So, you want to build a loudspeaker…

One of the first things you’ll find out is that, if you’re building a loudspeaker with moving coil drivers, and unless you want a loudspeaker with very limited capabilities, you’ll probably need to use more than one driver. Starting small, you’ll at least need a bigger driver to produce the lower frequencies and a smaller driver to produce the higher ones. No surprise so far – many people lead meaningful lives with just a tweeter and a woofer.

However, you’ll probably need to ensure that the tweeter doesn’t get too much signal at low frequencies, and the woofer doesn’t get too many highs. In order to do this, you’ll need a crossover. Still no surprises. Most people who build a loudspeaker already know that they’ll need a crossover to keep their drivers happier.

Now for some new stuff – at least for some people. When you make a crossover, you must remember to keep the driver’s characteristics in mind. You can’t just slap a high pass filter on the tweeter and a low pass filter on the woofer and expect things to work. The tweeter is already behaving as a high pass filter all by itself. If the characteristics of the tweeter’s inherent high pass are what you want, then you don’t want to duplicate that filter in the electronics. So, design your filters wisely. I will probably come back to some examples of this some time in a future posting.

However, that is not the topic for today. For today, we will assume that we are building a loudspeaker using two very special drivers. They are:

- infinitely small

- have bandwidths that go from DC to infinity

- have “perfect” impulse responses

- and therefore have completely flat phase responses

In other words, we will pretend that each of our drivers is a perfect point source. We’ll also assume that they are not mounted on a baffle (a fancy way of saying “on the front of a box” – usually…). Instead, they’re just floating in space, arbitrarily 25 cm apart (one directly above the other). We’ll arbitrarily make the crossover frequency 500 Hz. Finally, let’s say that we’re arbitrarily 2 m away from the loudspeaker.

The reason for all of these assumptions is that, for the purposes of this posting, we’re only interested in the effects of the crossover on the signal, so I’m making everything else in the system either perfect or non-existent. Of course, this has nothing to do with the real world, but I don’t really care today.

So, if you’ve done a little research, you’ll know that there are a plethora of options to chose from when it comes to crossovers. I’ll assume that we’re building an active loudspeaker with a DSP so we can do whatever we want.

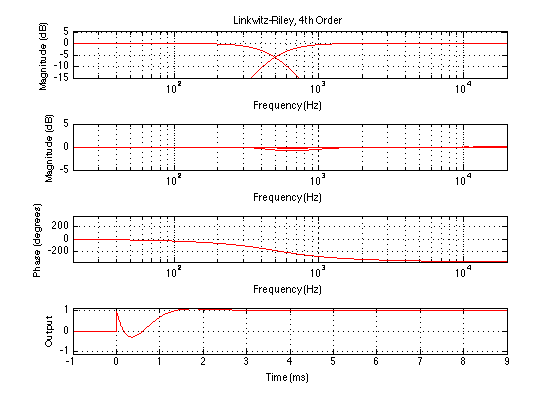

Linkwitz Riley, 4th Order

Let’s start with Old Faithful: a 4th-order Linkwitz-Riley crossover. This is implemented by putting two 12 dB/oct Butterworth filters in series, each with a cutoff frequency equal to the intended crossover frequency. (If you’re using biquads, set your Q to 1/sqrt(2) on each filter). The total low pass section will have a gain of -6.02 dB at the crossover frequency (so will the total high pass section). Since the two sections are 360° out of phase with each other at all frequencies, they’ll add up to give you a total of 0 dB when they sum together at any frequency. However, you must remember that the filter sections used in the crossover have an effect on the phase response of the re-combined signal. As a result, when the two are added back together (at the listening position) the total will also have a modified phase response – even when you are on-axis to the loudspeakers, (and equidistant to the two loudspeaker drivers).

It is also important to remember that the phase relationship of the two sections (coming from the tweeter and the woofer) is only correct when those two drivers are the same distance from the listener. If the tweeter is a little closer to you (say, because the tweeter is on top and you stood up) then its signal will arrive too early relative to the woofer’s and the phase relationship of the two signals will be screwed up, resulting in an incorrect summing of the two signals.

