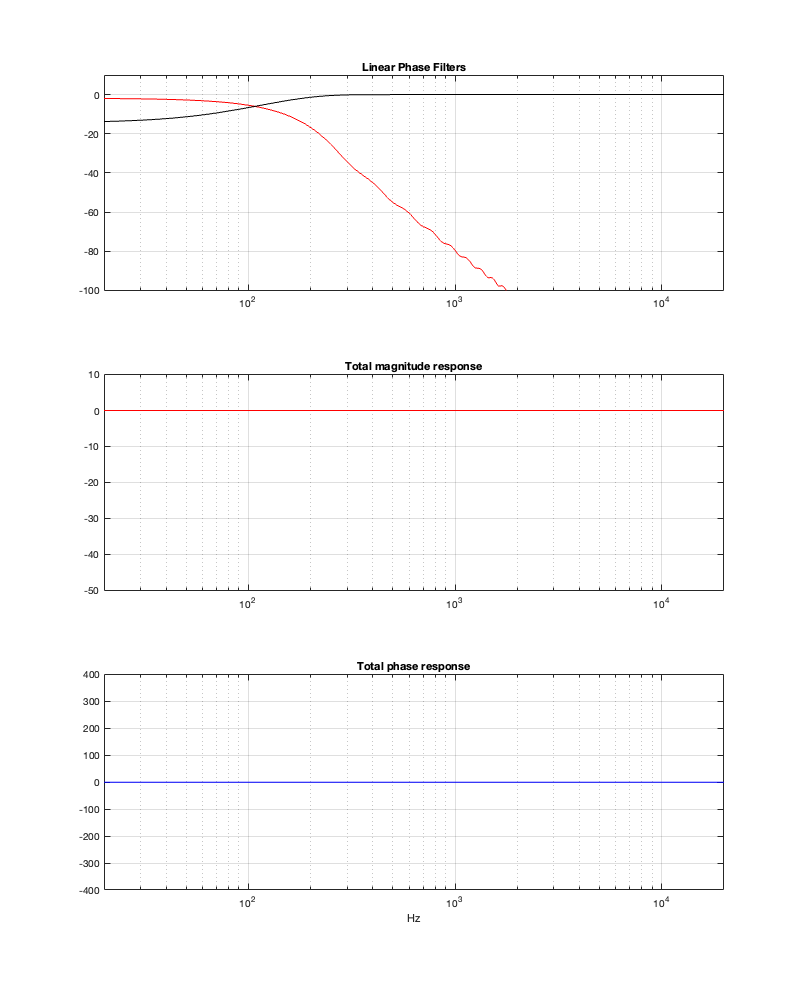

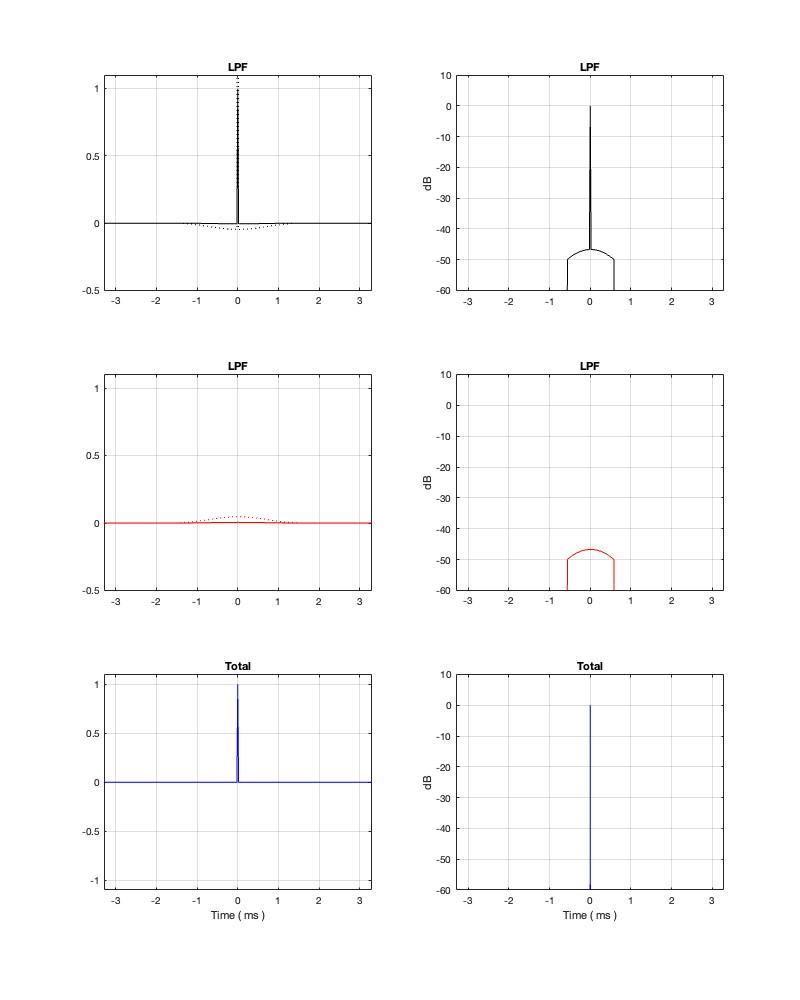

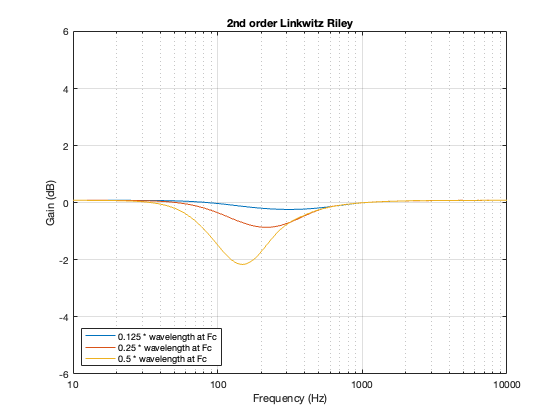

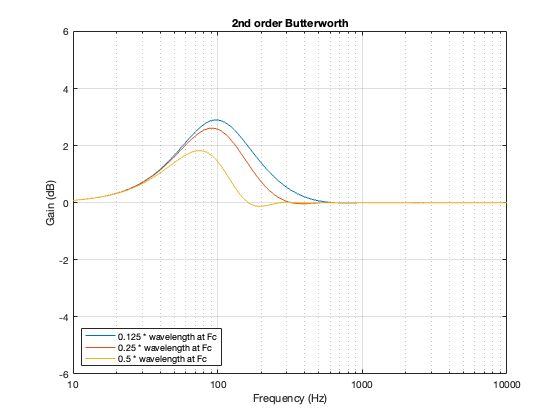

- “Constant-Voltage Crossover Network Design” by Richard Small

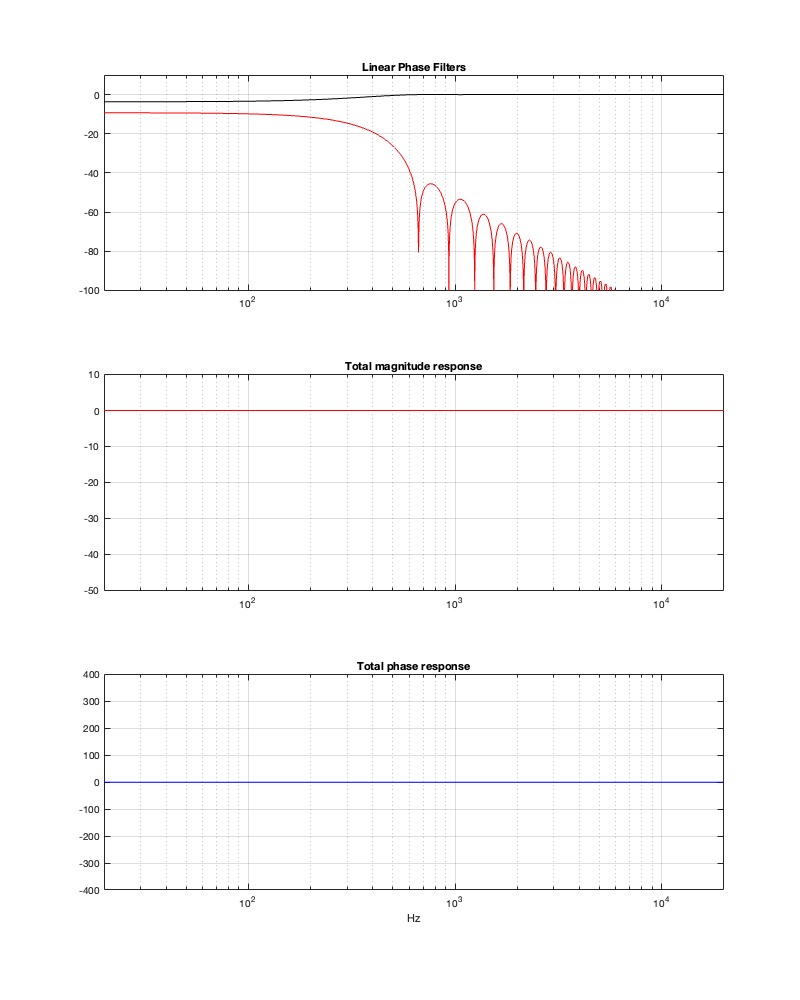

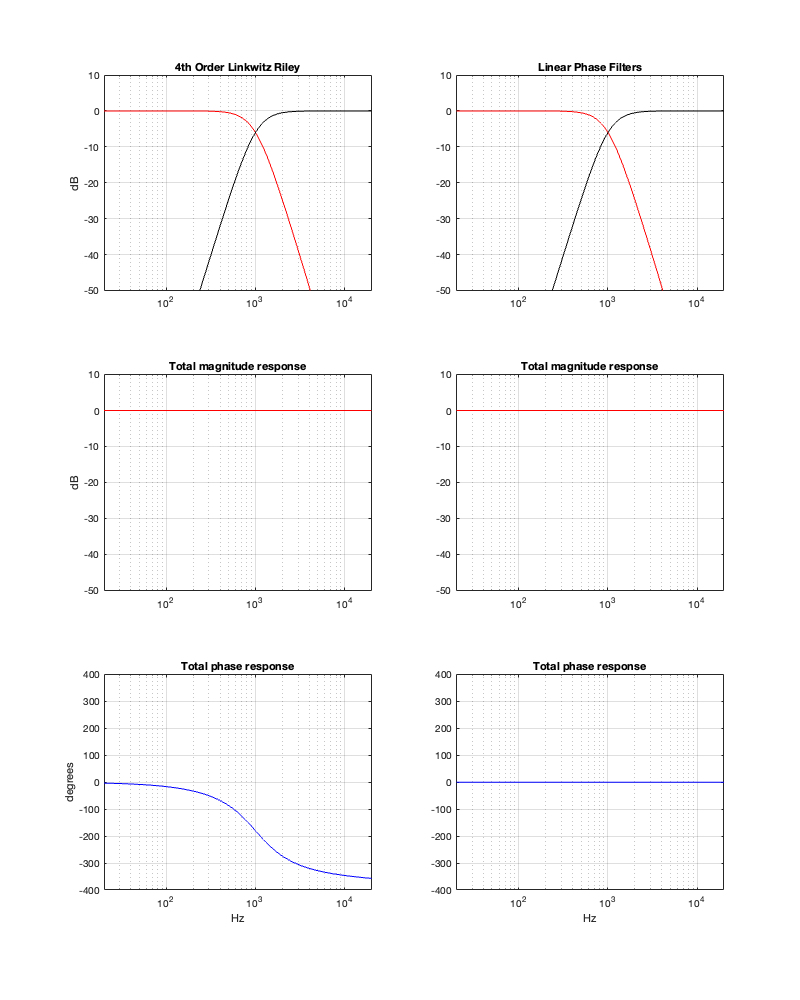

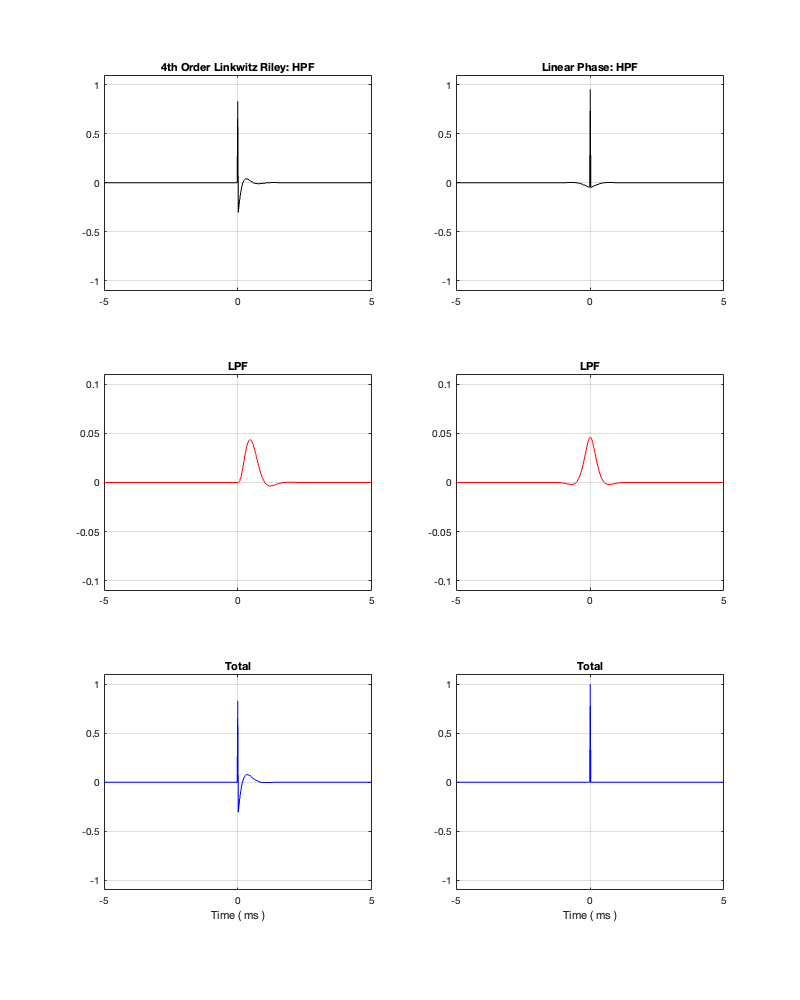

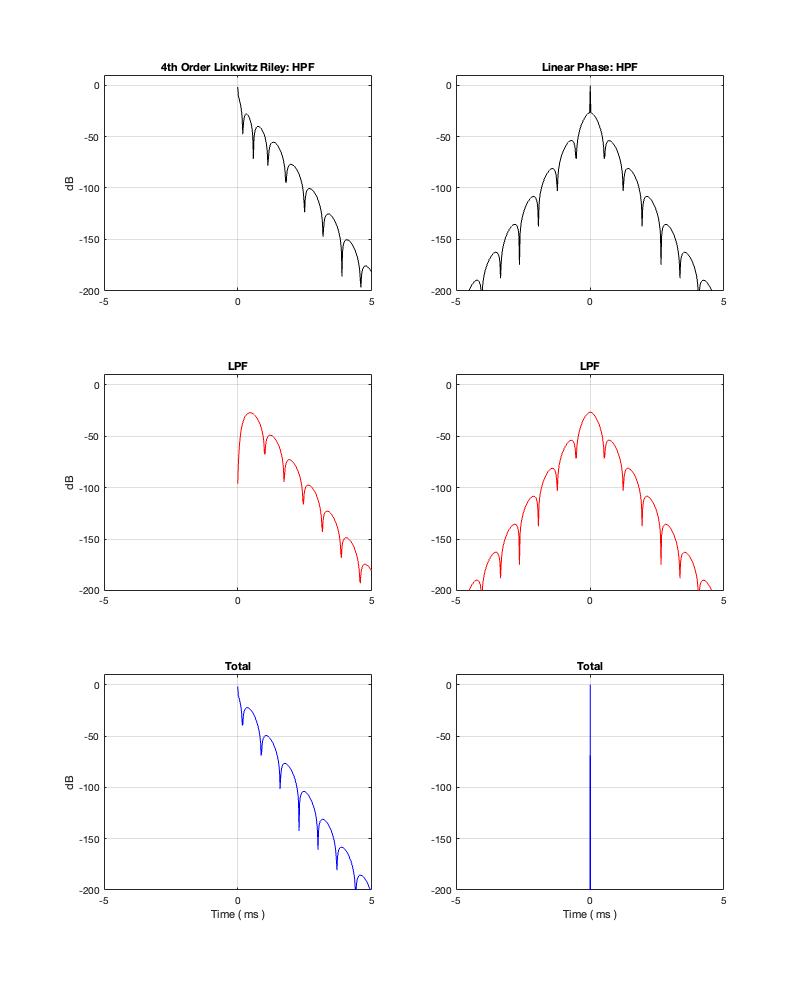

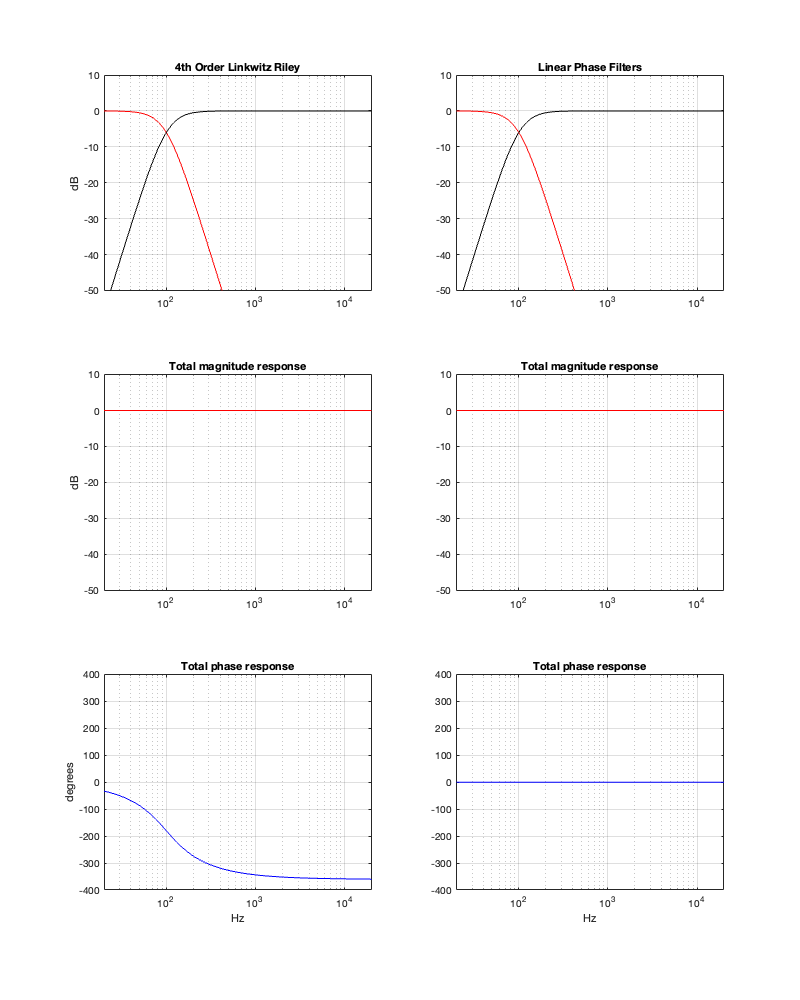

