By now, we should know a couple of things:

- you cannot just stick a crossover in front of some loudspeaker drivers and expect the total system to behave

- the on-axis response and the power response of a loudspeaker are related to each other

- the power response is also very dependent on the directivity characteristics of the individual drivers and they way they interact (including the crossover’s effects) in three-dimensional space

- if you fix something for the on-axis response, you might do damage to the power response

Now we’re going to do something that I didn’t do in the previous posting. I’ll use the crossover responses as a TARGET for the total response of the crossover + driver outputs.

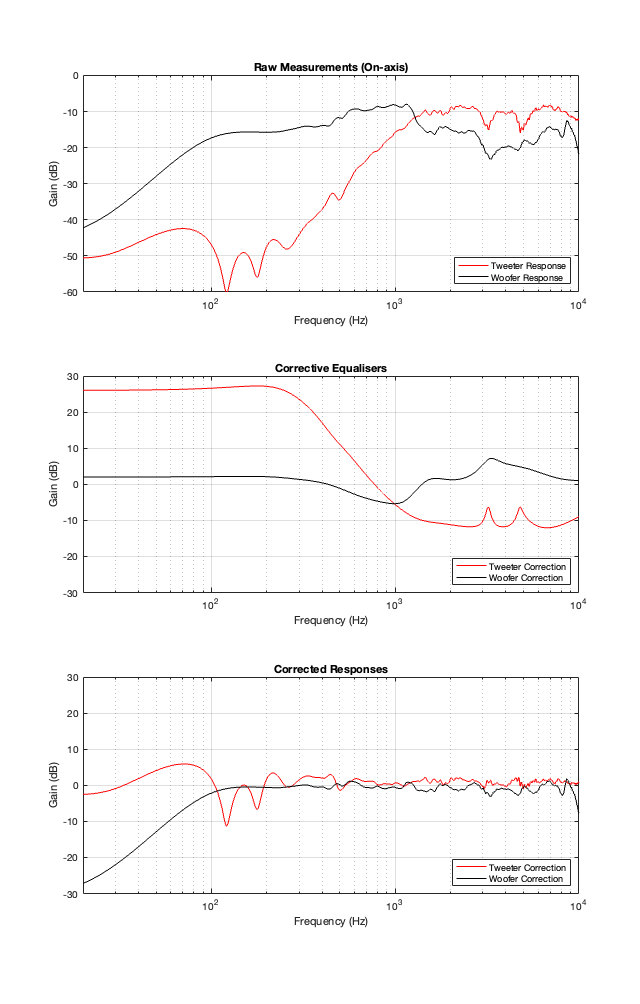

The top plot in Figure 11.1 shows the magnitude responses of the raw measurements of the tweeter and woofer that we looked at in Part 10. I then used these measurements to quickly make some agressive equalisation curves to force them to be flat-ish. These two equalisation filters are shown in the middle plot of Figure 11.1. Each of these is the product of a LOT of filters that I put in to result in the curves of the combined total responses that you see in the bottom of Figure 11.1.

In theory, if you play the tweeter and woofer through their respective equalisers, you will be able to measure the magnitude responses that you see there in the bottom of Figure 11.1. Of course, a 1″ tweeter can play a 20 Hz sine tone, it just can’t do it very loudly. So, this is NOT the solution to making a loudspeaker. This is just for illustrative purposes.

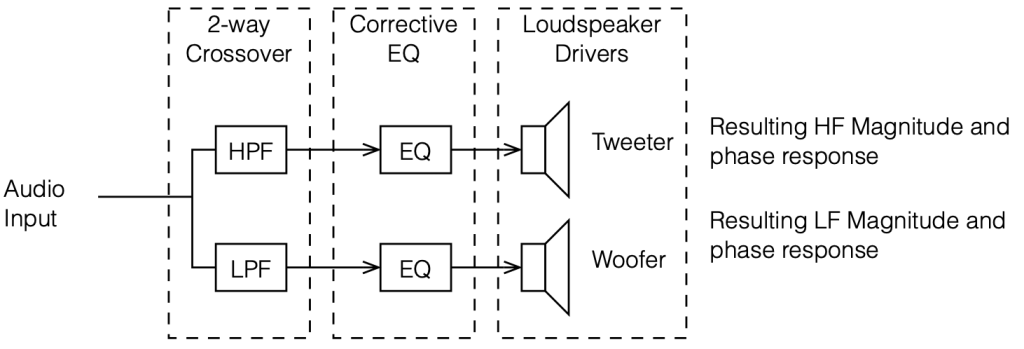

If I then apply our crossovers to these equalised loudspeaker drivers as shown in the signal flow above, I get the plots below.