How much the total is screwed up depends on a bunch of factors including

- the relative phase responses of the filters in the crossover

- the phase responses of the drivers (we’re assuming for this posting that this is not an issue, remember?)

- the deviation in those phase responses caused by the mis-alignment of distances to the drivers

The result of this is a deviation in the vertical off-axis response of the loudspeaker. How bad is this? Let’s look!

This figure shows 4 plots. The top one shows the magnitude responses of the two individual sections. As you can see, the crossover frequency is 1 kHz, and both sections are 6 dB down at that frequency.

The second plot shows the total magnitude responses at 5 different vertical angles of incidence to the loudspeaker: -30°, -15°, 0°, 15°, and 30°. So, we’re going from below the loudspeaker to above the loudspeaker. It’s not obvious which plot is for which angle because, for the purposes of this discussion, it doesn’t matter. I’m only interested in talking about how different the loudspeaker sounds at different angles – not the specifics of how it sounds different.

The third plot shows the total phase response of the system, at a position that is on axis to the loudspeaker (and therefore equidistant to both drivers). As you can see there, a perfect 2-way loudspeaker with a 4th order Linkwitz-Riley crossover behaves as a 4th-order allpass filter. In other words, at low frequencies, the output is in phase with the input. At the crossover frequency, the output is 180° out of phase with the input. At high frequencies, the output is 360° out of phase with the input.

The fourth plot shows the step response of the total system, at a position that is on axis to the loudspeaker (and therefore equidistant to both drivers). As you can see there, a perfect 2-way loudspeaker with a 4th order Linkwitz-Riley crossover does not give you a “perfect” step response – it can’t, since it acts an allpass filter. The weird shape you see there is cause by the fact that the high frequencies are not “in phase” with the low frequencies. (I know, I know… different frequencies cannot be “in phase”.) Since different frequencies are delayed differently by the total system, they do not add up correctly in the time domain. Thus, although the total output in terms of magnitude is flat (hence the flat on-axis frrequency response) the time response will be weird.

Looking in detail at the step response plot, you can see that it takes about 1.5 ms for the total output to settle to a value of 1. The actual time that it takes is dependent on the crossover frequency. The lower the frequency, the longer it will take. It’s the shape of the step response that’s determined by the crossover’s phase response. What can be seen from the shape is that the high-frequency spike hits first (as we would expect), then the step response drops back to a negative value before heading upwards. It overshoots, peaking at a value of 1.0558 before coming back down, undershooting slightly (to a value of 0.9976) and finally settling at a value of 1. Note that these values won’t change with changes in crossover frequency – they’ll just happen at a different time. The higher the frequency, the faster the response.

Whether or not this modified time response is worth worrying about (i.e. can you hear it) is also outside of the scope of today’s discussion. All we’re going to say for today is that this temporal distortion exists, and it is different for different crossover strategies as we’ll see below.

Linkwitz-Riley 2nd Order

A second possible crossover strategy is to use a 2nd-order Linkwitz Riley. This is similar to a 4th-order, except that instead of putting two 12 dB/octave Butterworth filters in series to make each section, you put two 6 dB/octave Butterworth filters in series.

Since the total filters applied to make the high pass and low pass sections of this crossover are each made with only two first-order filters (instead of two second-order filters), the high pass and low pass sections are only 180 degrees out of phase with each other (at all frequencies). Consequently, in order to get them to add back together without cancelling completely at the crossover frequency, you have to invert the polarity of one of the sections. (We’ll do this to the high pass section, just in case you can hear your woofers pulling when they ought to push when a kick drum hits). On the plus side, since they’re 180 degrees out of phase at all frequencies, if you DO flip the polarity of your high pass section, they’ll add back together (on axis) to give you a flat magnitude response.