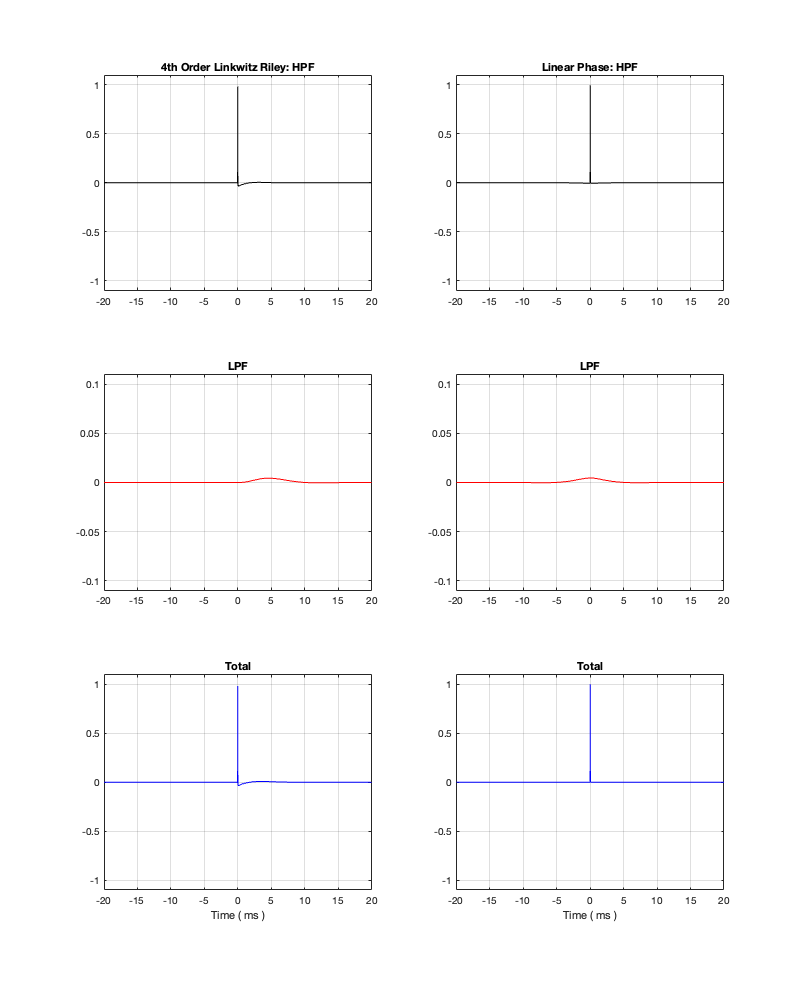

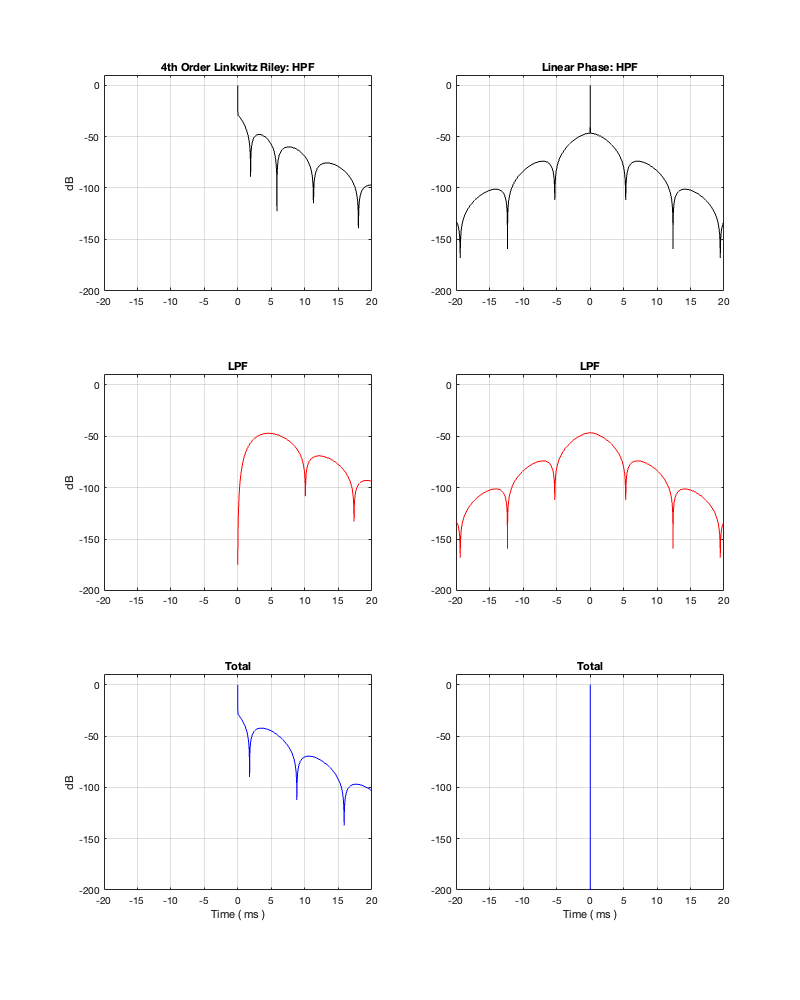

On thing that I intentionally avoided was crossover designs that use filters with extremely high orders, sometimes called “brick wall” crossovers. On paper, they avoid the possible issues with a signal in a given frequency band coming from two sources (e.g. a woofer and a tweeter), so if you ONLY consider them from this perspective, they’re a good idea. However, in my opinion, this is outweighed by the facts that you will probably get a discontinuity in the power response (unless the two drivers have identical three-dimensional radiation patterns at the crossover frequency) AND you will probably have a complete mess in the time domain. Bonkers-order filters aren’t free. (If you clicked on the link to Linkwitz’s page, above and just taken a quick glance, then you’ve probably read the statement at the top of the page that says “The sum of acoustic lowpass and highpass outputs must have allpass behavior without high Q peaks in the group delay.” One way to look at the group delay of a filter is to look at the slope of the phase response. If you make a crossover with really high-order filters, then one of the artefacts will be a high slope in the phase response around the crossover frequency.)