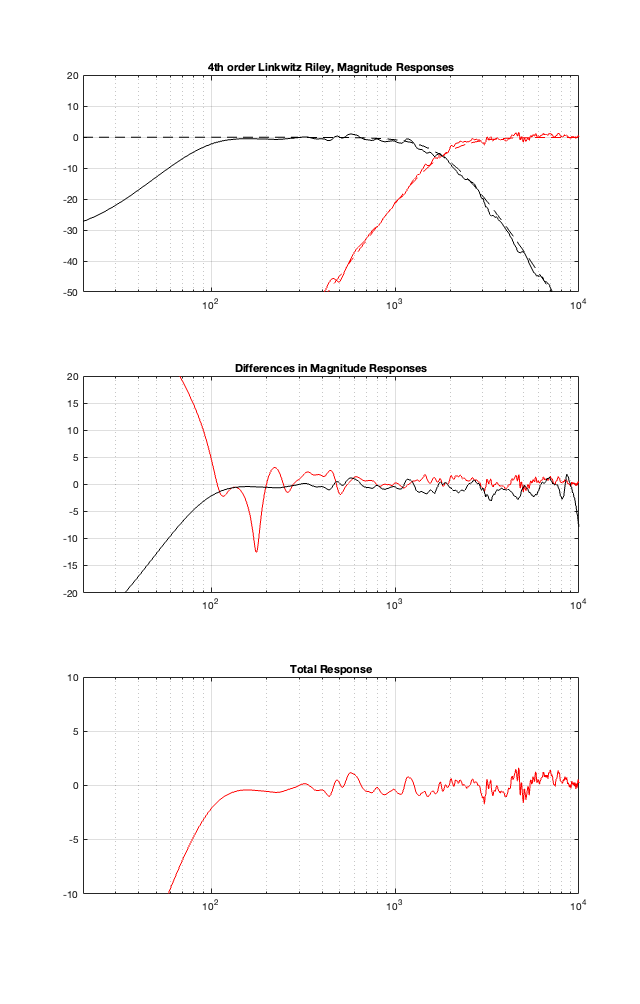

4th order Linkwitz Riley

The top plot of Figure 11.3 shows the target magnitude responses of a 4th-order Linkwitz Riley crossover as the dotted lines. The solid lines show the measured outputs of the woofer and tweeter, including the corrective equalisation.

The middle plot shows the differences in what I want the crossover to do, and what the actual responses are at the outputs of the loudspeaker drivers. Again, in a perfect world, these would be two flat lines, sitting on 0 dB at all frequencies.

The bottom plot is the resulting on-axis response of the loudspeaker, combining the two outputs. Notice how much flatter it is than the one we had in Part 10. (the scale of this plot is much tighter than it was in the previous posting…)