As you can see in the above plots, the slopes of the high pass and low pass sections in this crossover type are more gentle than in the 4th order Linkwitz Riley. This should be obvious, since they have a lower order. In the second plot, you can see that, on-axis, the magnitude response is flat, just as we would expect. However, there are implications on the off-axis response. The deviation from “flat” is greater with the 2nd-order LR than it is with the 4th-order version. Not by much, admittedly, but it is greater. So, if you’re concerned about deviations in your off-axis response in the vertical plane, you might prefer the 4th-order LR over the 2nd-order variant.

If, however, you lay awake at night worring about phase response (you know who you are – yes – I’m talking you YOU) then you might prefer the 2nd-order Linkwitz Riley, since, as you can see in the third plot, the total output is only 180° out of phase with its input in the worst case – only half that of the 4th-order variant. On the other hand, since it’s 180° out of phase, that means that a high voltage going into the system (at high frequencies) will come out as a low pressure. So, if you’re the kind of person who lays awake at night worrying about “absolute phase” (you know who you are – yes – I’m talking to YOU) then this might not be your first choice.

Finally, take a look at the step response in the final plot. You’ll notice immediately that the high frequencies are 180° out iof phase, since the initial transient of the step goes down instead of up. You’ll also notice that the step “recovers” to a value of 1 a little faster than the 4th order Linkwitz Riley. Note that, a 2nd order LR, doesn’t have the overshoot that we saw in the 4th order version.

Butterworth, 12 db/octave

Possibly the most common passive crossover type (and therefore, possibly the most common crossover type, period!) is the 12 dB/octave Butterworth crossover. This is made by using a 2nd-order Butterworth filter for each section (the high pass and the low pass).

You’ll notice in the top plot that this means that the filter sections are only 3 dB down at the crossover frequency. This has some implications on the on-axis response. Since the two filter sections are 180° out of phase with each other (at all frequencies – just like the 2nd-order LR crossover) then we have to flip the polarity of one of the sections (the high-pass section again, for all the same reasons) to prevent them from cancelling each other at the crossover frequency when they’re added back together. However, now we have a problem. Since the two sections are in-phase (due to the 180° phase shift plus the polarity flip) and since they’re only 3 dB down at the crossover frequency, when they get added back together, you get more out than you put into the system. This can be seen in the second plot, where the total magnitude response has a bump at the crossover frequency – even when on-axis.

Of course, a 3 dB bump in the magnitude response will be audible, at the very least as a change in timbre (3 dB is, after all, twice the power). We can also see that there is a small, but visible change in the overall magnitude response as you change the vertical angle to the listener.

The third plot shows that a 12 dB/Octave Butterworth crossover, when all other issues are ignored, acts as a 2nd-order allpass filter with a worst-case phase distortion of 180°.

Finally, the fourth plot shows that its step response is similar, but not identical to, the 2nd-order LR crossover. The initial transient goes negative because we have inverted the polarity of the high pass section. Unlike the 2nd-order LR (but similar to the 4th-order LR), however, there is an overshoot and undershoot before the response settles at a value of 1. That overshoot reaches a maximum of 1.1340, and the subsequent undershoot goes down to 0.9942.

Butterworth, 18 db/oct

Constant Voltage, (using a Butterworth, 18 db/oct high pass)

paul says:

HI,

very much a armature beginner. you didn’t discuss 1th order butterworth (are there other 6db types?). Will you cover this later?

Also i read that Magico uses elliptical(?) type crossovers. i’m reading up on them but …this is beyond me..

paul

your thoughts

geoff says:

Hi Paul,

I had not planned on doing 1st order crossovers, since there is so much out-of-band energy sent to the drivers that it makes them not very interesting. However, to be fair, I suppose that it wouldn’t hurt to do the graphs to show their effect on the off-axis and power responses.