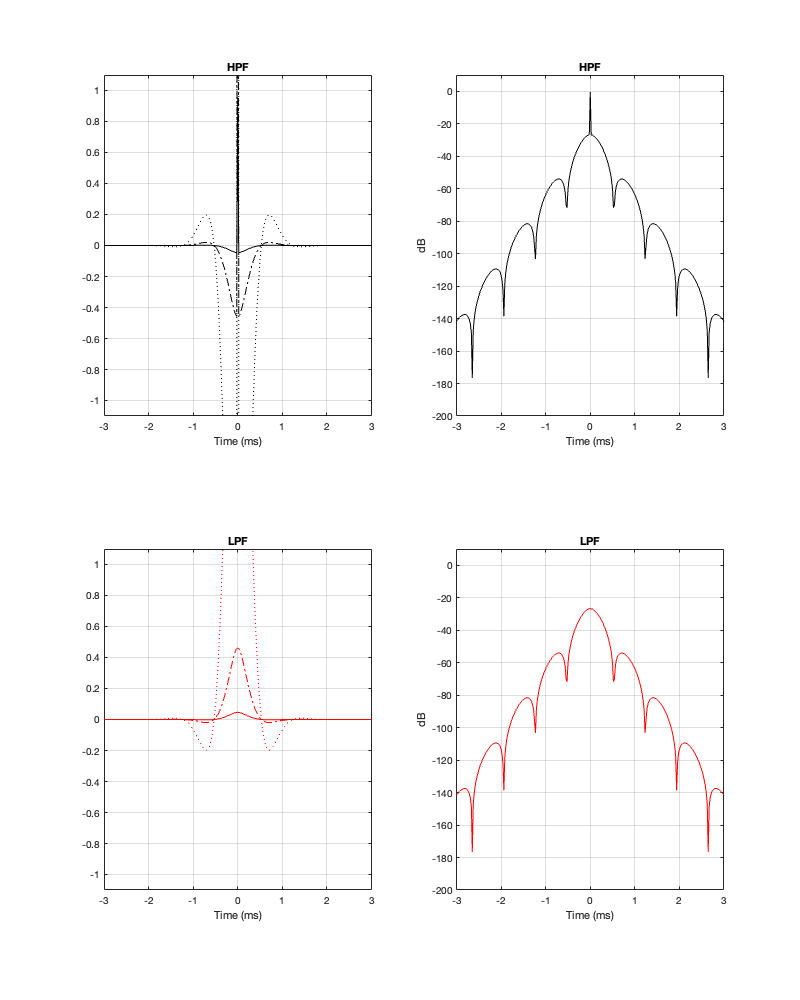

One other thing that I have not mentioned is the incorrect naming that is often associated with crossovers and filters in general. Many people say “FIR Filter” (Finite Impulse Response) when they actually mean “Linear phase filter”. It’s important to remember that you can’t have a linear phase filter without an FIR filter implementation, but certainly not all FIR filters are linear phase. (Weirdly, a linear phase filter does, in fact, have an infinite impulse response, both forwards and backwards in time… But that’s a description of the filter’s response and not how it would be implemented in a DSP-based signal flow.) This incorrect usage drives me nuts. (Then again, many things like this do. For example, I get annoyed when HR people draw a triangle on a whiteboard and call it a pyramid. You never know what’s going to set me off on a pedantic rant about nomenclature.)

The other thing that I didn’t talk about was another way to look at a Butterworth two-way crossover, in which you see it as lacking a component in the s-domain (using Laplace analysis), which is the reason its sum has an allpass characteristic. If you add the missing component (for example, using a third loudspeaker driver), then the allpass behaviour disappears. This is the concept behind Bang & OIufsen’s “Uni-phase” series of loudspeakers in the 1970s and 1980s. If you want to learn more about this, I’ve already written about it here, and Erik Bækgaard’s original paper from 1977 describing the idea more fully can be found here.