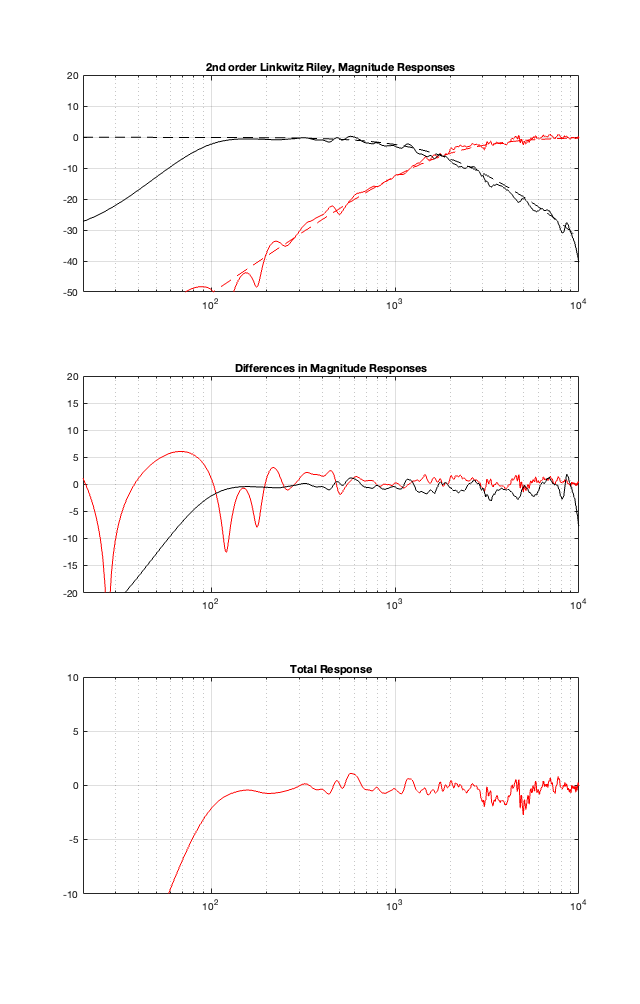

2nd Order Linkwitz Riley

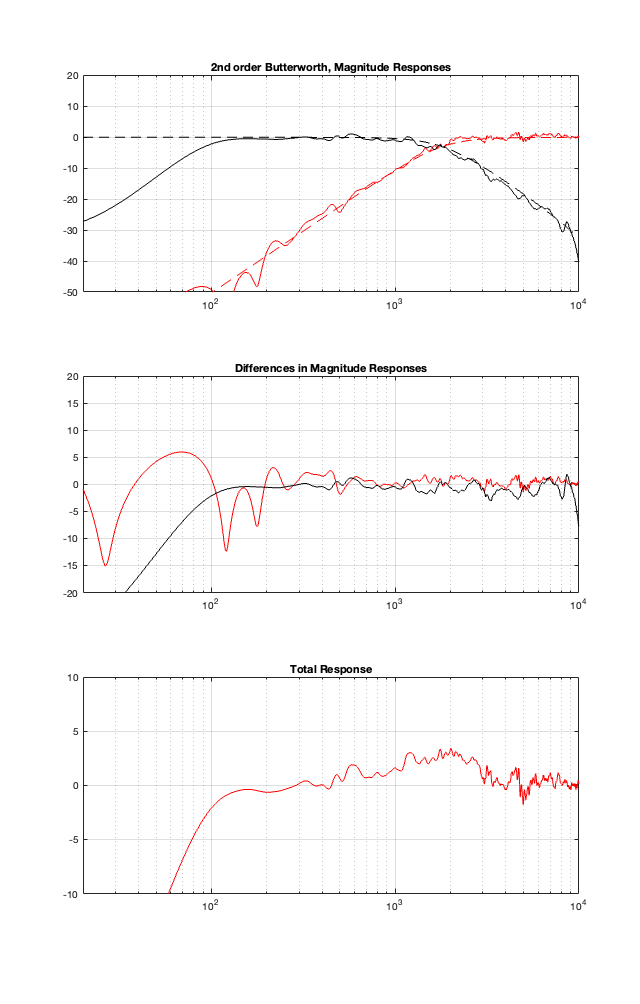

2nd order Butterworth

One comment here. Notice the +3 dB bump around the 1.8 kHz crossover, just like we would expect from a 2nd-order Butterworth crossover.