As for elliptic filters, I really don’t know much about them either – however, I can see that there are some issues with respect to using them in audio processing. The first is the ripple in the passband. This will have an impact on the on-axis frequency response of a loudspeaker (link). The second issue is that an elliptic filter has a rather steep transition band – so if your drivers have different directivities around the crossover frequency, you’ll get a strange shift in the loudspeaker’s directivity in that band. The third issue is that elliptic filters have nasty responses in the time domain that might make them problematic (link). However, as Douglas Self discusses in his book “The Design of Active Crossovers (link), one way to implement an elliptic filter is to use a Butterworth filter with a notch filter, and as he says: “Elliptical filters can sometimes be very useful for crossover use, for if we have an otherwise good drive unit with some nasty behaviour just outside its intended frequency range, the notch can be dropped right on top of it.”

I know that this doesn’t help much – but I’ll come back with some info on the first-order question.

Cheers

– geoff

Michael says:

Hi Geoff,

if I get it right, the off axis response result from the defined driver distance?

If so, would a true working coaxial driver be the solution?

Kind regards

Michael

geoff says:

Hi Michael,

Unfortunately, no. Whether two or more drivers are coaxial does not imply a constant directivity.

Cheers

-geoff

Ric Lewis says:

Assuming you’re able to implement the crossover using a linear phase mechanism (FIR filter), with high-computing power, and no concern for timing delay, is there any other downside to using significantly steeper crossover slopes?

I’m using my PC to drive an active XO. I’ve read that brickwall crossovers have difficulties in reality, so I’m looking at 192db slope LR filter to minimize the overlap between the drivers.

geoff says:

Hi,

There is a POSSIBLE problem with high-order filters (assuming that the issues you point out are taken care of). This is the possibility of a discontinuity in the directivity of the loudspeaker. Let’s take an (crazily) extreme example where you cross over from a 10″ woofer to a 1″ tweeter at 3 kHz or so. At 2999 Hz, the woofer is beaming, at 3001 Hz, the tweeter is more-or-less omnidirectional. The result is that the apparent distance to sources will pull apart as I describe in this posting – a search for “constant directivity” or “controlled directivity” will lead you to other people writing about the same issue. The goal for many loudspeaker manufacturers (and one that I very firmly support) is a “constant directivity” which means that you have a directivity that is the same at all frequencies (in theory…).

Hope this helps.

Of course, if the directivity of your two drivers match closely enough at the crossover frequency, then this is not a serious issue.

Cheers

-geoff

George S. Louis says:

Dear Geof,

I noticed at least one possible mistake about the use of Butterworth filters. You mention that 2nd order filters are 180 degrees out of phase at the crossover frequency and 2nd order Linkwitz Riley 6db down so that when their electrical polarity is reversed they add up to flat response. But you don’t mention that the phase response of 1st and 2nd order Butterworth crossovers are such that the their low and high pass phase difference at the crossover point is 90 degrees which eliminates the 3db bump in the filters frequency response at their crossover frequency.

Respectfully Submitted,

George S. Louis, Esq., CEO

Digital Systems & Solutions

President of the San Diego Audio Society (SDAS)

Perfect Polarity Pundit Chief Polarity Buster of the Polarity Police

Website: http://www.AudioGeorge.com

Email: AudioGeorge@AudioGeorge.com

Phone: 619-401-9876

George S. Louis says:

Dear Geoff,

I apologize for my penultimate reply wherein I spelled your name “Geof” instead of “Geoff.”

Best regards,

George

George S. Louis says:

Dear Geoff,

FYI: There’s a problem that has been ignored by the entire music industry which I believe is really important to music-lovers that I think you might want to investigate. Approximately 32 years ago when digital media was introduced to the music consuming public as a media with “Perfect Sound Forever” the music industry made a huge screw up when it got the playback polarity of digital music on CDs and later DVD, etc reversed (inverted polarity). On a random basis that means that digital media and files are heard in the wrong polarity approximately 85% of the time and either 92% wrong or correct once their audio and video systems are set to a fixed playback polarity.