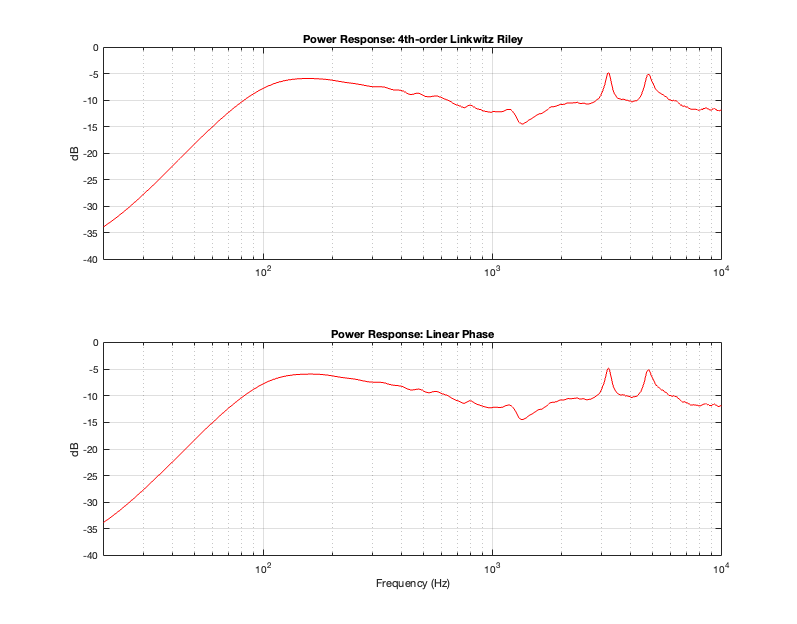

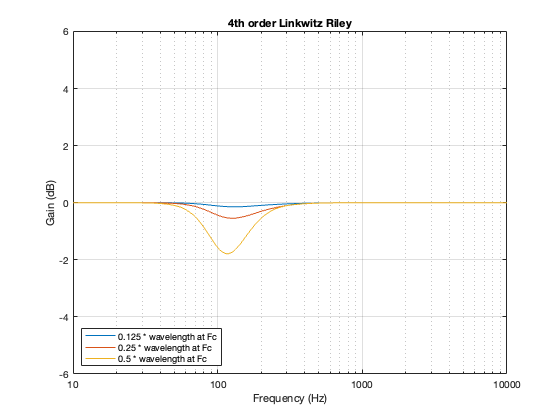

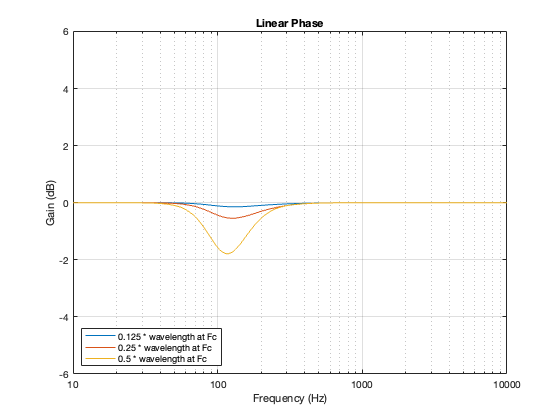

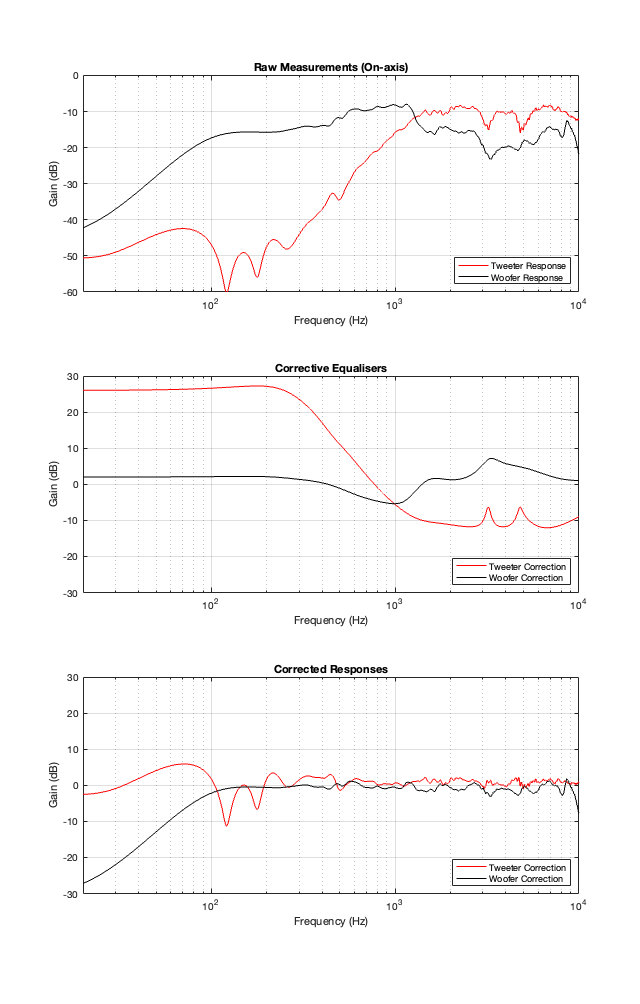

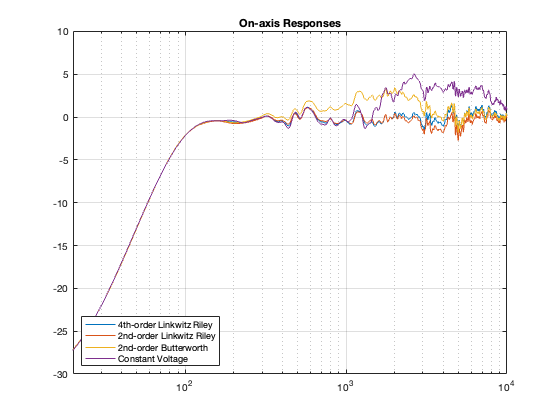

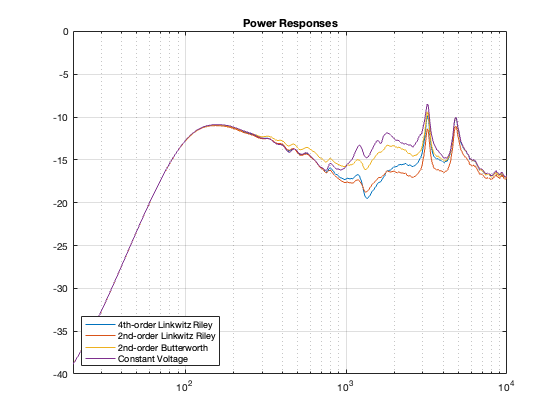

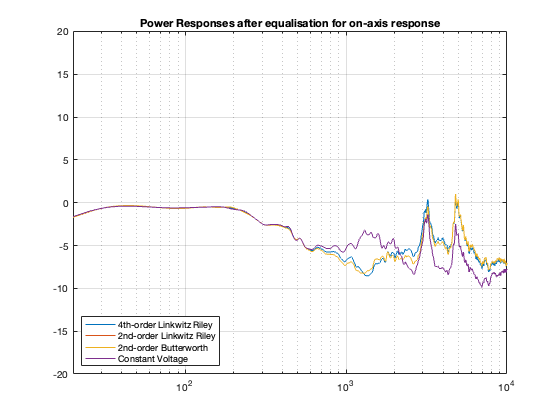

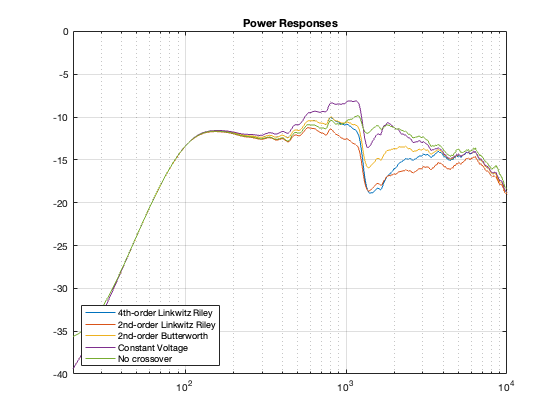

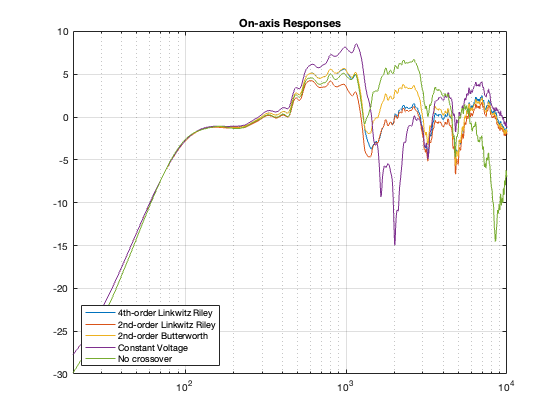

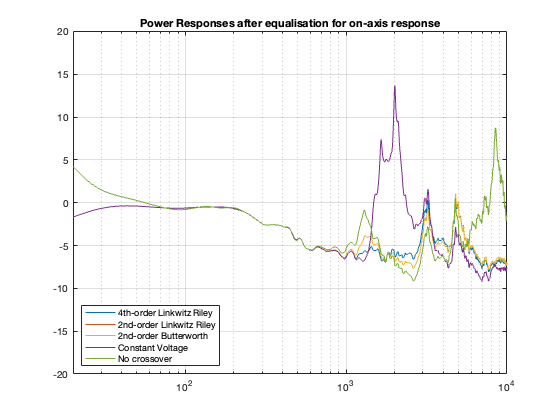

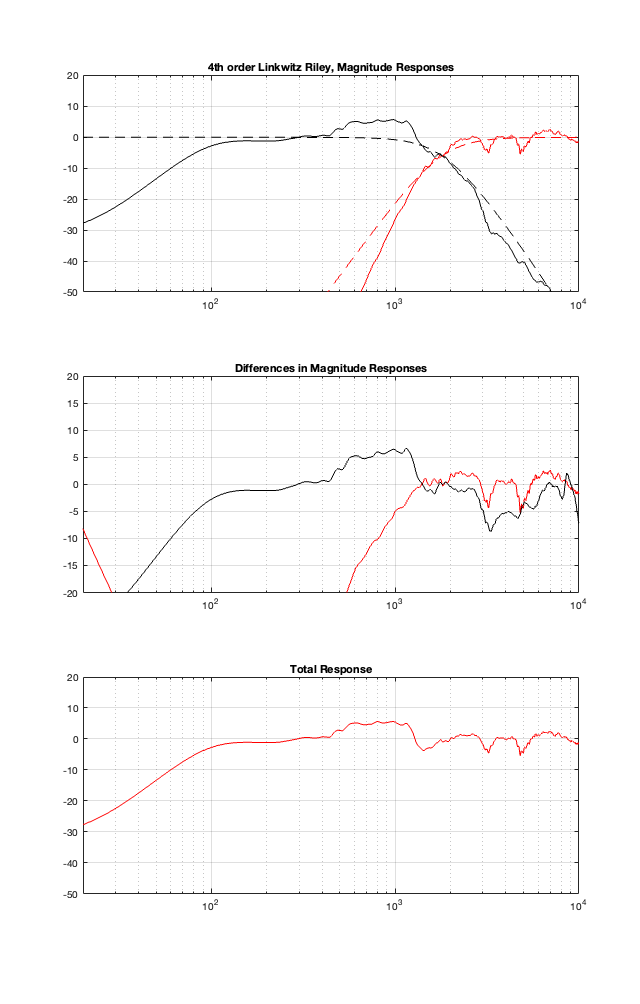

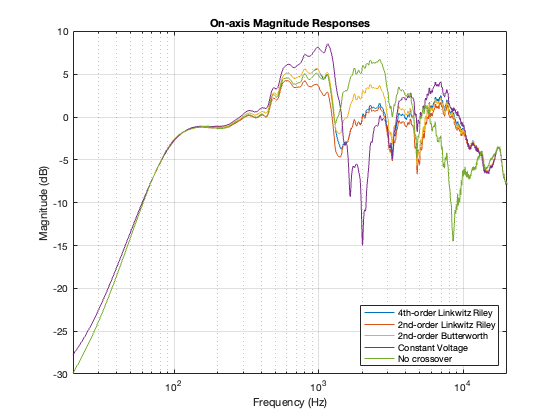

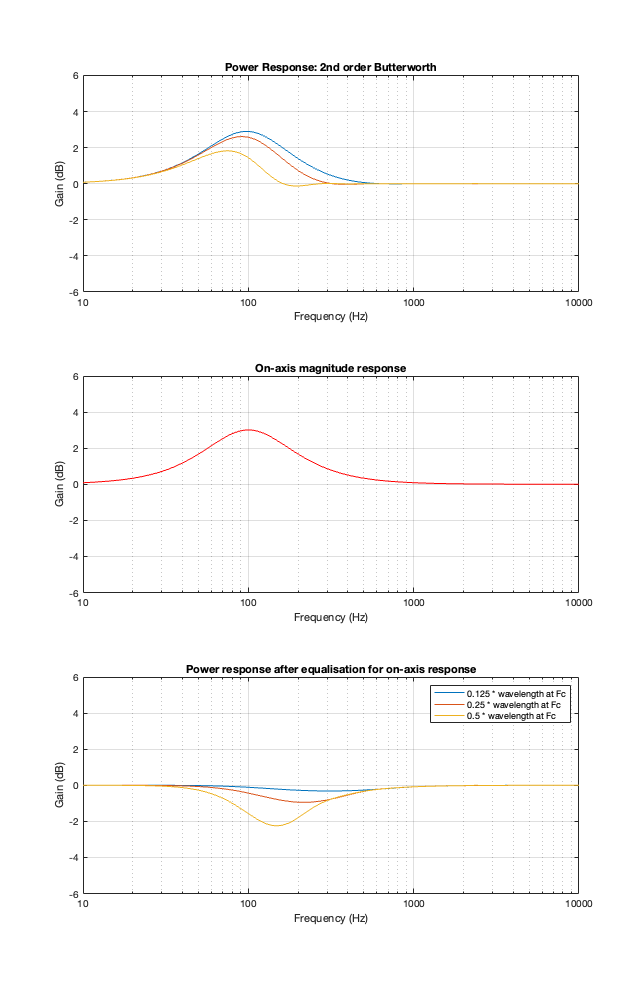