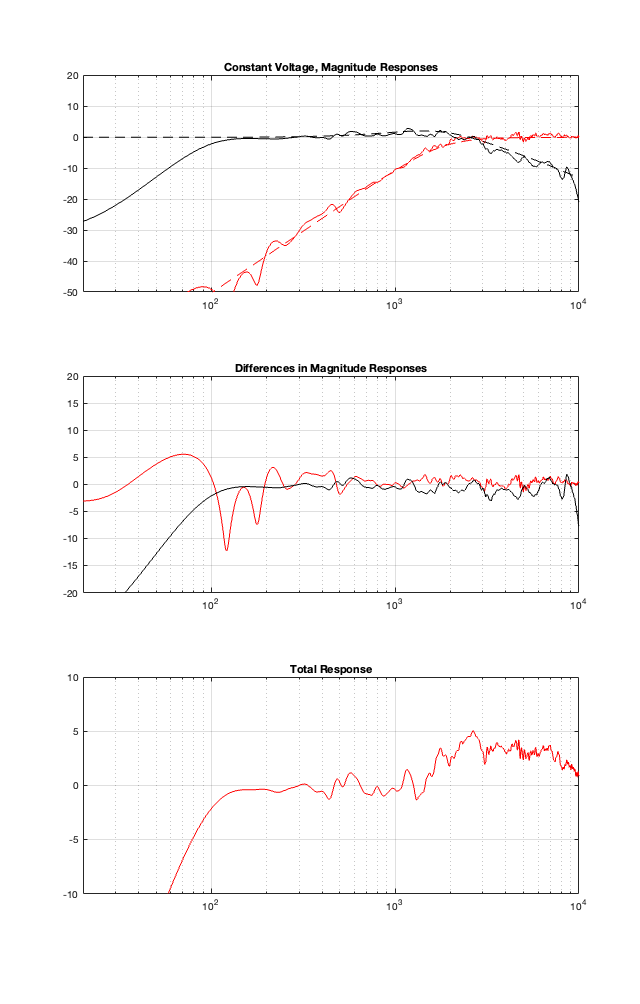

Constant Voltage

This one is interesting, but not surprising. You can see here that there is an unexpected high-shelving characteristic here in the total response. The reason for this is the combination of a number of things:

- the corrective EQ that I made was a bit quick-and-dirty, only using minimum phase filters

- a constant voltage crossover is very sensitive to phase variations in the two signal paths. If they don’t behave as one would expect (and they don’t in this loudspeaker because of my corrective EQ) then things get a little weird.

- Finally, take a look at the dotted lines. You can see there that the woofer has a lot of contribution in the high end. This combines with the previous point to make the total a little unpredictable.

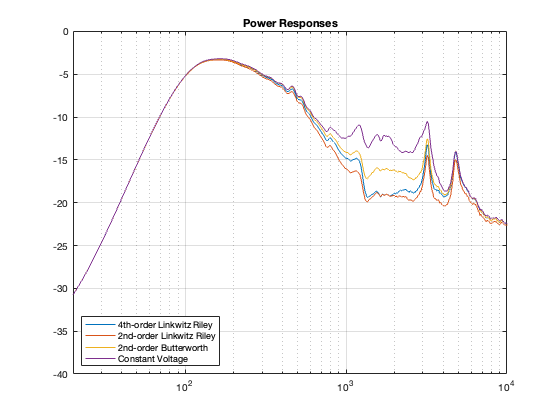

Power Responses

Finally, you might ask what the power responses look like for these loudspeakers. They’re shown below in Figure 11.7

You might be surprised by the fact that, although most of our on-axis magnitude responses look pretty flat, the Power Responses are not nice, straight lines with a general downward slope. In fact, they have some pretty ugly peaks there. Why? This is because I did my equalisation based on only one on-axis measurement. So, by focusing all of my attention on that one point in space, I sacrificed the response of the spherical radiation. If we were making a loudspeaker for an anechoic chamber, and we had only one chair and no friends, this would be fine. However, this would NOT be a good solution for a loudspeaker that’s designed for a real room that has some reflections.

On the other hand, there is one interesting thing that’s worth noting in those plots. Look at the flat, horizontal portion of some of the curves between about 1.2 kHz and 3 kHz. Those are straight lines in that frequency band because I forced them to be that way with my EQ. However, they’re flat, horizontal lines because the loudspeaker is more omnidirectional in that region, probably related to the fact that the tweeter is taking over here. This is another way of seeing the information shown in Figure 6 in this posting about loudspeaker directivity.