The bottom line is that the music played in inverted polarity sounds harsh and two dimensional which is probable the major reason that some music-lovers still believe (without knowing the real reason) that analog music media (that plays in the correct polarity over 99.9999 +% of the time and would also sound bad if played in inverted polarity) sounds better than digital media, when in fact it doesn’t sound as good. That often causes music-lovers to spend untold sums of money and time trying to smooth out the edgy and somewhat irritating and flat sound of digital media. This should be an object lesson on how an entire industry with its experts and electrical engineers can get it wrong and not do anything about if for over 32 years and counting!

But there’s some good news here because in many cases, all one has to do is reverse the connections of all their speakers wires at one end only to correct the mistake that’s free for the doing. For more on how do that, see the homepage of my website: http://www.AudioGeorge.com and scroll down to just below the credit cards I accept. Many in the music industry agree with me. I’m know in the industry as The Perfect Polarity Pundit Chief Polarity Buster of the Polarity Police and come companies send me their digital media/components to check its polarity, and do that pro bono for the sake of the music. I’ve written two monographs that go into great detail about the problem at: http://www.ThePolarityList.com, http://www.AbsolutePolarity.com, and http://www.PolarityGeorge.com.

Respectfully submitted,

George S. Louis, Esq., CEO

Digital Systems & Solutions

President San Diego Audio Society (SDAS)

Website: http://www.AudoGeorge.com

Phone: 619-401-9876

1573 Kimberly Woods Dr.

El Cajon, CA 92020-7261

geoff says:

No problem. This is certainly not the worst mis-spelling of my name that I’ve seen. (That would be either “Goof” or “Greg”…) ;-)

Cheers

-g

geoff says:

Hi again George,

I’m afraid that we’ll have to agree to disagree on some (or possibly, most) of the statements that you make in the comment regarding the audibility of polarity of signals…

It may be that, for a particular playback system with significant asymmetrical distortion issues AND (not OR) a particular moment in a particular recording, the polarity of the playback system will have an audible effect that you talk about in your web posting. However, I’m afraid that such an effect cannot be generalised to the extent of digital recordings vs. analogue ones – or from one loudspeaker to another…

Cheers

-geoff

geoff says:

Hi again George,

Thanks for the comment regarding Butterworth crossovers. You are correct with respect to 1st-order Butterworth crossovers, which I do not mention in this “article” – however, I’m afraid that you are incorrect in the case of 2nd-order Butterworth crossovers, whose filters are 180º apart (which are covered, above). A 3rd-order Butterworth crossover (also covered above) has 270º between the HP and LP sections, and behave as you describe. Perhaps you meant “1st and 3rd order Butterworth” instead of “1st and 2nd order Butterworth” in your comment?

Cheers

-geoff

Tom Barber says:

All very, very interesting. A couple of thoughts … Single-driver dipole speakers (e.g., electrostatics) seem to have a special accuracy of some sort, in spite of the coloration by room reflections. Good headphones similarly have a special accuracy that isn’t ordinarily encountered in speakers. The headphone advantage is possibly explained by the lack of room coloration, or the lack of time smear caused by the room reflections. But, it may also be that in the case of both headphones and single-driver dipole speakers, the superior sound that many people perceive, that may be the explanation for why so many people are particularly fond of headphones or single-driver dipole speakers is the fidelity in the impulse response. I can’t say with any certainty, but I think it is an interesting possibility. Back in the early seventies I was fond of a particular brand/model of speaker, and this was years before I had any real technical knowledge of anything, I sensed that what distinguished this particular speaker was its ability to faithfully reproduce the sound of a whip cracking, which difference I believed I was hearing in ordinary percussion instruments and even non-percussion instruments. Several years later I was casually discussing this with a professor of electronics and amateur speaker builder, and he enlightened me as to the time domain business. It made perfect sense to me at the time, but today I am less certain whether this is the true explanation for why I liked that speaker so much.