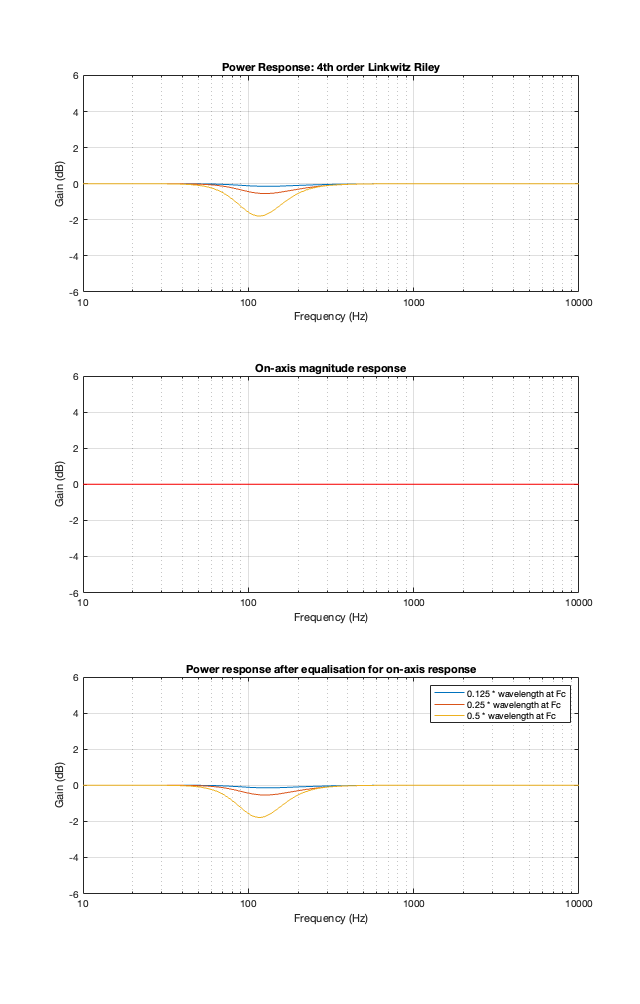

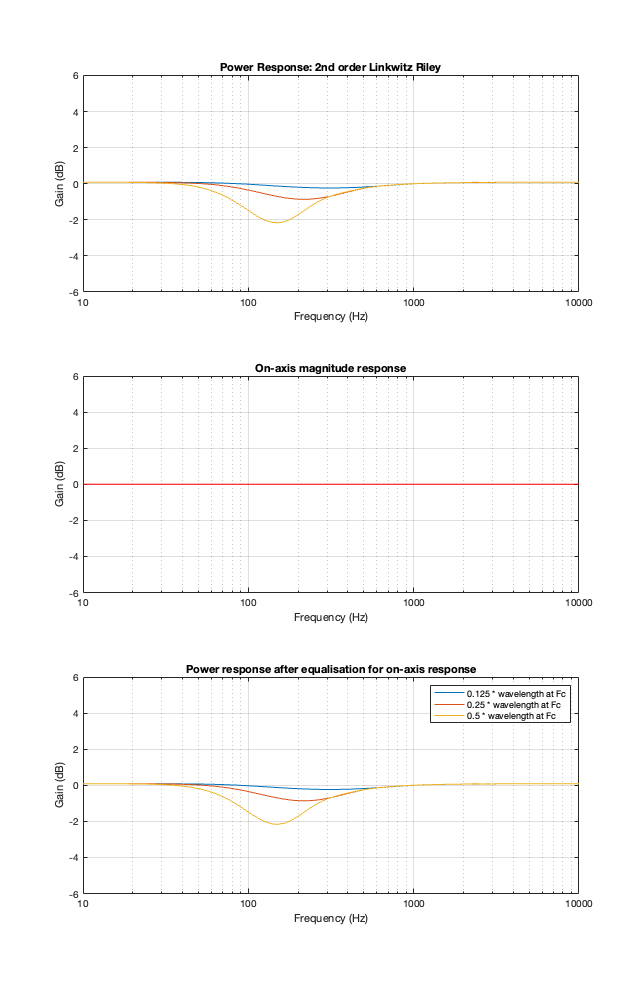

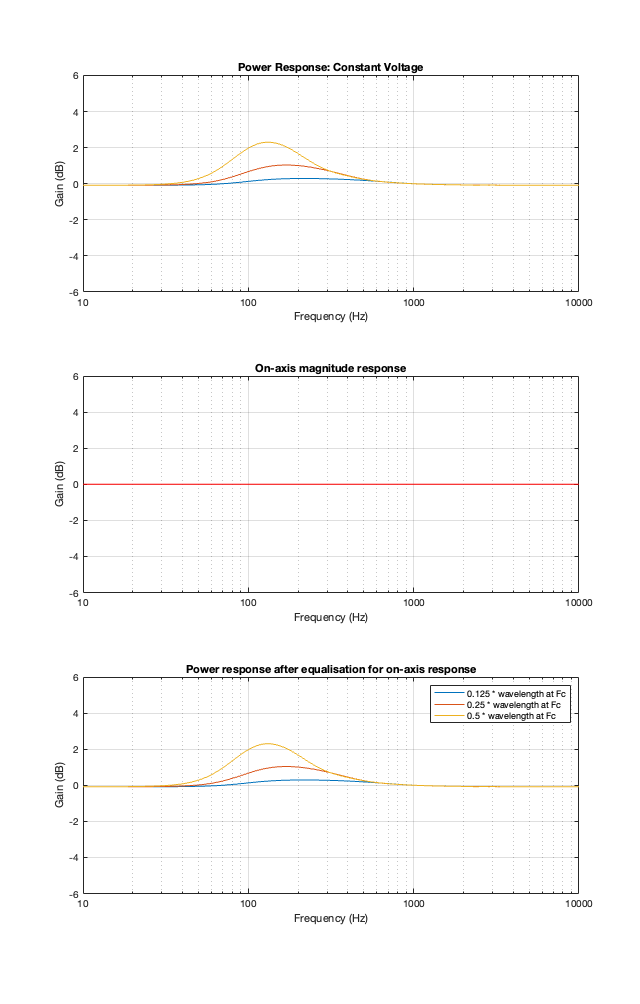

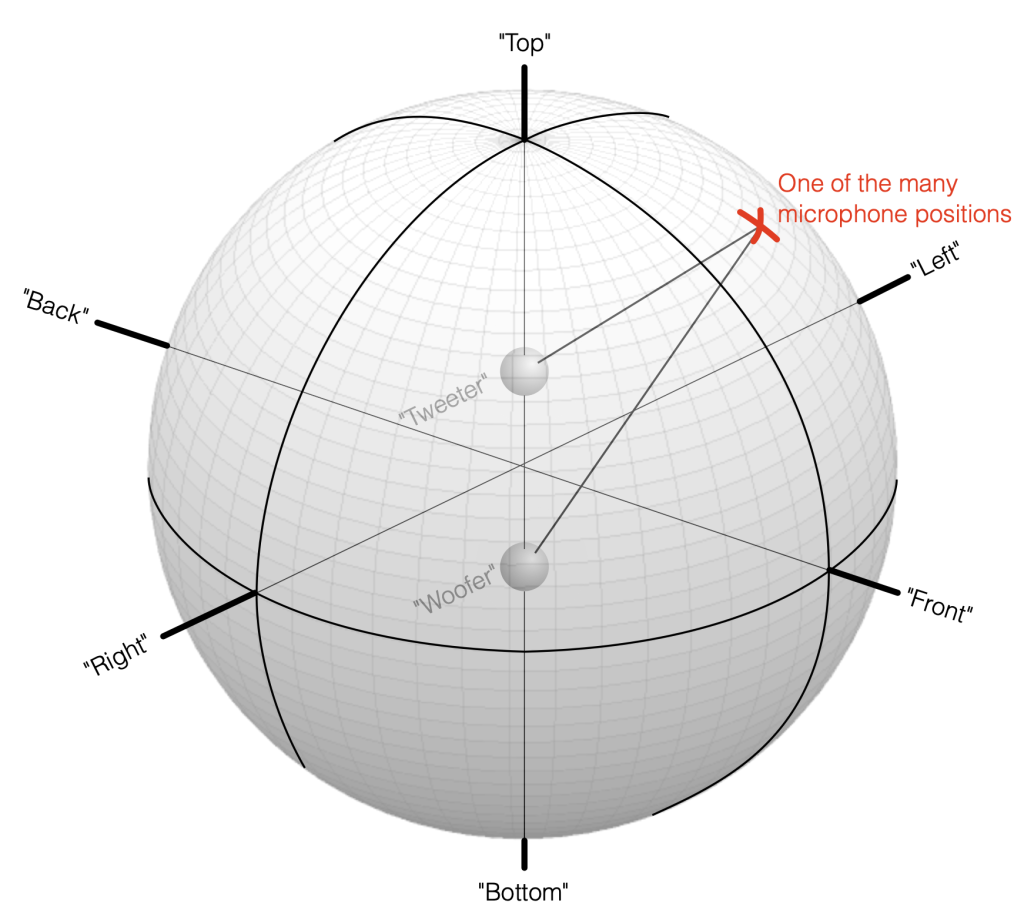

Finally, hopefully, you won’t come away from all of this with a conclusion that one crossover is the winner. A crossover is just one component in a long series- and parallel-chain of components that make up a loudspeaker. Changing any of the other components may require making a different decision about another. And, in order to make that decision, you can’t just consider the on-axis response (unless you live alone in an anechoic chamber (or outdoors…). You also need to think about things like

- the off-axis responses

- the power response

- the phase response

- the time response

and maybe also - the implications on latency

- your required signal processing power (e.g. in MIPS)

- maybe some other stuff if you have checked all those boxes.

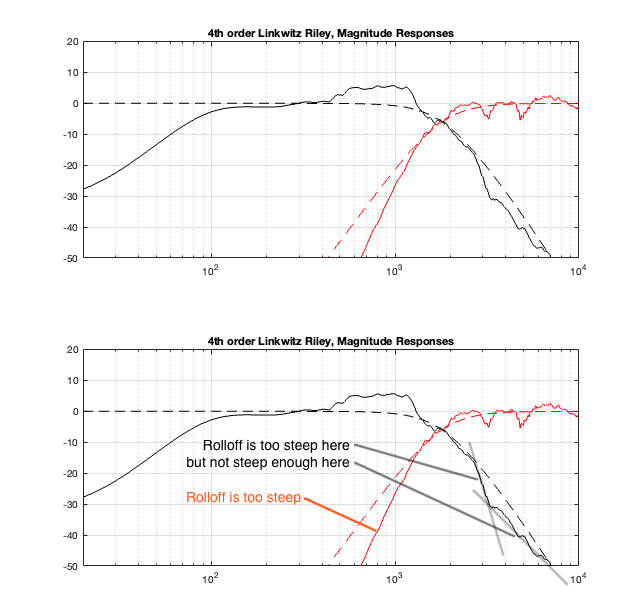

On the other hand, after all this, you should also know that you can’t just implement a crossover ignoring everything else in the chain, and think that it’ll just work. It won’t.