One thought about L-R crossovers, which are claimed to sum flat at the crossover point in spite of the fact that radiated power is -3db at the crossover point (1/4 + 1/4 does not equal 1). I have encountered this claim literally dozens of times, on different web sites, but have encountered only one web site that bothered to explain that the reason this happens (ostensibly) is that directivity is increased at the crossover point owing to the use of two drivers. This mentality also seems to be intertwined with the popular notion that the power response has no meaningful connection with the on-axis response and that, more bizarrely still, a flat on-axis response is analytically linked to a flat summed voltage for both drivers. The ostensible explanation encountered nearly universally, for why L-R sums flat while Butterworth yields +3db bump, discusses only summation in consideration of phase, i.e., Butterworth sums to +3db because the two drivers are in phase. Arrrgh. As if, when you add 1/2 and 1/2, you get 3/2 as a consequence of the lack of phase cancellation. Phase cancellation yields attenuation of the two acoustic signals when they are combined, but the lack of phase cancellation cannot possibly cause the sum of two identical and coherent signals to add up to more than twice the value of either of them individually. The only way this is possible is by way of changes in directivity, and as such. And yet, practically all would-be explanations of the supposed flat response of L-R allude to phase summation and make not a peep about the change in directivity. When a big woofer is crossed to a mid-woofer, is the increase in directivity the same as it is for when a mid-tweeter is crossed to a tiny tweeter? I honestly do not know the answer, but my gut tells me that the extent of the increase in directivity depends on the size of the drivers relative to the wavelength at the crossover point. I suspect that this effect does not occur at all when the two drivers are both very small in relation to this wavelength, the reason being that directivity and dispersion at 100 Hz are pretty much the same for a 15″ driver as for an 8″ driver. In both cases, the wavelength is sufficiently greater than the driver diameter for the effect to be in essence that of a point source.

theodore paschos says:

Hi i have read all of your articles with great interest.

Where is the 2nd part of the article ”It’s impossible to build a good loudspeaker”;

Is it still in progress;

Theodore Paschos

Greece

geoff says:

Hi Theodore,

Sorry… I haven’t even started working on Part 2… It doesn’t exist yet…

Cheers

-geoff

MYKAL FURY says:

Hi Geoff,

Enjoyed your crossover write up.

Let me start by stating:

As a veteran Recording Artist/Vox

& Singer/Songwriter with over 70

songs published & as many Albums

released over the past 25 years.

Geoff, you can imagine I’ve been subjected

to just about every type of studio monitor, PA speaker,

stage monitor and the most important transducers

of all…

the “beloved” home Hi-Fi speaker (Towers, Bookshelves & Sats).

I say most important of al, because we’d do a final fly by

of the audio masters over a pair of “standard” consumer based

Hi-Fi speakers (Not your TAD’s, Logans or KEFs).

These final fly bys over the home speakers would give us an idea

of how the audio master will realistically play back in the

consumer’s home.

Moreover, we’d make test cassettes & cd’s to play in the family car

as well.

This would all be a test in futility unless the playbacks were done in

homes & cars by listeners who were well acquainted with the sweetspot

in their home & car.

Now, these home & car speakers weren’t equal where crossovers

were concerned.

And yet, with the fly bys in comparison with the studio monitors,

we managed to come up with a final studio master

that split the difference, yet, retained the sonic,3D magic, that was present

in mission control playback sessions.

This continuity, was achieved by using the fly by technique

I posted above.

I stated these studio secrets (which you no doubt, already know) to show

that the crossovers in each speaker (some cheapies had no crossovers)

in the fly by mastering playbacks differed, yet we still maintained the

3D sound field we mixed and mastered in mission control.

Good sound is good sound & the “final” output is what the consumer

should be concerned with, not white paper mathematics (I say respectively).

I hope my post here is received in the positive spirit it’s written in?

Metal !

Anonymous says:

*Use digital filtering.

geoff says:

Hi,

All of the filters in the crossover strategies that I’ve presented here can be implemented as digital filters. However, the effect of the filtering strategy on the directivity will not be different.

Of course, a loudspeaker’s directivity can be designed using multiple drivers and a frequency-dependent phase/delay control over each driver. However, that’s outside the scope of this posting.

Cheers

-geoff